Consideration of What May Influence Student Outcomes on

advertisement

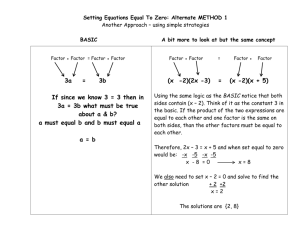

Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 2003, 38(3), 255–270 © Division on Developmental Disabilities Consideration of What May Influence Student Outcomes on Alternate Assessment Diane M. Browder Kathy Fallin UNC Charlotte Charlotte Mecklenburg Schools Stephanie Davis and Meagan Karvonen UNC Charlotte Abstract: Most states recently implemented procedures for alternate assessment for students who cannot participate in state and district-wide assessment programs. The purpose of large-scale assessments is to provide data for evaluation of students’ achievement of state or local standards. Promoting achievement for students who participate in alternate assessment requires both understanding the parameters of the alternate assessment selected by the state or LEA and considering variables related to the student’s individual education. This article describes the variables that may influence alternate assessment outcomes and offers recommendations for how the school team can enhance student achievement. In the last decade, most states have moved toward standards-based educational reform including the use of large-scale accountability systems to measure student performance achievement. The Amendments of IDEA required that students with disabilities be included in national and state assessments. This legislation also required that educators develop and conduct alternate assessments for students who cannot participate in state and district assessments with accommodations. Most states conducted their first alternate assessments during the 2000-01 school year. In Support for this research was provided in part by Grant No. H324M00032 from the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs, awarded to the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. The opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Education, and no official endorsement should be inferred. The authors thank the teachers of the Charlotte Alternate Assessment Model Project for their feedback on these ideas. We also thank Michelle Lorenz for the specific example adapted from her class. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Dr. Diane Browder, Special Education Program, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, 9201 University City Blvd., Charlotte, NC 28223. E-mail: dbrowder@ email.uncc.edu. 2002, No Child Left Behind (NCLB, 2002) required that states measure progress for all students in language arts, math, and science. Alternate assessments provide an option for students with significant cognitive disabilities to demonstrate progress on state standards in these curricular areas. One of the criticisms of high stakes testing is that excellence in teaching, not a proliferation of testing, produces student achievement (Hilliard III, 2000). For accountability systems to achieve their intended purpose of school reform, outcome scores must be used to identify students and schools who need more resources to meet state standards. Thurlow and Johnson (2000) have noted that high-stakes testing for students with disabilities could have the potential of increasing expectations or the disadvantage of increasing retention in grade and drop out rates. For students with severe disabilities, performance on alternate assessment could also have the potential of increasing expectations or the disadvantage of competing with instructional time and producing meaningless results. Kentucky was the first state to include all students in a statewide accountability system including the use of an alternate assessment portfolio for students who could not participate in large-scale testing (Kleinert, Kearns, & Influences on Student Outcomes / 255 Kennedy, 1997). A statewide survey revealed that teachers reported gains in student learning (e.g., being able to follow a schedule) and other positive outcomes (e.g., increased percentage of student augmentative communication systems; Kleinert, Kennedy, & Kearns, 1999). Teachers in this statewide survey also reported that alternate assessment was a timeintensive process (Kleinert et al., 1999). Although outcome data are still emerging from the initial implementation of alternate assessment, it is conceivable that many teachers will have one or more students who did not achieve state expectations for performance. For example, pilot data in North Carolina, a state with some of the highest expectations for student performance on the alternate assessment, show that, while most students made progress on their IEP objectives, fewer than half of the students achieved mastery of their IEP objectives that were included in the alternate assessment (North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, 2001). Similarly, in Kentucky in the first year of alternate assessment implementation, only a small number of students met expectations for proficient performance in the first year of implementation. By the third year, fewer than 50% of those who participated in the alternate assessment scored proficient or distinguished (Kleinert et al., 1997). When outcomes are disappointing, there is the temptation to lower expectations. States facing large numbers of students scoring poorly on an alternate assessment might lower the outcomes expected for this population. Or, states may decrease the impact of these scores in school accountability equations. Some states may lower expectations for students with severe disabilities before the scores are even obtained. This occurs if states assume all students in the alternate assessment should be assigned to the lowest rank score because they did not take the large-scale assessment. Such rank assignment provides a disincentive to encourage achievement for students with severe disabilities (Bechard, 2001). Schools or teachers may also lower expectations. This may occur by: (a) expecting lower outcomes from the onset of the school year (e.g., that a specific student will not make progress on the standards); (b) measuring small, trivial goals that do not relate to quality 256 / of life (e.g., put a peg in a pegboard); (c) shifting the focus to teacher performance (e.g., will participate with “physical guidance”); or (d) measuring program variables (e.g., the student has a schedule). When an alternate assessment is linked to the student’s own IEP, all students are capable of mastering expectations set for their educational program. The alternative to lowering expectations is to hold firmly to high expectations and identify ways to help more students achieve these standards. The purpose of this article is twofold. First, we provide a theoretical framework for the variables that may influence alternate assessment outcome scores. Second, we consider the subset of these variables that relate directly to student learning and discuss ways school teams my influence these variables. Variables that May Influence Alternate