The 2010 Edition of NFPA 72 and Its Implications for the AV Industry

advertisement

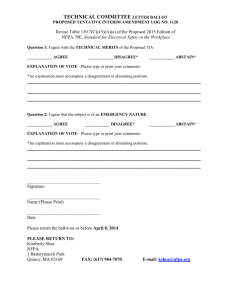

InfoComm Whitepaper: The 2010 Edition of NFPA 72 and Its Implications for the AV Industry Executive Summary Building codes have existed for almost 4,000 years. To this day, building and safety codes dictate construction practices. But codes have only become high priority for AV professionals over the last 50 years, as AV equipment migrated from the movable rolling cart to permanent installation in public and private buildings. Fire detection and prevention also has a long history. But the intersection of building codes with fire detection and AV equipment is a much more recent trend. For years, fire alarm notification was limited to bells, horns and telegraph messages. Only in the latter half of the 20th century have we seen the use of visible notification devices and commercial loudspeakers in fire-alarm notification systems. Even then, these devices have been primarily special-purpose devices such as strobe lights and low-fidelity (but very loud) loudspeakers or combination devices. The requirements for use of these devices, along with all other elements of a fire alarm system, were assembled in a collection of documents which eventually became the National Fire Alarm Code (or NFPA 72), first published by the National Fire Protection Association in 1993. But it wasn’t until the most recent revision of NFPA 72 that code-compliant commercial/professional-grade audio systems and video displays were recognized as legitimate components of an emergency communications system. The 2010 edition of NFPA 72 has been called the most significant revision of the National Fire Alarm Code since its creation. Among the changes in the 2010 edition is a new emphasis on the design, installation and performance characteristics of audio and video components and systems. Many areas of expertise we normally associate with audiovisual professionals are now clearly linked with the lifesafety and construction industries. (NOTE: NFPA 72 applies primarily to work in the United States. European standard EN54 governs similar fire-alarm and warning systems in Europe. The Professional Audio Manufacturers Alliance (PAMA) will compare NFPA 72 and EN54 in a future white paper.) Adoption of the revised NFPA 72 code is still in the very early stages. The “inter-industry” exposure that this code revision represents will likely result in increased opportunities for AV professionals. Taking advantage of such opportunities requires knowledge of the relevant revisions. This InfoComm International® white paper reviews the important new changes to NFPA 72 as a result of the 2010 revision, and the potential implications for the AV communications industry. InfoComm White Paper: NFPA 72-2010 and Its Implications for the AV Industry 1 I. Introduction Commercial AV systems perform many critical functions, from delivering education and information, to entertaining audiences. But none of these functions is more important than AV systems’ role in saving lives. While the life-saving capability of many AV systems has been recognized by AV professionals for decades, it has only been in the last decade that government agencies and code-making authorities have realized that audio and visual technologies can – and should – be considered essential elements in systems designed specifically for emergency situations. The history of code establishment goes back more than 100 years. In the middle of the 19th century, as electricity in homes and businesses became more common, the link between electricity and fire was obvious and it was clear that society needed safety codes. The communications technology available at the time allowed only alerting capabilities, and information was conveyed by telegraph. In 1896, the National Fire Protection Agency (NFPA) was established in the United States to reduce the worldwide burden of fire and other hazards by providing and advocating consensus codes and standards, research, training and education. The first national code was established in 1897 and dubbed the National Electrical Code (NEC), focused on electrical safety for the purpose of fire prevention. Despite its “national” title, it was developed with international input. New and related codes from Germany and the United Kingdom were referenced during the development of the code. In the early 1900s, members from the U.K., Australia and Russia joined the NFPA, followed soon after by representation from other nations. Today, the NFPA publishes 300 codes and standards designed to minimize the risk and effects of fire by establishing criteria for building, processing, design, service and installation of systems in the United States and other countries. Many AV professionals are already familiar with the National Electrical Code, also known as NFPA 70. It provides minimum standards and guidelines for the installation of electrical conductors, equipment and raceways; signaling and communications conductors, equipment and raceways; and optical fiber cables and raceways. Today, NFPA 70 is used throughout the world. The National Fire Alarm and Signaling Code, better known as NFPA 72, has a much more complicated history. Its predecessors include signaling standards that date back to 1898 and 1905, respectively. NFPA 72 was first published in 1993 as the National Fire Alarm Code, a consolidation of at least six individual standards documents. One of the