Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18

advertisement

![Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/018637782_1-8c6fe85b50a9490b63f20ac864659582-768x994.png)

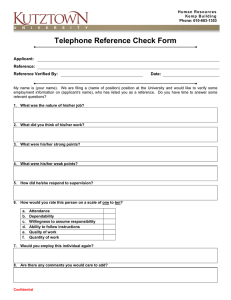

Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18 Augus... http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/cth/AATA/2005/789... 1 of 20 [Home] [Databases] [WorldLII] [Search] [Feedback] Administrative Appeals Tribunal of Australia You are here: AustLII >> Databases >> Administrative Appeals Tribunal of Australia >> 2005 >> [2005] AATA 789 [Database Search] [Name Search] [Recent Decisions] [Noteup] [Download] [Context] [No Context] [Help] Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18 August 2005) [AustLII] Administrative Appeals Tribunal [Index] [Search] [Download] [Help] Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18 August 2005) Last Updated: 24 August 2005 2005_78900.jpg Administrative Appeals Tribunal DECISION AND REASONS FOR DECISION [2005] AATA 789 ADMINISTRATIVE APPEALS TRIBUNAL ) ) No N2004/1368 GENERAL ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISION Re ) Reha Ekinci 1/07/2014 12:22 PM Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18 Augus... http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/cth/AATA/2005/789... 2 of 20 Applicant And Civil Aviation Safety Authority Respondent DECISION Tribunal Professor GD Walker, Deputy President Date 18 August 2005 Place Sydney Decision The decision under review must be affirmed. .............................................. Professor GD Walker Deputy President CATCHWORDS CIVIL AVIATION SAFETY AUTHORITY – refusal of aircraft maintenance engineer’s licence – applicant failed to pass the necessary examinations and meet the experience requirements specified in the CAO – examination of the applicant’s Schedule of Experience and associated documentation – examination of the requirements of the Civil Aviation Orders – examination of the issue of bias by CASA officials – comparison of the hours of experience requirements and the hours which can be demonstrated by the applicant – examination of whether the applicant made a false and misleading statement to CASA in respect of the verification of his work – whether the applicant is a fit and proper person to perform the functions and duties of a licence holder – found that there was sufficient evidence to establish four of the ten categories required but insufficient evidence to establish that he had accumulated the required experience in the other six out of ten categories – found insufficient evidence to establish he had the necessary experience in group 1 engines – held that there was insufficient evidence to prove he was not a fit and proper person to hold a licence – decision under review is affirmed. Civil Aviation Act 1988 s 20AB Civil Aviation Regulations 1988 s 31 Civil Aviation Orders Part 100 ss 100.90, 100.92 Jones v Dunkel [1959] HCA 8; (1959) 101 CLR 298 REASONS FOR DECISION 18 August 2005 Professor GD Walker, Deputy President Summary 1. Mr Reha Ekinci , who is aged 41, applied for the issue of an aircraft maintenance engineers licence ("AME licence"), in the engine category and a group 1 rating, under the Civil Aviation Orders. 2. A delegate of the respondent, the Civil Aviation Safety Authority ("CASA") refused Ekinci ’s application on the basis that the applicant did not meet the Mr necessary experience requirements specified in paragraph 65.31 of s 100.92 of the 1/07/2014 12:22 PM Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18 Augus... http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/cth/AATA/2005/789... 3 of 20 Civil Aviation Orders. That is the decision to be reviewed by the tribunal. Background 3. The applicant, Mr Ekinci , was born on 19 April 1964 and is aged 41. He is chief pilot and maintenance training officer for Air Combat Australia Pty Ltd situated at Narellan, New South Wales. He has been flying since 1982 and has owned 17 aircraft. 4. On 1 June 2004, Mr Ekinci applied for the issue of an aircraft maintenance engineers licence ("AME licence") in the engine category and group 1 rating (T p21), piston engines and associated systems other than those in groups 3 and 21. He also lodged with his application a schedule of experience ("SoE") (T pp24-73). On 20 July 2004, the acting section head, maintenance personnel standards section of CASA, advised Mr Ekinci that he had assessed his SoE and that due to the lack of certainty of the verification of the tasks recorded in his SoE, he was required to provide further information as to the completion of tasks listed by the acting section head (T pp74-86). 