Assessment Outcome Scores There are six variables that can influence outcome scores as shown in Figure 1. The first three variables go beyond the classroom level. These include the technical quality of the alternate assessment format, resources, and student risk factors such as absence, illness, multiple foster placements, and behavioral crises. The last three variables are ones that the teaching team can influence directly including curriculum access, data collection, and instructional effectiveness. Each of these will now be discussed briefly. Technical Quality of the Alternate Assessment Format Developing guidelines for the participation of students in alternate assessments was a new and difficult challenge that most states addressed between 1998 and 2000. Several experts offered recommendations for development of these procedures soon after passage of the 1997 Amendments of IDEA (Elliott, Ysseldyke, Thurlow, & Erickson, 1998; Kleinert et al., 1997; Ysseldyke & Olsen, 1999). By the 2001 report of the National Center on Education Outcomes (NCEO), nearly all states were working on some aspect of alternate assessment. The NCEO report (Thompson & Thurlow, 2001) found that most states Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities-September 2003 Figure 1. Variables that influence alternate assessment outcome scores. had developed the format for these assessments with a variety of stakeholders including special education personnel, parents, state assessment personnel, and advocates. Nearly half of the states (48%) chose to use portfolio assessment. Others chose to use a checklist, an IEP analysis or some other format. Research in general education in the use of performance-based indicators like portfolios has revealed poor reliability due to lack of agreement among tasks, raters and other sources of measurement error (Koretz, Stecher, Klein, & McCaffrey, 1994; Shavelson, Baxter, & Gao, 1993). While research is still emerging on the technical quality of alternate assessments, it is conceivable that they will also reflect issues of measurement error. Given the possibility of measurement error, school teams need to be informed consumers about administration of their state or district’s alternate assessment format. The team may especially want to understand the specific guidelines used for scoring to identify criteria used to assign outcome scores. For example, in North Carolina, where the alternate assessment has a strong focus on mastering IEP goals, portfolio scorers look for evidence of mastery, initiation, and generalization of each objective. It also is important that administrators and parents understand exactly what criteria are used in assigning the alternate assessment scores and who makes these decisions. Besides understanding criteria used for scoring the alternate assessment, school teams and teachers also need to request information on technical quality of the alternate assessment that the state has collected. For example, Delaware has published descriptive statistics about reliability of its alternate assessment portfolio (Burdette, 2001). Tindal et al. Influences on Student Outcomes / 257 (2002) have evaluated reliability and construct validity for Oregon’s alternate assessment and found a relationship between scores and the student’s disability. Some states (e.g., North Carolina) use trained scoring panels and require that scorers demonstrate reliability prior to evaluating assessment materials. In this early stage of implementation of alternate assessment, it may be difficult to know what expectations to have for technical quality. In Kentucky, where alternate assessment began in the early 1990s, scoring reliability continued to be close to 50% in the third year of scoring (e.g., 51.9% for portfolios scored the same for accountability purposes each year). This level of reliability did not change despite initiation of a new set of scoring rules in 1994 –1995 (Kleinert et al., 1997). On a survey conducted with teachers between 1995 and 1997 in Kentucky, several teachers also wrote comments that the scoring was too subjective (Kleinert et al., 1999). After new scoring procedures were instituted in Kentucky in the spring of 2001, interrater agreement was 73% (personal correspondence with Mike Burdge). The lesson to be learned for all states from the Kentucky experience is that ongoing work is needed to improve reliability of scoring for alternate assessments. This is especially crucial if these scores will be used to meet the requirements of NCLB for outcome scores in language arts, math, and science for students with significant cognitive disabilities. Resources Another variable that can influence outcome scores on the alternate assessment is allocation of resources to teach students skills related to state standards and to complete the alternate assessment process. Alternate assessment as mandated by the 1997 Amendments of IDEA is one of the largest changes required in special education services since the advent of the Individualized Education Plan in 1975. In many states a portfolio is used that requires substantial assessment, planning, and paperwork documentation. For example, in the Kentucky survey, teachers expressed frustration with the amount of time needed to complete assessment portfolios (Kleinert et al., 1999). The question that arises is how time will be reallocated for this new requirement. 258 / Do teachers sacrifice personal time? Do schools reallocate or increase resources to give teachers release time to work on the portfolios? For example, one school system in North Carolina has hired substitutes to release teachers doing portfolios four days per year to meet this time consuming requirement. Or, do students lose instruction while teachers summarize assessment protocols during the school day? Besides time, other resources may be needed to help students meet increased expectations. Students may need assistive technology, new instructional materials, community-based opportunities for job training, and access to general education classes to meet state standards. A second type of resource that may influence outcome scores is staff training. In its analysis of the impact of the new IDEA requirements, Congress noted the substantial professional development needs that would occur with the inclusion of all students with disabilities in large-scale assessments (Notice of Proposed Rule Making, 1997). In their study on variables that influenced alternate assessment outcome scores, Kampfer, Horvath, Kleinert, and Kearns (2001) found that the use of “best practices,” more than the amount of time spent preparing a portfolio, influenced outcome scores. Given that a certain amount of increased teacher planning time is needed to do the portfolios, this time may be more fruitful if teachers have been trained in the quality indicators reflected in the alternate assessment process. For example, several states require documenting performance of the