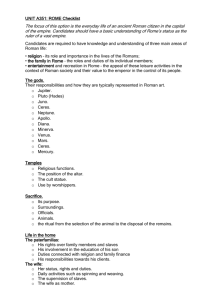

A Study of Roman Society and Its Dependence on slaves.

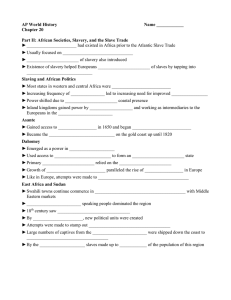

advertisement