5. On 30 July 2004, Mr Ekinci telephoned the acting section head, maintenance personnel standards, and was advised that he would receive no guidance in respect of the results of his assessments until he had provided the written information sought (T supplied the information as requested by p87). On 17 August 2004, Mr Ekinci CASA (T p88). On 28 September 2004, he telephoned the acting section head, maintenance personnel standards, and was informed that a number of irregularities had been identified in his application and that the matter was being referred to the Office of Legal Counsel, CASA, for review (T p108). 6. On 13 October 2004, the section head, maintenance personnel standards, CASA, informed Mr Ekinci that his application for a LAME licence, engine category, group 1 rating, was refused on the grounds that he failed to satisfy CASA that he had (a) adequate appropriately verified experience in the maintenance of aircraft engines covered by a engines group 1 rating; (b) four years of general aircraft maintenance experience; and (c) two years of engine maintenance experience. He was informed that CASA had concerns that (T p5): The generic descriptions, imprecise/grouped dates, grouping of tasks, contradicted entries and unsubstantiated entries in the record in your SoE and the incorrect statements made on other occasions cause CASA to doubt the veracity of these entries and to be concerned whether you are a fit & proper person to hold an AME Licence. 7. On 20 October 2004, Mr Ekinci lodged an application for a review of that decision by the tribunal. 8. At the hearing, Mr Ekinci appeared in person and the respondent was represented by Farid Assaf, of counsel, instructed by Garth Cartledge, legal advocate, CASA. The evidence before the tribunal comprised the documents produced pursuant to s 37 of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act 1975 ("the T Documents"), consisting of two volumes taken collectively into evidence as Exhibit R1, together with evidence presented by the parties at the hearing. For the applicant, oral evidence was given in person by Mr Ray Ekinci , Mr David Dent, Mr Trevor Merton and Mr Eric Edwards. A further witness also gave oral evidence for the applicant, his identity being protected from publication by an order made under s 35(2) of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act 1975. He is referred to in this decision as "CD" (not his real initials). For the respondent, Mr Keith Johnston and Mr Derek Hoffmeister gave oral evidence in person. Relevant Law and Policy 1/07/2014 12:22 PM Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18 Augus... http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/cth/AATA/2005/789... 4 of 20 9. Section 20AB of the Civil Aviation Act 1988 ("the Act") prescribes that a person must not carry out maintenance on an Australian aircraft if the person is not permitted by or under the regulations to carry out that maintenance. At the date of the decision, the licensing procedure was set out in regulation 31 of the Civil Aviation Regulations 1988, which provides that a qualified person may apply to CASA for the issue of an aircraft maintenance engineer licence. Regulation 31(4) states: (4) In this regulation, qualified person means a person who: (a) has attained the age of 21 years; and (b) satisfies CASA that he or she possesses such knowledge as CASA requires of: (i) the principles of flight of aircraft; (ii) the assembly, functioning and principles of construction of, and the methods and procedures for the maintenance of, those parts of an aircraft that CASA considers relevant having regard to the licence sought; and (iii) these regulations and the Civil Aviation Orders; and (c) satisfies CASA that he or she has had such practical experience of the duties performed by a holder of the licence sought as CASA requires and directs in Civil Aviation Orders; and (d) satisfies CASA that he or she is not suffering from any disability likely to affect his technical skill or judgment; and (da) satisfies CASA that he or she possesses sufficient knowledge of the English language to carry out safely the duties required to be performed by a holder of the licence; and (e) has passed such examinations as CASA requires to be passed by an applicant for the licence sought. 10. The relevant provisions in the Civil Aviation Orders (CAO) are part 100, s 100.90 Administration and Procedure – Aircraft Maintenance Engineer Licences – General Requirements, which provides that "Except where otherwise approved or directed by the Authority, this Section of Civil Aviation Orders specifies the requirements under regulation 31 of the Civil Aviation Regulations for the grant or renewal of aircraft maintenance engineer licences" and s 100.92 Administration and Procedure – Aircraft Maintenance Engineer Licences – Category Engines, which provides that "Except where otherwise approved or directed by the Authority, this Section of CAOs applies to the requirements for the grant of an aircraft maintenance engineer licence in category engines and for the grant of additional ratings to a licence in this category". 