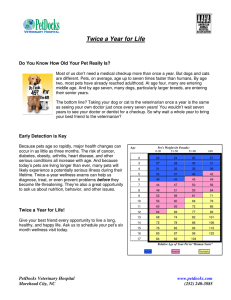

Housing Provider Resource - Practical Guidelines on Pet

advertisement