skill across environments. Teachers may need training in how to teach and assess generalization using strategies like those of Horner, Sprague, and Wilcox (1982). Or, performance of state standards may require using new forms of assistive technology or expanding students’ vocabularies in their current system. If the portfolio is to include student self-evaluation of performance, teachers may need training in self-determination (Kleinert et al., 2001). Risk Factors A third variable that may influence student outcomes is the risk factors that create student instability in daily performance. Students Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities-September 2003 whose instability is due to behavioral crises may need comprehensive behavioral support (Horner, Albin, Sprague, & Todd, 2000). Students may need functional assessment of behavior, environmental supports like predictable routines, and training in using communicative alternatives to problem behavior. In their resource on positive behavioral support, Bambara and Knoster (1998) also describe several lifestyle interventions that may be needed for students to overcome challenging behaviors. These include addressing lifestyle issues like limited opportunities for choice and control, loneliness, and exclusion. Positive behavior support, combined with strategies to improve curriculum and instruction, may be essential in meeting state expectations. While some of this support may be instructional (e.g., conducting functional assessment and teaching communicative alternatives), it may also require going beyond the instructional context (e.g., creation of new opportunities, procurement of wraparound services, medical referral). Students with severe disabilities may also have unstable performance due to illness or conditions that cause progressive neurological impairment. For such students, special health care procedures become part of the equation in considering how to optimize learning outcomes. For example, staff may need to monitor seizures closely to help families communicate with medical professionals in planning medication changes or other treatments. For students who are medically fragile and have 24 hour nursing care, planning with nursing staff to identify optimal learning times may be crucial. Access to the General Curriculum Students with severe cognitive disabilities have often been taught a separate, functional curriculum. If students have little to no exposure to the general curriculum, it is unlikely that they will show progress on state standards. Two major influences have occurred in planning curriculum for students with severe disabilities in the last three decades. The first has been to identify curriculum that relates to real life or what Brown, Nietupski, and HamreNietupski (1976) called using the “criterion of ultimate functioning” in daily life to select teaching goals. Many call this a functional or life skills curriculum approach. The second influence has been the increased inclusion of students with severe disabilities in general education settings. This inclusion has led to what some call the development of parallel curriculum and curriculum overlapping (Giangreco, Cloninger, & Iverson, 1998), in which students learn either adaptations of the general curriculum or ways to participate in class activities using their life skills. Current school reform efforts include states and districts setting standards for student performance. Thompson, Quenemoen, Thurlow, and Ysseldyke (2001) have described both the legal precedence and practical reasons for not having separate standards for students with disabilities. Increasingly, states are seeing the extension of state standards to all students with disabilities and the development of alternate assessments as interrelated activities. While in 1999, 32% of states were using only functional skills for their alternate assessments with no link to state standards, by 2001 only 8% were doing so. Nearly all states were finding some way to extend state standards to all students. Because of the complexity of extending standards for students with severe disabilities, many states have developed guidelines for teachers to follow. These may be called “extended standards,” “real life indicators,” or other terms. These guidelines are creating a bridge between functional, life skills curricula and traditional general education curricular topics like reading, math, science, and social studies (Browder et al., 2002). For example, in the Kansas Extended Curricular Standards-Mathematics (Kansas State Department of Education, 2000), the benchmark for Extended Standard 3-Geometry is “The learner demonstrates an understanding of spatial properties and relationships in a variety of situations.” Examples are provided across school, vocational/career, community, recreation and leisure, and home environments. One of the community examples is “Walks ‘between’ the lines to cross a downtown street.” One for recreation and leisure is, “Knows that the rules require a player to hit a volleyball/badminton ‘over’ the net.” If planning teams are only given the state standard or benchmark (e.g., “understanding of spatial properties”) without examples of real life indicators, they may Influences on Student Outcomes / 259 struggle with the creative brainstorming needed to find these links. Data Collection Once decisions have been made about addressing state standards and gaining access to the general curriculum as they relate to alternate assessment and the IEP, decisions must be made about whether students are making progress towards these criteria. Substantial research now exists on how to monitor and evaluate progress for students with moderate and severe disabilities using direct, ongoing data collection (Browder, Demchak, Heller, & King, 1991; Farlow & Snell, 1994; Grigg, Snell, & Lloyd, 1989; Liberty, Haring, White, & Billingsley, 1988). This research also provides guidelines for linking instructional strategies to data patterns (e.g., Browder, 1993; Farlow & Snell, 1994). The challenge is to figure out how longstanding methods of data collection relate to the state’s alternate assessment process. While some states link the alternate assessment to the IEP, others use checklists or portfolios (Thompson & Thurlow, 2001). It may be difficult to find a link between the alternate assessment and the record of progress teachers have obtained while tracking IEP objectives. If the alternate assessment does not have a clear link to the IEP, teachers may need guidelines on how to track progress for this new requirement. Early research on task analytic assessment suggested that students with severe disabilities might perform better when the steps used to track progress are more specific (Crist, Walls, & Haught, 1984) and nonessential steps are omitted (Williams & Cuvo, 1986). Also, instructional progress for students with severe disabilities is usually tracked across time versus in a one-time