11. Section 100.90 subsection 6 of CAO 100 states: 6.1 – A licence may be granted to a person who complies with the following requirements: (c) has passed the examinations and met the experience requirements specified in CAO Sections 100.91 to 100.95 as applicable; 12. Section 100.90 subsection 3 of CAO 100 sets out the parts of an aircraft which constitute the engine category and the privileges of the category in relation to engine running, maintenance, certification of electrical maintenance, instruments, radio and 1/07/2014 12:22 PM Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18 Augus... http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/cth/AATA/2005/789... 5 of 20 certification of maintenance on the airframe (T pp110, 113-114). 13. Section 100.92 subsection 3 of the CAO provides that a Group 1 rating refers to: Piston engines and associated engine systems in aeroplanes and airships, other than those classified in Group 3 and Group 21. 14. Subsection 5 of s 100.92 of CAO Part 100 sets out the experience requirements for examinations, grant of a licence or endorsement of a rating. Subsection 5.3 states: 5.3 - The minimum experience required for the grant of a licence is four years aircraft maintenance or aircraft component maintenance including: (a) two years aircraft maintenance experience in category engines; and (b) practical experience in the group or type for which a rating is sought, to the scope and depth indicated in the relevant Schedule of Experience issued by the Authority, or other approved documents. 15. The instructions for the relevant Schedule of Experience for category engines group 1 requires an applicant to provide evidence of work performed in 10 different areas of maintenance practice. It is the responsibility of the applicant to have each entry verified by (a) a licensed aircraft maintenance engineer (LAME) who has certified for the maintenance, or (b) a person appointed by a certificate of approval holder who has certified and supervised the work. This is to ensure that the applicant has satisfactorily completed the task, together with others completed the task, observed the task or carried out/received maintenance simulator training on the task (T pp125-127). The issues 16. The issue for decision is whether the applicant has satisfied the statutory requirements for the grant of an aircraft maintenance engineer’s licence. The evidence and submissions relevant to that issue fell broadly into three parts: (i) the question of alleged CASA bias and its effect on the licence application (ii) the schedule of experience and (iii) the other grounds for rejecting the licence application. The hearing – particular aspects 17. At the hearing Mr Ekinci appeared in person. Any applicant has a perfect right to present his or her own case, and the tribunal is bound in that event to make some concessions to the fact that most applicants are unaware of tribunal practice and Ekinci ’s extensive procedure. It might seem a little strange that a man with Mr business interests, both in Australia and overseas, could not arrange for a lawyer to represent him in an application that he considered important, but that was the situation and it had certain consequences. 18. First, Mr Ekinci maintained from beginning to end that the case was essentially about the bias that he claimed CASA displayed towards him, and much of his evidence related to that issue. The tribunal, however, has no jurisdiction to review administrative decisions for bias or on other judicial review grounds. Nevertheless, such questions can sometimes become tangentially relevant. In this case the evidence of alleged bias was admitted, over the respondent’s objection, because it had a bearing on the accuracy of some of the evidence of verification, notably that given 1/07/2014 12:22 PM Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18 Augus... http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/cth/AATA/2005/789... 6 of 20 by the witness CD. 19. Next, much of the applicant’s other evidence amounted to a general attack on CASA’s evaluation of his SoE for having allowed insufficient hours for the tasks he said he had performed or for disregarding his supplementary, mostly general, evidence of verification. He pointed to some specific examples of what he said were insufficient allowances or other matters, but made no comprehensive attempt to relate the evidence he adduced to the full range of the particular tasks he claimed to have performed. 20. Again, Mr Ekinci disregarded a specific direction at the hearing on 13 April 2005 to file and serve a witness statement in time for the resumed hearing on 20 June. He is an articulate man and is currently, he states, studying for a master’s degree in aviation administration. Drafting such a statement is well within his capabilities. At the resumed hearing he simply explained that the pressure of other business had prevented him from complying with the direction. That default contributed to the overall difficulty of ascertaining exactly what were the task hours and overall experience totals that he was claiming. 