collected standards, NFPA 72F, was first published in 1985 and defined the installation, maintenance and use of emergency/voice alarm communications systems (EVACS). At the time of that standard’s publication — and for 25 years after — EVACS had to be dedicated voice communications systems for use only in the event of a fire incident. Because most fire-alarm systems were (and continue to be) designed and installed by fire-alarm specialists, these single-purpose voice InfoComm White Paper: NFPA 72-2010 and Its Implications for the AV Industry 2 systems tended to be modeled on typical non-voice, auditory notification systems, which used horns or bells. Sound quality was not a design factor; the word “intelligible” did not appear in NFPA 72 until 1999. As its title implied, the original NFPA 72 focused on fire-alarm systems. However, subsequent revisions have started to reflect the realization that fire, while still a danger, is not the only hazard to which building occupants must be alerted. And that regardless of the present danger, occupants need additional information in order to react appropriately. (NOTE: NFPA 72 applies primarily to work in the United States. European standard EN54 governs similar fire-alarm and warning systems in Europe. PAMA will compare NFPA 72 and EN54 in a future white paper.) NFPA 72 was revised in 1996, 1999, 2002 and 2007. It was the 2002 revision, following the September 11, 2001, attacks, that included major new sections on various technical matters, including power supply requirements; a new requirement addressing impairments to fire-alarm systems; additional requirements concerning the review and approval of performance-based detection system designs; revision of the rules for system survivability from attack by fire; the introduction of rules for an alternate approach for audible signaling; and the addition of requirements to address performance-based designs for visible signaling. A significant addition to the 2007 revision introduced mass notification systems (MNS) as an Annex1 to the code document. The MNS concept was developed by the U.S. military after events such as the 1996 bombing of Khobar Towers in Saudi Arabia. A 2002 Defense Department document UFC 4-021-01 Design and O&M: Mass Notification Systems described “the capability to provide real-time information to all building occupants or personnel in the immediate vicinity of a building during emergency situations.” As early as 2003, the U.S. Air Force Civil Engineering Support Agency petitioned NFPA to develop a standard for mass notification. And an April 2008 revision of DoD UFC 4-021-01 expanded the definition of MNS as a way to provide “real-time information and instructions to people in a building, area, site, or installation using intelligible voice communications along with visible signals, text, and graphics, and possibly including tactile or other communication methods [emphasis added].” This definition recognizes the requirement of achieving a specific quality level of audio communication, as well as the need to communicate by means beyond auditory only. Though promoted by the military, mass notification systems apply to a variety of buildings, from offices to schools, as tragedies such as the September 11 attacks and school shootings at Columbine High School and Virginia Tech University demonstrated. Both MNS and EVACS are now considered part of an overall emergency communications system (ECS), as described in a new section of NFPA 72. The 2010 revision of NFPA 72 was approved by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) on August 26, 2009. In its current form, NFPA 72 covers the application, installation, location, performance, 1 Information in an “Annex” is provided for informational purposes only. An Annex is not a part of the requirements of an NFPA standard. Information is presented as actions or steps which “should” be taken – as opposed to mandatory requirements that “shall” be done. InfoComm White Paper: NFPA 72-2010 and Its Implications for the AV Industry 3 inspection, testing and maintenance of fire alarm systems, supervising station alarm systems, public emergency alarm reporting systems, fire warning equipment and ECS, along with their components. Its purpose is to establish minimum required levels of performance, but not the only methods by which these requirements are to be achieved. However, if adopted by a local authority having jurisdiction (AHJ), NFPA 72 requirements must be met or surpassed in order to pass inspection and acquire certificates of occupancy. II. A Look Inside 2010 NFPA 72 The 2010 revision of NFPA 72 includes some of the most significant and extensive changes since the Code was first published in 1993. The 2007 version was 272 pages in 11 chapters; the 2010 version is 361 pages in 29 chapters (15 of which are reserved for future expansion). The changes reflect experience gained from incidents over the last several decades that have made it clear that, although fire disasters remain an omnipresent risk, there are other events that can cause suffering and loss of life. New language and topics covered in NFPA 72 also indicate a reevaluation of how responders should interpret and react to any emergency. The first and most obvious change to the 2010 revision of NFPA 72 is its title, which indicates the broader subject matter addressed by the Code. The new National Fire Alarm and Signaling Code encompasses non-fire alarm-related capabilities, such as mass