assessment. One of the early criticisms of using standardized assessments for this population is that they often yielded information of little educational relevance (Sigafoos, Cole, & McQuarter, 1987). Alternate assessments developed to be a one-point-in-time measure may fail to capture student’s ability to perform skills related to state standards. In contrast, although ongoing data collection is more likely to capture student progress, it too has disadvantages such as the risk of observer (i.e., 260 / teacher) bias or inconsistency and the time required to collect and summarize the data. Thus, it becomes essential in interpreting alternate assessment outcomes to ask, “How representative of the students’ performance was the data collection?” Instructional Effectiveness As mentioned at the beginning of this paper, it is teaching, not testing that promotes student learning (Hilliard, 2000). Numerous resources now exist that outline methods of instruction for students with severe disabilities (e.g., Cipani & Spooner, 1994; Snell & Brown, 2000; Westling & Fox, 2000). Students may not receive the benefit of these instructional strategies because of teacher shortages that lead to hiring teachers out of field or through emergency certificates. Teachers also may not implement effective practices even when trained to do so. Even teachers committed to best practice procedures may be confused about the link between instruction and alternate assessment outcomes especially when there is no defined relationship to the IEP in their states’ process. Need for Research on Outcomes Recent legislation such as No Child Left Behind (2002) suggests that the era of accountability will not only continue, but become more pronounced in years to come. If students with severe cognitive disabilities are not to be “left behind,” research is needed on variables that influence alternate assessment outcome scores. Six sets of variables described here provide a starting point for this research. For example, data could be collected on interrater reliability for the alternate assessment score, student absences, amount of teacher training, time in general education classrooms, number of IEP goals related to state standards, frequency of data collection, and instructional quality to explore correlation with outcome scores. Promoting Student Learning in the Era of Accountability In an era of accountability, it is important not to lose sight of students making meaningful Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities-September 2003 progress on an IEP that reflects the students’ priorities as well as alternate assessment outcome scores. “Teaching to the test” means only providing instruction on material that will be scored and publicly reported versus responding to students broader curricular needs. Students with severe disabilities do need direct instruction on performance indicators used for state standards addressed in alternate assessment. “Teaching to the test” by addressing state standards in ongoing instruction can be a positive step to accessing the general curriculum. In contrast, only doing those activities that promote alternate assessment outcome scores may bypass meaningful student learning. The following are guidelines to keep the focus on meaningful student learning while also being responsive to realities of state and national accountability requirements. Guideline 1: Consider both individual student needs and state standards in developing the IEP Updating students’ curricula to reflect the new priorities established by the state standards used for alternate assessments is complicated by the fact that curriculum for students with moderate and severe disabilities must also be personalized (Knowlton, 1998). Nearly all guidelines for developing curriculum for students with severe disabilities recommend a personalization process through considering student preferences, parental priorities, and environmental assessments (Browder, 1993; Giangreco, Cloninger, & Iverson, 1998). This personalization often involves team planning (Campbell, Campbell, & Brady, 1998; Falvey, Forest, Pearpoint, & Rosenberg, 1994). The team typically will use person-centered planning (Mount & Zwernik, 1988), which recent research indicates encourages student and parental input (Hagner, Helms, & Butterworth, 1996; Miner & Bates, 1997). Thus in responding to alternate assessments, teachers will need to work not only from a school system’s or state’s curriculum, but also from the student’s personalized curricular priorities. While it may seem paradoxical to try to focus on students’ personalized priorities and statedetermined outcome criteria, this balance may be achieved by expanding the team curriculum planning process to determine how these priorities can be reconciled. To meet the dual priorities of addressing state standards and individual needs, consideration needs to be given to both during the IEP process. Thompson et al. (2001) describe how state standards were considered in planning for a student named Lara. One of her individual needs for education was the expansion of her use of augmentative communication systems. This need could be addressed concurrently with several state standards. For example, considering the reading standard “Students read a variety of materials, applying strategies appropriate to various situations” and additional standards in listening and technology, the IEP team developed this goal as a link to the state standards: “Lara will look at and listen to a story that is being read to her and touch a switch to ‘read’ a word from an icon when she sees and hears it in the text.” Table 1 provides additional examples of how state standards can be expanded to address individual student priorities based on some of North Carolina’s standards. Guideline 2: Set high expectations for active student learning One of the challenges teachers face in extending state or local standards is defining specific, observable and measurable skills to target for student mastery, especially for students who require extensive support in daily living. Ford, Davern, and Schnorr (2001) warn that in the rush to address state standards, teams may select trivial skills that do not create meaningful learning experiences. In contrast, some teams may have trouble identifying any skills that really are reading and math or related to other state standards. The student may be medically fragile, use a feeding tube, need nursing care, or have only small range of motion in one or two body parts. Or, the student may be deaf/blind or have no symbolic communication. Creating access to the general curriculum to address state standards can, at first, seem “unrealistic.” The minimum that is needed to write IEP objectives is one observable, measurable voluntary response. If one response is identified, it can be shaped to be a choice response to help the student make choices in all life areas. For example, if the student can look up