21. Because of the detail involved in the evaluation of SoE and the complexity that it entailed, I suggested to the parties at the hearing on 22 June that they might wish to prepare, in the four weeks available before the adjourned hearing date on which submissions would be presented, a written summary of their contentions, perhaps incorporating some form of tabulation showing how the evidence related to the individual disputed items in the SoE. The respondent accepted that invitation and lodged a summary of its contentions on 18 July. The applicant, however, did not and his submissions consisted largely of a reiteration of his claims of bias, of underestimation of hours and disregard of verification evidence. But, again, he offered no breakdown of precisely how the hours should, in his view, be calculated. He seemed to expect the tribunal to prepare a reconstructed SoE for him, which appeared to be the approach he had taken with CASA. 22. In that connection I asked the applicant if he had ever considered lodging an amended SoE setting out the hours and experience claimed in light of later inquiries, or whether he would now consider doing so. He replied only that he could not have lodged an amended SoE because CASA had it. As I pointed out at the time, it seemed odd that a man in his position would lodge an important application without keeping a copy of it. In any event his answer was incorrect – CASA had returned the applicant’s SoE to him under cover of its letter of 23 July 2004 (T p77). 23. Finally, the hearing was punctuated by outbursts of shouting and personal abuse (not all initiated by the applicant), despite my frequent admonitions to refrain from such behaviour. On one occasion it proved necessary to adjourn the proceedings temporarily in order to restore some measure of calm and order. One would think it should be possible to debate entries on a printed form in an objective and dispassionate manner, but in this case the maintenance of order was a continuing preoccupation that was not helpful to the clarification of the factual issues. The bias issue 24. Mr Ekinci stated that CASA officials, and in particular those based at the CASA office at Bankstown, New South Wales, had dealt with his application in a biased manner because of certain allegations made against him by a CASA officer at Bankstown, who will be referred to as AB (not his real initials). Because of the nature of the allegations against this person, the respondent applied for a s 35 confidentiality order to prohibit disclosure of his name. That order was made, and was expressed to include a witness in these proceedings, to be referred to as CD, who had allegedly been threatened by AB and asked for the protection of a s 35 order. 1/07/2014 12:22 PM Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18 Augus... http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/cth/AATA/2005/789... 7 of 20 25. Mr Ekinci believed that AB harboured a vindictive attitude towards him, and had influenced other CASA officers to adopt a similar attitude, as a result of certain confrontations between Mr Ekinci and AB. 26. The first of these episodes occurred when AB was chief engineer of an aviation service company at Bankstown. At that time the company had been offering 100 Ekinci took his maintenance work hourly inspections at a fixed price, and Mr to them. On two occasions AB had offered to sign off 100 hourly inspections without performing more than a perfunctory and superficial examination. Mr Ekinci had declined the offer on both occasions. Nevertheless, he became aware that AB had conducted shortened 100 hourly inspections of aircraft owned or operated by Mr Ekinci . 27. Some time after that, Mr Ekinci experienced an engine failure in an Airtourer inspected by AB, VH-BXD, in which part of a cylinder had broken off. He had no option but to execute a forced landing, with a student pilot on board, and shortly afterwards had a violent argument with AB in which he accused AB of nearly getting him killed and warned him in profane language not to do a "shonky" 100 hourly inspection on one of Mr Ekinci ’s planes again. 