notification, carbon monoxide and other gas detection, as well as other life-saving measures. Warning systems must do much more than just trigger an alarm in the event of fire. They must signal other types of events and, more importantly, convey what actions should be taken. Although the term “signaling” has been part of code language almost since the beginning, its inclusion in the new document title emphasizes the need to communicate specific information. It is in this communication where the expertise of AV professionals may be brought to bear. Chapter 24 and the AV Professional Of all the new content in the 2010 revision of NFPA 72, the two most relevant sections for AV professionals are Chapter 24, “Emergency Communications Systems,” and Annex D, “Speech Intelligibility.” Much of the material for the new ECS chapter was included as Annex E in the 2007 edition, which focused primarily on MNS. However, because it was included in an Annex and not in the body of the Code, adoption of the 2007 NFPA 72 did not require conformity with any of the practices as written. Now that MNS and other types of ECS are included as a chapter within the Code, adoption of the 2010 edition will ensure that these requirements are more broadly implemented. Chapter 24, according to the document, “establishes minimum required levels of performance, reliability and quality of installation for emergency communications systems but does not establish the only methods by which these requirements are to be achieved.” InfoComm White Paper: NFPA 72-2010 and Its Implications for the AV Industry 4 Two important concepts in this description are the ideas of “minimum required levels” and the fact that the Code allows a variety of methods for satisfying the requirements. For people working with NFPA 72, these distinctions are important because they imply that the requirements provide only a baseline of acceptable performance. Facilities owners or an AHJ may, at their discretion, expect systems to perform above and beyond the requirements in Chapter 24. Also, the design methodology used to achieve the required performance allows room for interpretation and, thus, for alternative and competitive approaches. Perhaps the clearest indication that the 2010 revision has moved beyond fire-related emergencies is the Chapter 24 statement, “An emergency communications system is intended to communicate information about emergencies including, but not limited to, fire, human-caused events (accidental and intentional), other dangerous situations, accidents, and natural disasters.” With such a wide range of potential events, it’s clear that more sophisticated communications technology is required to meet the Code’s goals. Moreover, Chapter 24 of the latest NFPA 72 redefines message priority. For the first time, a local MNS has the authority to override fire alarm systems with voice messages. According to the code, “When identified by the risk analysis and emergency response plan, messages from the mass notification system shall take priority over fire alarm messages and signals.” This, too, is an indication of the growing importance of communications systems, other than fire alarms, that AV professionals are expert in deploying. The remainder of Chapter 24, along with Chapter 18 (“Notification Appliances”) and Annex D (“Speech Intelligibility”), provides more detail on what emergency communications systems might include and how they should perform. Development of an Emergency Communications System Chapter 24 of the 2010 NFPA 72 includes specific information about how an ECS must be designed, stating that “each application of a mass notification system shall be specific to the nature and anticipated risks of each facility for which it is designed.” In order to identify those risks, an analysis is required. A risk analysis is a formalized process “to characterize the likelihood, vulnerability, and magnitude of incidents associated with natural, technological, and manmade disasters and other emergencies that address scenarios of concern, their probability, and their potential consequences.” The risk analysis is intended to force response planners and system designers to anticipate and define the circumstances under which a mass notification signal “shall” have the ability to override the fire alarm evacuation signals, in order to redirect building occupants based on the condition or event. This is important because, for the first time, the Code implies that auditory and visual signaling – and the systems that convey them – should be considered a high priority. InfoComm White Paper: NFPA 72-2010 and Its Implications for the AV Industry 5 From the risk analysis, an emergency response plan is developed, which is a documented set of actions that address a response to potential events2. It also identifies responsible personnel, procedures, equipment and operations, and the appropriate training to ensure that these procedures are properly followed in an actual event. Two classifications of emergency communications systems are defined in Chapter 24: one-way and twoway. Source: National Fire Alarm and Signaling Code, 2010 Edition, Annex A One-Way Emergency Communications Systems One-way emergency communications systems are intended to broadcast information in emergency situations to people in one or more specified indoor or outdoor areas. These communications systems can be either auditory, visual or both. Before this revision, fire-alarm systems had generally been allowed to provide only occupant notification of fire events. This change to include notification of more than just people in building casts one-way emergency communications in a much broader light to include building systems, wide-area notification (typically outdoors) and distributed notification. Oneway systems are further subdivided into four types: 1. 