voluntarily, or move a hand slightly, or make a noise, the teacher can train this to be a signal to say “yes.” IEP objectives then may include skills like moving the hand to indicate readiness for Influences on Student Outcomes / 261 TABLE 1 Examples of State Standards Extended for Access to General Curriculum North Carolina Standard Course of Study Example of Individualized Goal that Links to Standard Grade 2 Info. Skills/Comp. Goal 15 The learner will communicate reading, listening, and viewing experiences Grade 2 Info. Skills/Comp. Goal 1 The learner will explore sources and formats for reading, listening, and viewing purposes Grade 2 Mathematics Comp. Goal 2 The learner will recognize, understand, and use basic geometric properties, and standard units of metric and customary measurement Grade 3 Mathematics Comp. Goal 2 The learner will recognize, understand, and use basic geometric properties, and standard units of metric and customary measurement Kindergarten Mathematics Comp. Goal 3 The learner will model simple patterns and sorting activities Use eye blink to communicate preference between two familiar books. Comprehend “big idea” of story through recognition of sight words. Identify and use dollars or coins to make purchases. Select correct measuring cup with aid of picture recipe. Return leisure items or school supplies to storage bins by shape or symbol on bin. Note: The authors express their gratitude to Susan Griffin who helped create these examples. tube feeding, or looking up to indicate a desire to go inside/outside, or vocalizing to indicate the need for a break from a work session, can be expanded to address language arts activities like participation in the telling of a story. For some students this voluntary response may be as subtle as a change in respiration or a small shift of the head. For example, in developing IEP goals for a student with spastic quadriplegia who was legally blind, Browder and Martin (1986) identified clucking the tongue and a small movement of one hand as voluntary, observable responses. His teacher, Doris Martin, taught this student to use this tongue cluck to make choices and to use the small movement in one hand to operate switches. These two responses opened the door to more curricular options. Because it is often impossible to determine the comprehension level of students with complex physical disabilities, it is crucial not to underestimate academic potential. If the subtle responses are only used for choices, the student may not learn to use the response to demonstrate understanding of more complex concepts. In addition to choice, subtle responses may be used to teach giving answers, such as blinking to indicate agreement with the answer to a math problem or reading 262 / comprehension question, or using number sequences. For example, a Charlotte teacher who conducted alternate assessment for students with significant disabilities decided to try to increase expectations for her students. In the past, she had often given students choices, but noted that they did not necessarily have to comprehend the question to make a choice response (e.g., they might randomly hit a switch). She began to ask students factual recall questions about their daily experiences and stories she read. One of the first successes occurred when a student who had no symbolic communication beyond hitting a switch to make choices mastered an IEP objective to answer questions about her daily routine by choosing between two Big Mac switches (e.g., “Who brought you to school today- Mom or Aunt Sarah?”). The next step was to apply this to story comprehension (e.g., “Who found the kitten- Ted or Mary?”) A pitfall to avoid is defining objectives that are passive; that is, objectives that define what the teacher will do versus a voluntary student response. For example, “sitting while a story is read” (for a student who cannot move anyway), “tolerating touch,” and “experiencing new job activities” do not require the student to make a response, but instead require the Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities-September 2003 TABLE 2 Examples of Passive Objectives Converted into Active Ones Passive Objectives Active Objectives 1. Given hand over hand and full assistance, Billy will count out 1–5 objects. (Problem: Billy has quadriplegia and will never be able to move and count objects alone. This objective keeps him passive and does not help determine whether he is recognizing the concept of number.) 1. Billy will push a universally mounted Big Mac button to say “stop” immediately after a peer or teacher counts out the target number of objects (e.g., 3) in a set for 1–5 objects. (Improvement: Through active participation in this objective, Billy’s teacher can determine whether he has recognized the concept of number.) 2. After Sherrie’s arms are placed in midline, she will use a two-s witch communication board to answer 4/5 questions about her daily routine. (Improvement: Sherrie still is working at midline but now she has a purpose and active response to make. Sherrie is also now using assistive technology and working on symbols via switch use-a link to the general curriculum.) 3. Jose will turn his head to indicate which of two types of cloth he wants his caregiver to use in wiping his face or will nod to indicate “both” for 4/5 times across the day. (Improvement: Now Jose lets the caregiver know what he wants. By including the option of choosing “both”, the teacher incorporates numeracy, a link to a math standard.) 4. Kenu will participate in music, dancing or group games by visually locating and tracking the person who is taking the lead for 4/5 trials. (Improvement: Kenu now is gaining a way to join in the fun of age appropriate early teen activities. He still will be learning to sharpen his visual and auditory tracking skills. By answering questions like “Who’s singing?” or “Who’s turn is it?” Kenu is building listening comprehension as well as literacy skills. As Kenu’s comprehension builds, this response can also become a choice. “Who would you like to hear sing next?”) 2. Sherrie will bring her arms to midline to participate in reading lessons given physical assistance and verbal prompts for 4/5 trials. (Problem: While Sherrie needs exercises to increase her range of motion, she does not have the physical ability to bring her own arms to midline. This objective is about what the professionals are doing-moving her arms. The objective also has no real focus on the lesson’s content.) 