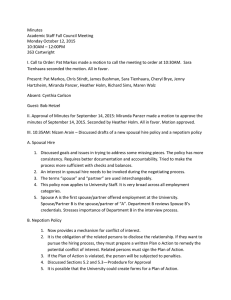

Spousal Support Advisory Guidelines

advertisement