2. 3. 4. In-building fire emergency voice/alarm communications systems In-building mass notification systems Wide-area mass notification systems Distributed recipient mass notification systems (DRMNS) 2 Emergency Response Plans are defined in the documents, NFPA 1600, Standard on Disaster/Emergency Management and Business Continuity Programs, and NFPA 1620, Recommended Practice for Pre-Incident Planning. InfoComm White Paper: NFPA 72-2010 and Its Implications for the AV Industry 6 In-building EVACS In-building fire EVACS can produce voice evacuation messages, either pre-recorded or live. Requirements for pre-recorded messages are found in Chapter 23, “Protected Premises Fire Alarm Systems (23.10). “ In-building MNS In-building mass notification systems are further broken down into the following categories: 1. Combination ECS, using a single point of control, or a combination of control systems, to control various emergency communications systems such as fire alarm, mass notification, fire fighter communications, area of refuge communications, elevator communications or others. 2. Interfaces with MNS, in which the MNS is allowed to provide air-handling control, door control, elevator controls and control of other building systems as determined by the risk analysis permitted by the AHJ. Also, individual building mass notification systems are allowed to interface with a wide-area MNS, but not necessarily be controlled by the wide-area MNS. 3. PA systems used for ECS. If deemed suitable by the ECS designer, a public address system can be used for mass notification. Some of the requirements include the ability to allow emergency messages to take priority over non-emergency messages, automatic volume default to a pre-set emergency sound level, zoning capabilities and interfacing with visible notification devices where required. When it comes to AV equipment manufacturers, Chapter 24 states that components “shall be installed, tested, and maintained in accordance with the manufacturer’s published instructions and this Code”. Implicit in this directive is that responsibility – and presumably liability – for proper installation and operation of equipment is shared by the manufacturer. This underscores the critical importance of the design and documentation of commercial AV components for product safety and reliability, as well as the need for a thorough understanding of codes such as NFPA 72. Wide-area MNS Wide-area mass notification systems refer to systems for outdoor areas, which could interface with other notification systems. Wide-area MNS include campus-wide voice systems, military base public address systems, civil defense warning systems and large outdoor visible displays. Typically, an audio-based wide-area MNS will use high-power speaker arrays (HPSA), which are designed for outdoor use and feature tightly controlled directional characteristics and extremely high SPL capability. The Code includes requirements for mounting HPSAs in order to avoid the possibility of causing hearing damage to nearby individuals. HPSA loudspeakers and exposed electronics enclosures are also required to be tamper-proof and conform to National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) 4 or 4X standards to ensure reliable operation in environmental extremes such as heat, cold, dust, wind and vibration. According to Chapter 24, installed HPSAs and their supporting structures should be designed to withstand a minimum wind speed of 100 miles/hr (161 km/hr, or 86.8 knots). InfoComm White Paper: NFPA 72-2010 and Its Implications for the AV Industry 7 Distributed recipient MNS Distributed recipient mass notification systems (DRMNS) communicate directly to targeted individuals and groups that might not be in a contiguous area. These systems are not to be used in place of required audible and visible alerting mass notification systems, but shall be integrated with mass notification systems whenever possible. Two-Way In-Building Emergency Communications Systems Two-way systems include systems that are likely to be used by building occupants, and systems that are to be used only by emergency services personnel. Two-way emergency communications systems are used both to exchange information and to communicate information, such as instructions, acknowledgement of receipt of messages, condition of local environment and condition of persons, and to inform that help is on its way. NFPA 72 covers wired and non-wired (radio or wireless) emergency services communications, “area of refuge”3 (areas of rescue assistance) communications and elevator ECS. Other ECS Topics Other sections in Chapter 24 that might apply to AV professionals cover systems for Information, Command, and Control (24.6), and the requirements for performance-based design (24.7). As the name implies, Information, Command, and Control systems refers to systems used to receive and transmit information between premises sources or premises systems and the central control station(s). “Performance-based design” is a relatively new concept in facility design that gives design teams the flexibility to maintain