3. Jose will tolerate having his face washed on 4/5 trials. (Problem: Jose is being trained to be passive; to “tolerate” caregiving whether or not it respects his preferences. The goal also misses the opportunity for an academic link.) 4. Kenu will track a visual or auditory stimulus from midline to lateral and back across midline on 4/5 trials. (Problem: This objective comes from an infant stimulation curriculum. The teacher typically uses infant toys in teaching it. What is its purpose for Kenu who is now 13? The challenge is that due to Kenu’s physical disability, his only voluntary movement is his ability to move his eyes.) teacher to make one. To be educational, IEP objectives must be focused on responses the student can make voluntarily. Even if responses are not purposeful at the onset, the purpose of instruction may be to shape them as purposeful (e.g., communicative) responses. Table 2 provides examples of passive objectives converted into active ones. Guideline 3: Summarize data collected across time to capture student performance To best capture student progress, teachers need to collect data across time on skills that are linked to state standards. Browder (2001) has described several methods of data collec- tion such as task analysis, repeated trial assessment, repeated opportunity assessment, and duration. The Charlotte Alternate Assessment Model Project (U S Department of Education, OSERS Grant # H324M00032) also has developed numerous examples for each of these methods of data collection, based on fictitious students, real students, and adaptations of research, which are available on line at www. uncc.edu/aap. An example from this web site is provided in Figure 2. Two recent books on alternate assessment by Kleinert and Kearns (2001) and Thompson et al., (2001) offer other models for collecting information on Influences on Student Outcomes / 263 Figure 2. Example data collection for repeated opportunity. student progress. Given the variation in how states conduct alternate assessment, teachers may want to compare multiple resources to determine which data collections methods best address their state’s requirements. 264 / Besides quantitative data collection methods, many states’ alternate assessment procedures require qualitative assessment. Several strategies exist for the completion of portfolios that use these qualitative methods (Swice- Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities-September 2003 Figure 3. Sierra’s line of progress toward goal. good, 1994; Salend, 1998; Thompson et al., 2001). Some materials may showcase the student’s best work. Technology may be beneficial for collecting material to showcase including scanning student-produced work, entering sound and video clips of student performance, or using digital pictures of the student performing the skill across settings. Selected copies of notes from home may illustrate student progress or generalization. Portfolios may also be reflective by including teacher anecdotal notes or student self-evaluation. Student self-evaluation may be “lowtech” like completing a sample statement (e.g., “I am proud of . . . ”), stamping (e.g., “My best work” on top of teacher’s data sheet), or using a graph (e.g., rings on a dowel to show number completed). Or, student selfevaluation may be “high-tech.” For example, Denham and Lahm (2001) describe the use of custom overlays for IntelliKeys that students can use to self-evaluate with responses like “Yes I did.” Or, “will do better at.” A cumulative portfolio contains items collected for an extended period of time. For example, student work samples may be used to show progress over time using a distinctive mark as a signature or pictures of the wide range of settings where the student has completed job tryouts. Guideline 4: Integrate state standards and alternate assessment expectations in daily instruction Few students will be able to meet state standards unless the standards are taught as part of daily instructional procedures. Clayton, Burdge, and Kleinert (2001) describe six steps to embed alternate assessment into daily instruction from day one. These include: (a) identifying the primary settings and classes in which the student’s objectives will be covered, (b) developing data collection sheets, (c) designing instructional strategies for each objective, (d) adapting materials, (e) embedding data and instructional strategies into the daily classroom routine, (f) monitoring and revising the program as necessary, and (g) organizing the ongoing data. Linking the alternate assessment to the IEP makes it possible to consider both concurrently through the ongoing instruction and data collection that have been longstanding practices for students with severe disabilities. Thus, throughout the school year, the teacher is providing direct instruction on the skills to be included in the alternate assessment and organizing data to document progress not only for the IEP, but also for the portfolio or other alternate assessment process. To be sure students will meet expected out- Influences on Student Outcomes / 265 Figure 4. Example of qualitative summary for the alternate assessment portfolio. comes, some type of “pacing guide” is needed. One alternative is to use a line of progress as shown in Figure 3. The teacher draws a line from the student’s starting point (baseline) to the level of progress expected for the review period (e.g., first quarter). By reviewing ongoing data, the teacher can determine whether the student is keeping pace with expectations and make adjustments in instruction as 266 / needed. For example in Figure 3, Sierra’s IEP ends on March 15 and the criteria for mastery is 100%, so an aimstar is placed at 100%. A line of progress was then drawn from the current data point to this “aim.” As each session’s data are interpreted, it becomes clear whether or not the data are above or below this line of progress. In the example for Sierra’s prices in Figure 3, the target is for Sierra to master Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities-September 2003 TABLE 3 Planning when Generalization or Initiation Has Not Occurred Problem (Check which applies) 1. Student has made no progress on this skill. 2. Training in a variety of settings or with a variety of people has not occurred. Potential Solution Examples of Application Continue to teach skill in a variety of contexts while giving consideration to ways to simplify the required response (e.g., use of assistive technology). Determine challenges to training for generalization and plan for changes to incorporate this variety. Use dollar matching card for making a p urchase versus counting dollars. Use a picture card to assist in placing an order. 3. Data/notes/other information on generalization and initiation have not been taken or are unreliable. 4. Student performs skill in target setting, but not in other contexts. Plan for staff training or time management needed to get this information. 