Clients` Perceptions of the Therapeutic Relationship and Its Role In

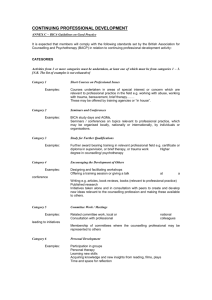

advertisement