safety while using progressive design concepts that might otherwise have been restricted by stringent enforcement of building code requirements. A performance-based design is dependent on the findings of the risk analysis and must demonstrate that design alternative complies with applicable codes. Annex D and Speech Intelligibility Regardless of type, Chapter 24 clearly states that all emergency communications systems are required to be capable of producing messages “with voice intelligibility,” defined as “the quality or condition of being intelligible.” (The term “intelligible” is further defined as “capable of being understood; comprehensible; clear.”) That said, a precise and quantifiable definition of voice intelligibility is missing from the body of the code. Suggestions for what makes an intelligible ECS are included in Annex D, which is therefore required reading for AV professionals working on ECS installations. Intelligibility was first introduced to NFPA 72 in a 1999 appendix, requiring a measurement of 0.70 on the Common Intelligibility Scale (CIS), one widely accepted industry measure of intelligibility. This threshold persists in the 2010 Annex D, which states that “the intelligibility of an emergency communication system is considered acceptable if at least 90 percent of the measurement locations 3 An “area of refuge” or “area of rescue assistance” is an area that has direct access to an exit, where people who are unable to use stairs can remain temporarily in safety to await further instructions or assistance during emergency evacuation or other emergency situation. InfoComm White Paper: NFPA 72-2010 and Its Implications for the AV Industry 8 within each ADS4 [acoustically distinguishable space] have a measured [Speech Transmission Index] of not less than 0.45 (0.65 CIS) and an average STI of not less than 0.50 STI (0.70 CIS).”5 Most audio professionals will recognize that a CIS rating of 0.70 is far from perfect intelligibility – it corresponds to approximately 80-percent word intelligibility and about 95-percent sentence intelligibility. Although such a rating is slightly higher than what is required to accurately transmit an emergency message, it would be considered by audio professionals to be barely acceptable for a sound system designed for non-emergency messaging. Because it is not in the actual body of the Code, Annex D is meant only as guidance on the planning, design, installation and testing of voice communications systems. It is not intended to instruct how to interpret test results or to correct for poor speech intelligibility. Still, Annex D mentions several methods for measuring speech intelligibility — both quantitative and subject-based methods. Although there are at least three common quantitative methods6 in use in the pro audio industry, the Speech Transmission Index (STI) is the one listed in Annex D of NFPA 72, using the STI for Public Address (STI-PA) test signal. STI-PA was developed over 10 years ago by the Dutch research and certification institute TNO Human Factors. Some of the advantages of STI-PA over the earlier STI or RASTI (Rapid Speech Transmission Index) methods are: 1) The STI-PA method considers the effect of the actual background, 2) it reduces the amount of time it takes to make a measurement, 3) measurements can be done using a portable, hand-held tool, 4) it works well with sound systems with moderate non-linear response or limited bandwidth, and 5) it uses a higher degree of modulation for each test frequency than the RASTI method, so it is less susceptible to error caused by interference from non-stationary background noise. The STI-PA test signal has been standardized in IEC 60268, Sound System Equipment 7. Several qualitative, subject-based methods are also included in Annex D, including the Phonetically Balanced word test (PB), Modified Rhyme Test (MRT), and the Speech Intelligibility Index (SII) method. These methods are generally used only in academic research because they are not practical or expedient as on-site measurement techniques. Finally, it is worth noting that intelligibility is not required for every space in a building. Determining intelligibility requirements happens during the risk analysis and emergency planning stages. The need for intelligibility is considered within each ADS on an individual basis, however Chapter 24 of the code states that intelligibility is not required in the following areas, unless the AHJ requires it: 4 An ADS is defined as “an emergency communication system notification zone, or subdivision thereof, that might be an enclosed or otherwise physically defined space, or that may be distinguished from other spaces because of different acoustical, environmental or use characteristics such as reverberation time and ambient sound pressure level.” 5 Annex D.2.4, NFPA 72-2010. 6 Other methods include Speech Intelligibility Index (SII – formerly Articulation Index), and Articulation Loss of Consonants (%Alcons). 