5. Student does not have to initiate skill because others do it for him/her. Develop a plan to encourage all team members to wait for/praise initiation. Provide direct training in variety of contexts. Use common materials or other cues to help student generalize. reading the prices by session 36. She had 100% correct well before this aim, in fact by session 18. She mastered reading the prices more quickly than expected and read them consistently by the end of the IEP year. The teacher will also document how Sierra used these prices across a variety of contexts (generalization) and initiated reading prices through anecdotal notes or other assessments. Another alternative to determine if progress is adequate is to use a phase mean every two weeks. For example, if the student begins with zero correct and the goal is 20 correct, in 10 reviews (20 weeks), the student will need to master at least one new response each review. Unlike Sierra’s example, student progress may not keep pace with expectations. In these instances, teachers need a method to decide how to change instruction to make it more effective. Browder (2001) has described instructional guidelines that include looking at Has only worked on signature in classroom. Create opport unities to use in library, music, and gym by having students sign up for activities & materials. Teach student to prompt feedback from parents and other teache rs by using a “Have you seen me read today?” form. Student uses picture cards to make requests only at snack with teacher. Introduce other requests (pictures) just after snack by asking, “What do you want to do next?” Make duplicate set of cards for use at home. Make picture reminder for all staff to wait for student to check own schedule. After 3 m inutes, use nonspecific cue, “I wonder what’s next.” patterns of inadequate or no progress, adequate progress, and regression, and considering the types of instructional changes needed for each. For example, when progress has occurred, but at too slow a pace, methods of fading teacher assistance (prompting) may be beneficial. When qualitative assessments are used, teachers also need strategies for evaluating the qualitative data against the criteria used for the alternate assessment. An example of this is shown in Figure 4. In North Carolina, three important criteria used in assigning an alternate assessment outcome score are mastery, generalization, and initiation of the skill. Using a quarterly progress report, the teacher writes examples of the student’s performance related to each of these criteria. If a qualitative summary reveals problems in student progress, it may be useful to have a planning sheet to guide the decision-making. Table 3 Influences on Student Outcomes / 267 provides an example of a guide for making decisions about how to improve a student’s generalization and initiation of skills. Summary The purpose of standards-based reform is that all students achieve expected state and local standards. While large-scale testing is often used to assess achievement of these standards, most students with severe disabilities participate in alternate assessments. These alternate assessments provide a format for students to demonstrate achievement of state standards that have been extended to accommodate the unique educational needs of this population. Alternate assessments provide an important opportunity to increase expectations for students with severe disabilities. Because of their link to state academic standards, they provide an incentive for increasing access to the general curriculum. In reviewing states’ alternate assessments, Browder et al. (2002) found that most states focus on mastery or progress as the alternate assessment outcome score. Focusing on student achievement also sets the expectation that all students can learn. Because these increasing expectations are new, initial outcomes may be disappointing. This article has proposed a conceptual framework to guide understanding of influences on alternate assessment scores and recommendations for keeping the focus on high expectations for student learning in an era of accountability. References Bambara, L. M., & Knoster, T. (1998). Designing positive behavior support plans. Innovations, 13, 25–30. Bechard, S. (2001). Models for reporting the results of alternate assessments within state accountability systems: NCEO synthesis report 39. Retrieved March 14, 2002 from http://www.education.umn.edu/ NCEO/OnlinePubs/Synthesis39.html. Browder, D. (1993). Assessment of individuals with severe disabilities. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes. Browder, D. M. (2001). Curriculum and assessment for students with moderate and severe disabilities. New York: Guilford. Browder, D., Ahlgrim-Dezell, L., Flowers, C., Karvonen, M., Spooner, F., & Algozzine, R. (2002, April). How states define alternate assessment for students with disabilities. Paper presented at the An- 268 / nual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans. Browder, D., Demchak, M. A., Heller, M., & King, D. (1991). An in vivo evaluation of data-based rules to guide instructional decisions. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 14, 234 – 240. Browder, D. M., & Martin, D. K. (1986). A new curriculum for Tommy. Teaching Exceptional Children, 18(4), 261–265. Brown, L., Nietupski, J., & Hamre-Nietupski, S. (1976). Criterion of ultimate functioning. In M. A. Thomas (Ed.), Hey, don’t forget about me! (pp. 2–15). Reston, VA: Council for Exceptional Children. Burdette, P. (2001). Alternate assessment: Early highlights and pitfalls of reporting. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 26, 61– 66. Campbell, P. C., Campbell, C. R., & Brady, M. P. (1998). Team environmental assessment mapping system: A method for selecting curriculum goals for students with disabilities. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 33, 264 –272. Cipani, E., & Spooner, F. (1994). Curricular and instructional approaches for persons with severe disabilities. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Clayon, J., Burdge, M., & Kleinert, H. L. (2001). Systematically teaching the components of selfdetermination. In H. L. Kleinert, & J. F. Kearns (Eds.), Alternate assessment: measuring outcomes and supports for students with disabilities (pp. 93–134). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes. Crist, K., Walls, R. T., & Haught, P. (1984). Degrees of specificity in task analysis. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 89, 67–74. Denham, A., & Lahm, E. A. (2001). Using technology to construct alternate portfolios of students with moderate and severe disabilities. Teaching Exceptional Children, 33(5), 10 –17. Elliott, J., Ysseldyke, J., Thurlow, M., & Erickson, E. (1998). What about assessment and accountability. Teaching Exceptional Children, 31(1), 20 –27. Falvey, M., Forest, M., Pearpoint, J., & Rosenberg, R. (1994). Building connections. In J. Thousand, R. Villa, & E. Nevin (Eds.), Creativity and collaborative learning: A practical guide to empowering students and teachers (pp. 347–368). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes. Farlow, L. J., & Snell, M. E. (1994). Making the most of student performance data. Innovations, 3. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation. Ford, A., Davern, L., & Schnorr, R. (2001). Learners with significant disabilities: Curricular relevance in an era of standards-based reform. Remedial and Special Education, 22, 214 –222. Giangreco, M. F., Cloninger, C. J., & Iverson, V. S. