Institutional Strategies for Postsecondary Student Success

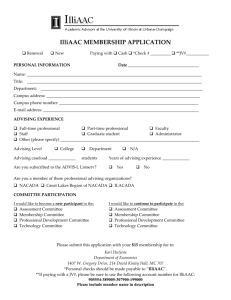

advertisement