7 IEC 60268-16, “Sound system equipment — Part 16: Objective rating of speech intelligibility by speech transmission index”, International Electrotechnical Commission, Geneva, Switzerland, May 22, 2003. InfoComm White Paper: NFPA 72-2010 and Its Implications for the AV Industry 9 1. Private bathrooms, shower rooms, saunas and similar rooms/areas 2. Mechanical/electrical/elevator equipment rooms 3. Elevator cars 4. Individual offices 5. Kitchens 6. Storage rooms and closets 8. Rooms/areas where intelligibility cannot reasonably be predicted III. What it All Means for Pro AV The new sections and revisions to NFPA 72-2010, especially as compared to earlier versions, represent a major milestone in the evolution of the commercial AV industry. Chapter 24 and the new Annex D on speech intelligibility specifically elevate the role of the AV systems consultant, designer, and installer in the building design and commissioning process. Because of their expertise in audiovisual communications, AV professionals have an opportunity to work with other trades to ensure buildings meet NFPA 72-2010 requirements as they are implemented. Moreover, there are now potential legal reasons why AV professionals should be included in building design and construction, especially in relation to emergency communications systems. Once the new code is referenced in the International Building Code, and adopted by an AHJ, meeting the requirements will be mandated by law. While the latest revisions to NFPA 72 highlight the importance of AV systems in the construction and life safety industries, this new spotlight on AV may actually result in creating a threat to companies whose livelihood depends on the installation of such systems in commercial spaces. For more than 30 years, the sound contracting and AV systems integration industries have struggled to establish an identity outside the purview of the electrical contracting industry. Often, sound contracting is identified generically with low voltage systems, creating overlap with security, fire alarm, and other specialized low voltage systems. Over the years, some companies have succeeded in offering all of these systems to commercial and residential customers. Recent articles in trade publications in the physical security, cabling, construction and electrical contracting industries have also discussed the changes in NFPA 72-2010. The inclusion of details such as loudspeaker and video display installation, font sizing for legibility, and speech intelligibility brings muchneeded definition to these important attributes of AV systems. But what remains to be seen is whether such widespread information will be taken for comprehensive guidelines that could lead professionals outside the AV industry to attempt to implement systems that fall outside their usual expertise. On the other hand, a discussion of the special characteristics of professionally designed and installed AV systems in critical life-safety applications could lead to more partnering for AV professionals with other building trades. The new Chapter 24 on emergency communications systems and Annex D on intelligibility are likely to help validate the expertise of AV professionals in the eyes of their construction industry peers. InfoComm White Paper: NFPA 72-2010 and Its Implications for the AV Industry 10 More than anything, the new visibility and recognition of AV mean that all parties must realize there cannot be one single expert in all areas of emergency communications. Most AV systems are already the result of a systems integration approach. With the 2010 revision, the concept of systems integration takes on even deeper meaning. The interoperability of AV systems with security, power, HVAC, IT and other building infrastructure system will require an even higher level of complexity and knowledge. It is unlikely that any one building trade can successfully master all necessary areas, so teamwork will be critical. IV. Pro AV Standards and NFPA 72 Although the significance of the new Chapter 24 and Annex D should not be understated, AV professionals who study the new Code will recognize that it is still missing information pertaining to the auditory and visual communications experience. For example, most of the detail regarding visual notification devices centers on installation location, image brightness and text legibility. Little attention is paid to other common AV design factors such as viewing distance, the use of video displays as notification devices and related performance factors such as contrast ratio. Digital signage and scrolling ticker-text-based systems are proliferating, especially on education campuses, yet there is little recognition of this in the Code. On the audio side, the 2010 revision covers the topic of speech intelligibility in some detail, but provides little guidance on other areas affecting the quality of auditory communication. Basic guidelines for audibility, coverage and dealing with ambient noise are included, but critical detail is lacking. Also, there is no discussion of room acoustics, which is an inherent factor in the perception of sound in any enclosed environment. A first step toward including more AV-specific topics in any code language is to develop performance standards that are recognized by standards organizations. InfoComm International® is working to create such standards. InfoComm’s most recent standard, ANSI/INFOCOMM 3M-2011: Projected Image System Contrast Ratio, defines projected image system contrast ratio and its measurement for both permanently installed systems and live events. It defines four minimum contrast ratios based on content viewing requirements and provides the tools that AV designers and integrators can use to ensure optimal viewing. In addition, InfoComm is developing a suite of audio standards for submission to ANSI, the sum of which could significantly affect and enhance systems designed to help meet NFPA 72 requirements. The first standard, ANSI/INFOCOMM 