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities-September 2003 (1998). Choosing options and accommodations for children (2nd Ed., pp. 29 –95). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes. Grigg, N. C., Snell, M. E., & Loyd, B. H. (1989). Visual analysis of student evaluation data: A qualitative analysis of teacher decision-making. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 14, 13–22. Hagner, D., Helm, D. T., & Butterworth, J. (1996). “This is your meeting”: A qualitative study of person-centered planning. Mental Retardation, 34, 159 –171. Hilliard, A. G., III (2000). Excellence in education versus high-stakes standardized testing. Journal of Teacher Education, 51, 293–304. Horner, R. H., Albin, R. W., Sprague, J. R., & Todd, A. W. (2000). Positive behavior support. In M. E. Snell & F. Brown (Eds.), Instruction of students with severe disabilities (5th ed., pp. 207–290). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Horner, R. H., Sprague, J. R., & Wilcox, B. (1982). Constructing general case programs for community activities. In B. Wilcox & G. T. Bellamy (Eds.), Design of high school programs for severely handicapped students (pp. 61–98). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes. Kampfer, S. H., Horvath, L. S., Kleinert, H. L., & Kearns, J. F. (2001). Teachers’ perception of one state’s alternate assessment: Implications for practice and preparation. Exceptional Children, 67, 361–373. Kansas State Department of Education. (2000). Kansas extended curricular standards for mathematics. Topeka, KS: Author. Kleinert, H. L., Denham, A., Groneck, V. B., Clayton, J., Burdge, M., Kearns, J. F., et al. (2001). Systematically teaching the components of selfdetermination. In H. L. Kleinert & J. F. Kearns (Eds.), Alternate assessment: Measuring outcomes and supports for students with disabilities (pp. 93–134). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes. Kleinert, H. L., & Kearns, J. F. (1999). A validation study of the performance indicators and learner outcomes of Kentucky’s alternate assessment for students with significant disabilities. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 24, 100 –110. Kleinert, H. L., & Kearns, J. F. (2001). Alternate assessment: Measuring outcomes and supports for students with disabilities. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes. Kleinert, H. L., Kearns, J. F., & Kennedy, S. (1997). Accountability for all students: Kentucky’s alternate portfolio system for students with moderate and severe cognitive disabilities. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 22, 88 – 101. Kleinert, H. L., Kennedy, S., & Kearns, J. F. (1999). The impact of alternate assessments: A statewide teacher survey. Journal of Special Education, 33, 93–102. Knowlton, E. (1998). Considerations in the design of personalized curricular supports for students with developmental disabilities. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 33, 95–107. Koretz, D., Stecher, B., Klein, S., & McCaffrey, D. (1994). The Vermont portfolio assessment program: Findings and implications. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 13, 5–16. Liberty, K. A., Haring, N. G., White, O. R., & Billingsley, F. (1988). A technology for the future: Decision rules for generalization. Education and Training in Mental Retardation, 23, 315–326. Miner, C. A., & Bates, P. E. (1997). The effect of person centered planning activities on the IEP/ transition process. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 32, 105–112. Mount, B., & Zwernik, K. (1988). It’s never too early, it’s never too late: A booklet about personal-futures planning for persons with developmental disabilities, their families, and friends, case managers, service providers, and advocates. St. Paul, MN: Metropolitan Council. No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, Pub. L. No. 107–110, 115 Stat.1425 (2002). North Carolina Department of Public Instruction. (2001). Report of student performance: North Carolina alternate assessment portfolio pilot program, 1999 –2000. Raleigh, NC: Author. Notice of Proposed Rule Making, Assistance to States for the Education of Children with Disabilities, Preschool Grants for Children with Disabilities, and Early Intervention Program for Infants and Toddlers with Disabilities, U S Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitation Services, 62 Fed. Reg. 55026 (Oct. 22, 1997). Salend, S. J. (1998). Using portfolios to assess student performance. Teaching Exceptional Children, 31(2), 36 – 43. Shavelson, R. J., Baxter, G. P., & Gao, X. (1993). Sampling variability of performance assessments. Report on the status of generalizability performance: Generalizability and transfer of performance assessments. Los Angeles, CA: National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED359229) Sigafoos, J., Cole, D. A., & McQuarter, R. (1987). Current practices in the assessment of students with severe handicaps. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 12, 264 –273. Snell, M. E., & Brown, F. (2000). Instruction of students with severe disabilities. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Influences on Student Outcomes / 269 Swicegood, P. (1994). Portfolio-based assessment practices. Intervention in School and Clinic, 30(1), 6 –15. Tindal, G., Almond, P., McDonald, M., Crawford, L., Tedesco, M., Glasgow, A., et al. (2002). Alternate assessments in reading and math: Development and validation for students with significant disabilities. Manuscript submitted for publication. Thompson, S. J., Quenemoen, R. F., Thurlow, M. L., & Ysseldyke, J. E. (2001). Alternate assessments for students with severe disabilities. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. Thompson, S., & Thurlow, M. L. (2001). 2001 state special education outcomes: A report on state activities at the beginning of a new decade. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Retrieved September 5, 2001, from http://education.umn.edu/NCEO/ OnlinePubs/onlinedefault.html 270 / Thurlow, M. L., & Johnson, D. R. (2000). Highstakes testing of students with disabilities. Journal of Teacher Education, 51, 305–14. Westling, D. L., & Fox, L. (2000). Teaching students with severe disabilities (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill. Williams, G. E., & Cuvo, A. J. (1986). Training apartment upkeep skills to rehabilitation clients: A comparison of task analytic strategies. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 19, 39 –51. Ysseldyke, J., & Olsen, K. (1999). Putting alternate assessment into practice: What to measure and possible sources of data. Exceptional Children, 65, 175–185. Received: 4 September 2002 Initial Acceptance: 3 October 2002 Final Acceptance: 10 December 2002 Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities-September 2003