National Fire Protection Association, NFPA 921, Guide for Fire and

advertisement

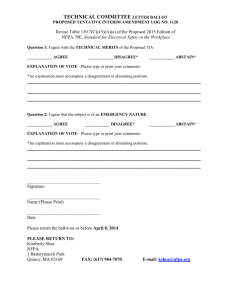

National Fire Protection Association, NFPA 921, Guide for Fire and Explosion Investigations An Update and a Perspective on the 2004 Edition Daniel L. Churchward Kodiak Enterprises, Inc. 6409 Constitution Drive Fort Wayne, Indiana 46804 (260) 432-6590 DChurchward@KodiakConsulting.com Return to Course Book Table of Contents DANIEL CHURCHWARD began his career in 1971 as a police officer with the Allen County, Indiana, Sheriff ’s Department. In 1978, he joined the Adams Township Fire Department in Fort Wayne, Indiana, as a career firefighter. During this time, Mr. Churchward learned the craft of fire investigation and had the opportunity to practice his skills on many hundreds of fire scenes. In 1981, he began to perform fire origin and cause investigations with Barker and Herbert Analytical Laboratories in New Haven, Indiana. He graduated from Purdue University with a B.S. Electrical Engineering Technology in 1988 and assumed the position of engineering laboratory manager with Barker Labs. In 1991, Royal Insurance hired Mr. Churchward into their SIU as their only on-staff engineer. He either investigated or managed their large-loss fire scenes for the Royal and had the opportunity to work many multimillion-dollar fires. In 1995, Mr. Churchward started full time with Kodiak Enterprises, Inc. The company specializes in fire investigation, safety consulting, large-loss site management, and training. Today, Kodiak Enterprises consists of nationally recognized experts in fire investigation technologies and methodologies. Mr. Churchward has qualified as an expert witness in U. S. Federal District Courts and several state jurisdictions. The highlight of his career has been his involvement in the National Fire Protection Association Technical Committee on Fire Investigations. This group has produced the NFPA 921, Guide for Fire and Explosion Investigations. He is a charter member of this committee and currently serves as committee chairman. Kodiak Enterprises, Inc. accepts NFPA 921 as the most significant treatise on fire investigation and as an authoritative source for fire investigation technology and methodology. Mr. Churchward is the chair of the NFPA Technical Committee on Fire Investigations. This paper is a product of his work alone and is not meant to indicate the position, official or otherwise, of the NFPA, the Technical Committee as a group, or any of its members. National Fire Protection Association, NFPA 921, Guide for Fire and Explosion Investigations An Update and a Perspective on the 2004 Edition Table of Contents I. II. III. IV. Background ............................................................................................................................................. 5 NFPA Process ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Highlights of the 2004 Edition ................................................................................................................. 6 Conclusion ............................................................................................................................................... 7 National Fire Protection Association, NFPA 921 ❖ Churchward ❖ 3 National Fire Protection Association, NFPA 921, Guide for Fire and Explosion Investigations An Update and a Perspective on the 2004 Edition I. Background The National Fire Protection Association (“NFPA”) began an effort in 1984 to develop a document that would assist all fire investigators in conducting thorough and scientifically valid fire investigations. The effort began with the formulation of the Technical Committee on Fire Investigations (“TCFI”) in late 1984 and will culminate in the issuance in January 2004 of the 2004 edition of the Guide for Fire and Explosion Investigation. This paper will provide insight into the development of the document and a perspective on the changes that will exist in the new edition. A brief overview of what has transpired in the 19 years leading up to this edition is in order. The TCFI completed the initial edition of this document in late 1991 and the NFPA Standards Council issued the 1992 edition on 17 January 1992. The stated purpose was “…to assist in improving the fire investigation process and the quality of information on fires resulting from the investigative process.” NFPA 921, Guide for Fire and Explosion Investigations, 1992 edition. The TCFI’s position throughout the development process has been to “…provide guidance that is based on accepted scientific principals or scientific research.” In 1994, the TCFI completed work on the 1995 edition of the document and the NFPA Standard’s Council issued it on 13 January 1995. While the 1992 edition contained chapters focusing largely on the determination of origin and cause, the 1995 edition contained several chapters that expanded the document’s purview to vehicle fire investigation, management of major fire investigations, incendiary fires, appliances, and the integration of an existing NFPA document, NFPA 907, Determination of Electrical Fire Causes, 1988 edition. In 1997, the TCFI completed work on the 1998 edition of the document and the NFPA Standard’s Council issued it on 16 January 1998. By this edition, the document had grown to 19 chapters and included a chapter on fuel gas systems in buildings. The fourth edition was completed in 2000 and issued by the NFPA Standards Council on 13 January 2001. This edition has grown substantially from the 1998 edition and includes several new chapters as well as substantial text changes