1M-2009 Audio Coverage Uniformity in Enclosed Listener Areas, was accepted and released in 2009. One of the fundamental goals of sound system performance for both speech reinforcement and program audio is the delivery of uniform coverage in the listening area. A well-executed audio system design is one that allows all listeners to hear the system at approximately the same sound pressure level throughout the desired frequency spectrum range, no matter where positioned in the designated listening area. The Audio Coverage Uniformity in Enclosed Listener Areas InfoComm White Paper: NFPA 72-2010 and Its Implications for the AV Industry 11 standard provides a characterization of and a procedure to measure this spatial coverage, with criteria for use in the design and commissioning of audio systems. To round out the audio suite, there will be four new standards, driven by four separate task groups. These four new standards, combined with ANSI/INFOCOMM 1M-2009 and an ambient noise measurement standard, such as noise criteria (NC), will constitute a comprehensive characterization of a sound system. Together, the Amplified Audio System Performance Standards Suite will define performance requirements for an amplified audio system in an enclosed area. Conformance to the parameters defined in all the InfoComm standards will, for the first time, make it possible — and in a measureable, repeatable way — to ensure that a sound system will provide high quality, intelligibility and fidelity. A summary of the standards in development: Equalization Optimization Audio system equalization best practices have been established by a variety of references and have been available to the industry for a number of years. This standard will describe the performance requirements for audio system equalization for a variety of venues within enclosed areas and provide a method for achieving an equalization of an amplified audio system to optimize the resulting performance in the room environment. Note that this standard will apply to both music reproduction systems, which require a full frequency spectrum, and speech reinforcement and/or emergency notification systems, which have a more limited frequency range. Undesirable Sound Audio system performance is negatively impacted when unwanted sound elements are generated within and caused by the system. These elements include: 1) electronic noise introduced by elements of the system electronics, often called hum or distortion, and other unwanted electronic artifacts; and 2) acoustical noise, such as noise from the vibration of a system’s components. This standard will set an acceptable threshold for unwanted sound elements in amplified audio systems; describe the method for testing the amplified audio system; and provide the method of documentation to demonstrate that the unwanted sounds are not evident while the system is operating. The standard would describe the measurement of the audio signal as compared to the noise level of the system. This standard is not InfoComm White Paper: NFPA 72-2010 and Its Implications for the AV Industry 12 intended to measure the acoustics of a space, nor is it intended to compare the performance of the system to the environment. Reproduced Speech and Reproduced Music Quality This standard proposes to address the minimum acceptable levels of speech quality and reproduced music performance quality for amplified audio systems from the perspective of time-domain acoustical parameters. The standard should incorporate currently accepted methods for acoustical measurement of the system to determine minimal acceptable levels of sound clarity/quality for speech and performance reproduction quality for music. Sound Pressure Level Optimization in Audiovisual Systems The nominal audio signal level in an audiovisual system is referenced to the level of ambient acoustic noise in the venue. This standard would characterize this ambient noise, recommend a signal-to-noise ratio for different venue types, and provide measurement techniques using common test equipment. The standard may also refer to maximum sound pressure levels acceptable for audience safety. All of these areas affect the quality of perceived sound and therefore can impact the accuracy of information conveyed by audio and video systems. As these InfoComm standards and others are developed and gain acceptance by ANSI and other organizations, the effectiveness of communications systems in helping to manage emergency situations and save lives could be enhanced by including them in future revisions of NFPA 72. InfoComm White Paper: NFPA 72-2010 and Its Implications for the AV Industry 13 V. Conclusion Studying and interpreting NFPA 72-2010, like the analysis of many codes or legal documents, is a bit like finding one’s way through a labyrinth. Cross references, abrupt changes in direction and ambiguous language can lead one either toward greater understanding or false assumptions. It should be understood by AV professionals that NFPA 72 is not a “law”; it does not technically mandate the installation of fire alarms, emergency communication or any other types of system. The Code only provides requirements for the installation, performance, testing, inspection and maintenance of these systems, in the event that the AHJ requires conformity. Other codes, such as the International Building Code or NFPA 101 Life Safety Code, determine whether these systems are actually required in the first place. It is the