28. Subsequently he had another dispute with AB when he demanded that AB return some MiG parts that he had been seen removing without permission from an aircraft owned by a Mr Horace Treloar and which Mr Ekinci later purchased. The aircraft type in question is a jet fighter, originally designed in Germany during World War II (like its western adversary, the F-86 Sabre) and subsequently put into production in the Soviet Union under the name of Mikoyan Guryevich type 15, or MiG-15. AB admitted taking the parts and was prevailed upon to return them. 29. Next came a series of acts of alleged official misconduct that Mr Ekinci said AB had committed in his position as a CASA officer, after leaving the aviation industry. This culminated in a written complaint to the Australian Federal Police ("AFP") by Mr Ekinci alleging abuse of office by AB. The matter apparently did not proceed because the AFP received legal advice that certain evidence recorded on tape might be successfully challenged at a hearing because of the circumstances in which the recording was made (Exhibits A4, A5). 30. This series of confrontations, the applicant said, led to AB and another Bankstown officer using their positions in an attempt to sabotage his application for a LAME licence. He tendered a copy of an email from AB to Mr Rick McMaster, then executive manager of safety at CASA in Canberra (Exhibit A1). The email alleged that the witness referred to as CD had verified a substantial number of tasks listed on the applicant’s SoE under duress applied by the applicant and that a number of the SoE entries were dated before CD’s LAME licence was issued, or were otherwise incorrect. 31. The applicant called CD, who was a most reluctant witness. He declined to help prepare a witness statement and after his initial examination-in-chief he repeatedly refused to return for cross-examination by the respondent. It was not until after the district registrar of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal had written a formal letter to him explaining his legal obligation to appear that he did return, on the final day of the hearing. The applicant questioned CD about the circumstances in which he verified the original SoE, but later at CASA’s request reconsidered his verifications and withdrew a substantial number of them. He said he had been hesitant about signing the verifications in the first instance because many of the tasks had been performed some years before and he could not accurately recall whether he had supervised them without seeing the "job packages" for each operation, that is, the various log entries and job sheets. He denied that the applicant had threatened or intimidated him into signing the SoE, but did say that he felt under some pressure from him and for 1/07/2014 12:22 PM Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18 Augus... http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/cth/AATA/2005/789... 8 of 20 that reason proceeded to verify the SoE entries without seeing the job packages. 32. Subsequently CD wrote to CASA, to the attention of AB, the letter Exhibit A9 declaring that he had signed the applicant’s SoE under duress and had been scared and intimidated by him and feared severe repercussions for himself if the applicant were ever made aware of the letter’s contents. Under cross-examination by Mr Assaf, he said that he had written the letter because he had "panicked", fearing that his LAME licence "might go". He had been told that his file had been transferred from the Bankstown office, where it would normally be kept, to Canberra, and had feared that this was the prelude to some serious action by CASA. Asked whether the letter was true, he replied "yes and no" and that it "was true in a way", explaining that he signed it because he "had everyone on my back" and "didn’t want to lose my licence". In response to a question from the applicant, he admitted that AB had telephoned him and "might have discussed the SoE", that he did feel threatened because "there was pressure coming from everywhere, not just from [AB]". 33. CD did not deny hearing the applicant tell the respondent’s solicitor that CD felt threatened by AB. The applicant, CD admitted, had also told CD that he would not risk CD losing his licence. He had added, "Do what you have to do, ... " The applicant said in his evidence. CD had later given him a copy of the letter Exhibit 9 and had apologised for writing it, saying that he had done it to protect himself. 34. While admitting that he cooperated with Bankstown’s request to review his verifications partly in order to remain on good terms with CASA, CD maintained firmly that his revised verifications on the SoE as disclosed in the worksheets shown to him at the Bankstown office, were correct and that his original verifications had been "hasty". He did not deny that he might well have supervised more tasks in addition to those verified in the revised schedule, but said that he could not certify them without seeing the relevant files. 