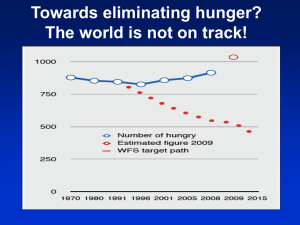

WIDER RESEARCH FOR ACTION-1 Hunger and Entitlements

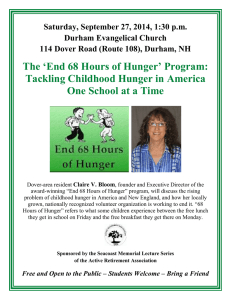

advertisement