responsibility of the AHJ to enforce the requirements of the Code. A system is only approved once is it is deemed acceptable to the AHJ, and that can depend on which version of a particular Code they have chosen to adopt. It often takes years for the most recent version of a Code to be adopted by a municipality. To date, the states of California, New Jersey, Louisiana and Vermont have adopted the 2010 revision of NFPA. Once the 2012 revision of the International Building Code it completed, it will reference NFPA 72-2010, at which time broader adoption can be expected. It is also important to understand that AHJs and state and local authorities are not required to adopt any code at all. Some will maintain older versions and some may even develop their own local codes. The best course of action in any case is to check with local building authorities before the design of any communications system is begun to determine which codes will be relevant in order to pass inspection. NFPA 72-2010 represents a significant milestone in the development of the commercial/professional AV industry. By incorporating subject matter so closely aligned with the expertise of AV professionals into the code, it simultaneously distinguishes and assimilates the AV industry. Most importantly, NFPA 722010 validates, once and for all, the fact that AV is a legitimate part of the building and construction industries which needs to be considered in order to create functional, efficient, and safe public spaces. InfoComm White Paper: NFPA 72-2010 and Its Implications for the AV Industry 14 VI. Key Terms and Definitions Acoustically distinguishable space (ADS). An emergency communications system notification zone, or subdivision thereof, that might be an enclosed or otherwise physically defined space, or that might be distinguished from other spaces because of different acoustical, environmental, or use characteristics, such as reverberation time and ambient sound pressure level. Authority having jurisdiction (AHJ). A broad term defining, literally, the person who has the authority to enforce a Code. Where public safety is primary, the authority having jurisdiction may be a federal, state, local, or other regional department or individual such as a fire chief; fire marshal; chief of a fire prevention bureau, labor department or health department; building official; electrical inspector; or others having statutory authority. For insurance purposes, an insurance inspection department, rating bureau, or other insurance company representative may be the authority having jurisdiction. In many circumstances, the property owner or his or her designated agent assumes the role of the authority having jurisdiction; at government installations, the commanding officer or departmental official may be the authority having jurisdiction. Code. A standard that is an extensive compilation of provisions covering broad subject matter or that is suitable for adoption into law independently of other codes and standards. The decision to designate a standard as a “code” is based on such factors as the size and scope of the document, its intended use and form of adoption, and whether it contains substantial enforcement and administrative provisions. Emergency communications system (ECS). An auditory or visual system intended to communicate information about emergencies including but not limited to fire, terrorist activities, other dangerous situations, accidents and natural disasters. An ECS provides for the protection of life by indicating the existence of an emergency situation and communicating information necessary to facilitate an appropriate response and action. Mass notification system (MNS). A system used to provide information and instructions to people in building or other spaces using intelligible voice communications and including visible signals, text, graphics, tactile or other communication methods. Notification appliance. A fire alarm system component such as a bell, horn, speaker, light or text display that provides audible, tactile, or visible outputs, or any combination thereof. Standard. According to NFPA definition, a “standard” is a document, the main text of which contains only mandatory provisions using the word "shall" to indicate requirements, and which is in a form generally suitable for mandatory reference by another standard or code or for adoption into law. Nonmandatory provisions are located in an appendix, footnote, or fine-print note and are not to be considered a part of the requirements of a standard. InfoComm White Paper: NFPA 72-2010 and Its Implications for the AV Industry 15 VII. References 1. Fire Alarm Signaling Systems, Fourth Edition, 2010. Richard W. Bukowski, Wayne D. Moore, Morgan Hurley, published by the National Fire Protection Association, Quincy, MA. 2. NFPA 72®, National Fire Alarm Code, 2007 Edition, published by the National Fire Protection Association, Quincy, MA. 3. NFPA 72®, National Fire Alarm and Signaling Code, 2010 Edition, published by the National Fire Protection Association, Quincy, MA. 4. Understanding Speech Intelligibility and the Fire Alarm Code, by Kenneth Jacob, Bose Corporation, presented at the National Fire Protection Association Congress, May 14, 2001. 5. Special thanks to Joe Bocchiaro, Allen Weidman, InfoComm International; Ray Rayburn, K2 Audio LLC; John Murray, Optimum System Solutions; Gary Keith, NFPA. InfoComm White Paper: NFPA 72-2010 and Its Implications for the AV Industry 16