35. Another aspect of AB’s conduct showing bias against him, Mr Ekinci said, was revealed in a letter from CD to the applicant dated 12 June 2002 (T p89). It is a short but rather ambiguous letter, the full text of which is as follows: Dear Ray, We advise we have transferred the files you seek in accordance with [AB]’s instructions. I furnish you with the maintenance data, including calibration certification. I can not release the tooling as there is a dispute over money between you and Phil Onis. Regards, ... The applicant construed that letter as showing that AB had induced CD to transfer a number of job files from CD’s possession to the new company formed after the breakup of his business relationship with Phil Onis, in order to deny Mr Ekinci access to them. Those files, he said, recorded at least 250 hours of maintenance work he had performed under Peter Hoad’s supervision. 36. That is a possible interpretation, but it leaves open the question of what is meant by the words "I furnish you with the maintenance data, including calibration certification." Was this maintenance data from the transferred files, or some other body of data? The reference to calibration might mean it related to tools rather than aircraft. AB was not called as a witness and CD offered no help in clarifying the letter’s meaning, saying it was a long time ago and he could not remember where the files were. That was consistent with his general stated inability to recall the details of his discussions with AB, even when they clearly made a powerful impression on him. 37. The respondent submitted that the letter could only be interpreted as meaning that Ekinci (through AskDaily Pty Limited) the worksheets and other CD gave Mr information. In the absence of oral evidence from AB or CD that might clarify its meaning, however, I am unable to give that ambiguous communication any weight on 1/07/2014 12:22 PM Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18 Augus... http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/cth/AATA/2005/789... 9 of 20 either side of the case. The fact that it is dated June 2002, two years before the application was lodged, would also seem to reduce its relevance to these proceedings. 38. AB was seated at the back of the hearing room when CD was cross-examined and re-examined. The applicant surmised that he had been brought in by CASA as a form of implicit intimidation, to remind CD of possible adverse consequences if he were to reveal anything about the alleged threats made by AB. The applicant in his own evidence had testified that CD had told him that it was because of a telephoned threat from AB that he feared loss of his licence and said that he had given CD his word that he would not raise the question of AB’s threats unless CASA did. Another possible explanation for AB’s presence at that particular time, however, is that he knew his name might be mentioned in the course of CD’s testimony and wanted to be present to hear what was said about himself, a perfectly legitimate motive for attending (not that anyone needs a legitimate reason for attending a public hearing). At all events, there is no evidence whatever that CASA has attempted any reprisals against CD. Quite the contrary in fact – CD was recently granted a PT6A endorsement to his licence only two weeks after applying for it. 39. Mr Eric Edwards, principal inspector of maintenance personnel at CASA in Canberra, was called by the applicant, on summons, to give evidence. The applicant’s examination of Mr Edwards was plainly designed in part to elicit responses tending to show that the Canberra office had colluded with AB and one or more other persons at the Bankstown office in a plan to ensure that the applicant did not receive a LAME licence because he was seen as a whistleblower and a trouble-maker. It was clear that Mr Edwards was aware of the tensions between AB, and possibly other Bankstown officers, and the applicant, but nothing in his evidence suggested any bias or animus towards the applicant that might have influenced his handling of the application. Indeed, Mr Edwards had endeavoured to help the applicant to overcome the problem that some of his verifiers were deceased or overseas, advising him on alternative methods of attesting, such as statutory declarations, which can be acceptable in some circumstances. 40. The applicant’s cross-examination of Mr Keith Johnston, an airworthiness inspector at CASA central office in Canberra, also endeavoured to establish, among other things, the existence of a bias against the applicant that was manifested in Mr Johnston’s disregard of the statutory declarations and other alternative methods of verification when assessing the applicant’s SoE. The applicant’s aggressive questioning of Mr Johnston elicited no such evidence. The witness explained that the original SoE had been returned because there were doubts about some of the verifications, because many entries did not specify the aircraft type or date of the work and described the tasks only in general and unhelpful terms. CD had been asked to reconsider verifications because some of the entries he had originally verified bore dates earlier than the date on which CD had received his LAME licence. When the SoE had been returned to the department, Mr Johnston said that he had reassessed it over a period of several days, giving it a full review and taking into account the statutory declarations and other statements, as well as accepting some entries even if not verified at all. All items that were confirmed were accepted, and those not verified were for the most part rejected. 