and additions to existing chapters. Throughout the development of the document, the TCFI has kept to the original position: “…based on accepted scientific principals or scientific research.” The success of this document within the fire investigation and legal communities can be directly measured by the accomplishment of this goal. At the time of the presentation of this paper in November 2003 in Phoenix, Arizona, at the DRI Fire and Casualty Seminar, the 2004 edition of NFPA 921 will have been voted upon by the NFPA membership at its fall meeting in Reno. I fully expect to be able to report that this edition has been accepted by the membership and has been passed onto the NFPA Standards Council for their acceptance and issuance in January 2004. II. NFPA Process A brief overview of the “NFPA process” is in order. The NFPA utilizes a process whereby they create their component document, The National Fire Codes. This process is standardized and utilized without exception by all technical committees within the NFPA. Complete information about how the NFPA process works can be gotten at its web site, http://www.nfpa.org. National Fire Protection Association, NFPA 921 ❖ Churchward ❖ 5 Although the process is lengthy in its description, several key points should be made. Membership is not required to participate. You must be a member of record for six months prior to being allowed to vote on the floor of the annual or fall meetings. However, you can participate in all other respects as a nonmember. In all instances, you must follow the rules of the process. The process is standardized and accepted as such by the American National Standards Institute (“ANSI”). Although the forms offered by the NFPA to participate are not required, use of them greatly facilitates your input. The TCFI consists of 30 principal members with several alternates serving as well. All are appointed by the Standards Council with their membership reevaluated every year. Membership is balanced by classifying each member in a special interest group representing such classifications as “manufacturer,”“user,”“enforcing authority,” and “special expert” to name a few. The purpose of this classification system is to insure that no committee is dominated by one interest group. No one group can consist of more than 33 percent of the total membership of the technical committee. The technical committees generally produce proposed documents or changes to existing documents and passage requires a two-thirds vote on the ballot. The scope of NFPA 921 is stated in the first paragraph of the document in the introductory chapter. It states in part that this document is designed to assist individuals who are responsible for investigating and analyzing fire and explosion incidents and rendering opinions related to such incidents. The purpose expands the scope to discuss in greater detail how the document can be used. Included in the purpose discussion are establishing guidelines and recommendations on a systematic investigation and limits that the document may have with specific investigations that may be encountered. Although the document is described as a “guide,” the clear implication to the fire investigation community is that not following the procedures and methodologies offered in NFPA 921 will require justification. Many fire investigators classify NFPA 921 as a “standard of care” in the fire investigation industry. III. Highlights of the 2004 Edition The 2004 edition of NFPA 921 has been developed over the past three years. One major change is that all paragraphs of the document will be numbered in the 2004 edition. This change results from the NFPA’s decision to implement the Manual of Style (“MOS”) throughout the fire codes including those nonmandatory documents such as guides and recommended practices. Further changes resulting from the MOS will be the assignment of chapter 1 as the introduction, the assignment of chapter 2 as the reference chapter, and the assignment of chapter 3 as the definitions chapter. These changes will produce new chapter numbers throughout the remaining document. In addition, another major change in the document is the development of a new chapter and the rewriting of existing chapters. Each will be discussed in turn. All of the chapters are organized into sections of the document. Part I consists of basic information that all fire investigators should know to conduct any fire investigation. These chapters include: administration, reference documents, definitions, methodology, basic fire science and dynamics, fire patterns, building systems, electricity, human behavior, and legal considerations. Part II consists of topics specifically related to fire investigation technology. These chapters include: safety, sources of information, planning, recording the fire scene, evidence, origin and cause determinations and failure analysis. Part III consists of incident specific topics. These chapters include: explosions, incendiary fires, fire & explosion deaths & injuries, appliances, motor vehicle fires, wildfire investigations and management of major investigations. As a consequence of considerable confusion in the fire investigation and legal communities, the TCFI chose to remove the discussion on cause classification from the cause determination chapter and develop it into 6 ❖ Fire and Casualty ❖ November 2003 its own chapter. This new chapter is tentatively named the “Classification of Fire Causes” chapter. The cause determination chapter, as a consequence, was rewritten to accommodate this change. The classification chapter deals with the four traditional classifications that the fire investigation community utilizes: accidental, natural, incendiary, and undetermined. The primary purpose of this new chapter was to inform all that the determination of a fire cause as “undetermined” is different than the determination of a fire’s classification as “undetermined.” Many fire investigations result in the determination of a fire cause, but few fire scenes can reveal sufficient evidence to allow for the determination of the fire’s classification. Determination of the intent of the person(s) involved in the fire cause almost always requires knowledge beyond the traditional origin and cause determination. Further, the trier of fact needs to know that there is a difference between these two concepts so as to understand and judge the relative merits of the testimony of the investigator. The recording the scene chapter was completely rewritten and renamed “Documenting the Investigation.” This chapter was recognized by the TCFI as being a significant chapter and worthy of greater discussion than what had basically been the discussion from the 1992 edition. Although the task group responsible for this chapter initially included considerable verbiage on report writing, the final draft has only a paragraph or two that discusses this important topic. One substantial addition was the acceptance by the TCFI of NFPA 906, Fire Incident Field Notes, into our purview. We updated the note pages from NFPA 906 and put most of them into NFPA 921 as an appendix item. The legal considerations chapter was rewritten as well. The rewrite consisted of basically reorganizing the topics in the existing chapter and updating the discussion on Daubert and Kuhmo. Interestingly enough, there was considerable debate within the TCFI on the need to include any discussion on Daubert or Kuhmo. As was the case in past editions, there were several “hot button” issues that the TCFI had to manage. One proposal submitted to the NFPA consisted of discussion that would have discouraged investigators from offering opinions on fire pattern recognition based solely on the appearance of the patterns. Specifically, the discussion related to investigators stating that certain patterns found in postflashover compartment could only have been caused by “ignitable liquids” without first having laboratory confirmation of the presence of ignitable liquids. This proposal passed nearly unanimously in the report on proposal (“ROP”) but drew considerable opposition in the comment stage. As a consequence of the debate, the TCFI chose to rewrite the proposal, a process that made the discussion even more restrictive. This discussion now does not limit the discussion to postflashover compartments! I anticipate that this issue will be an agenda item for the 2007 edition. Another hot button item was a discussion on “investigator” and “analyst.” In the earliest edition, the TCFI was approached by members from the public sector that voiced their concern that they would be held to a standard of care that far exceeded their capabilities. Specifically, they were saying that they were just “simple fire investigators” and not people who could address all the aspects of fire investigation that NFPA 921 was discussing. To accommodate this concern, the TCFI specified a difference between investigation and analysis. Investigation was defined as “the process of determining the origin, cause, and development of a fire or explosion.” Analysis was defined as “process of determining the origin, cause, development, and responsibility as well as the failure analysis of a fire or explosion.” This distinction has been carried throughout the document since the 1992 edition. The work on the 2004 edition brought a proposal that further discussed the distinction. This time several persons objected to the distinction and successfully stopped the new verbiage from going into the document. No steps were taken to change any of the existing text related to this distinction. IV. Conclusion In conclusion, the 2004 edition of NFPA 921 has been submitted to the NFPA membership for acceptance National Fire Protection Association, NFPA 921 ❖ Churchward ❖ 7 at the fall meeting in Reno, Nevada. Although the results will not be know until after the publication of this paper, I fully expect it to pass and be issued by the Standards Council of the NFPA in January 2004. Several perspectives developed in this last cycle. The number of proposals and comments has dropped from years past. Most of the proposals and comments were much more specific and considerably better thought-out than in past cycles. As a consequence, many more of the proposals and comments were accepted by the TCFI than were accepted in the past cycles. These circumstances suggest several trends. • The document is nearing completion in regards to the development of new chapters. • The fire investigation community is both reading portions of the document and studying it for its content. • The fire investigation community is accepting the document and utilizing it for the common good. • The quality of fire investigations is improving. Although these trends are the opinion of the author and have only the author’s viewpoint to gauge them, their accuracy should become apparent as time passes. NFPA 921 is the only peer-reviewed, consensus document in the fire investigation community. All other texts pale in comparison for technical accuracy. NFPA 921 will continue to lead the way in the fire investigation community in the discussion of technology and methodology as it relates to fire investigation. Return to Course Book Table of Contents 8 ❖ Fire and Casualty ❖ November 2003