41. AB gave no evidence, and no explanation for his failure to do so was offered. He was clearly available, as he was seated in the hearing room while CD was under crossexamination on the fifth day and for some time afterwards. Applying the principle in Jones v Dunkel [1959] HCA 8; (1959) 101 CLR 298, I infer that the respondent considered that his evidence would not have been helpful to its case. 42. On the preponderance of probabilities it seems likely that AB did telephone CD about the applicant’s SoE, and that AB did threaten CD with loss of his LAME licence if he persisted in supporting Mr Ekinci ’s application. One or more 1/07/2014 12:22 PM Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18 Augus... http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/cth/AATA/2005/789... 10 of 20 other CASA officers based at Bankstown may have also been privy to that conduct. I find no evidence, however, to support the proposition that CASA’s evaluation of Mr Ekinci ’s application, and specifically his SoE, was in any way influenced or affected by any bias against the applicant. 43. The main relevance of the bias evidence was to the question of whether, as a result of that bias, CD had been pressured into withdrawing his verification for tasks that he had in fact supervised. I think it likely that AB’s threat was the main reason why CD reconsidered his verifications on the applicant’s SoE and withdrew those for which he was not shown a job sheet or other documentary corroboration. It is probable that some of those entries related to tasks that CD had in fact supervised and would have been prepared to verify if he had sighted the appropriate written records, but could not confidently certify otherwise. In that sense CD’s revised verifications are true and complete. Mr Ekinci did not challenge the revised verifications except to ask CD if the other claimed tasks were in fact performed and supervised. CD did not deny that, but said he could not certify tasks without seeing the documentary records. The schedule of experience 44. As Mr Johnston, a CASA airworthiness inspector based in Canberra, explained in his affidavit (Exhibit R6), in normal cases an applicant for an AME licence is a person who has been an apprentice or other employee in a full-time position in a maintenance organisation who is performing maintenance under the provision of a licensed aircraft maintenance engineer (LAME). Many of those people concurrently follow a course of theoretical study culminating in various theory examinations prescribed by CASA. Such a person also usually completes an SoE and has it verified by a LAME after completing each maintenance task. An SoE completed in that way is a contemporaneous record of the maintenance that the unlicensed person has performed under supervision. 45. Mr Ekinci did not follow that approach. As Mr Trevor Merton explained in his statutory declaration (Exhibit A2), the applicant has always had a policy of conducting as much maintenance as possible on his fleet of aeroplanes himself, under the supervision of qualified LAMEs, who have included Roy Coburn, Peter Hoad, Anthony Death and Tim O’Connor. He currently operates a fleet comprising two Airtrainers, two Yakolev 52s (with radial engines), one Piper Aerostar, one Ted Machen Superstar 700, one Enstrom F28 helicopter, one Learjet 24 XDR and two MiG-15 fighters. 46. Mr Ekinci lodged his application for a LAME licence, accompanied by what was claimed to be a statutory declaration by himself (T p23), explaining that Roy Coburn, with whom he had worked on VH-ALN, was deceased, and that Anthony Death was working in Saudi Arabia and unable to sign for the work he supervised, and that Peter Hoad, who supervised the tasks on VH-FWZ, AMX and BXD, was unwilling to assist with the application because of certain personal differences between them. That document (T p23) is not actually a statutory declaration, not having been properly witnessed. Mr Ekinci also attached a letter (T p91) from LAME Stan Ral describing particular tasks performed by Mr Ekinci under his supervision between 28 September 1992 and 26 June 1993 on VH-BXD, but without specifying the hours taken. He also stated that Mr Ekinci performed "several cylinder changes" and "several 100 hourly inspections on BXD under [his] supervision" but did not stipulate how many or the hours taken. Mr Ral also stated conducted two 100 hourly inspections that between 1991 and 1994 Mr Ekinci on VH-FWZ under his supervision, as well as other work on VH-FWZ, ALN and AMX, but with no hours or specific dates. 1/07/2014 12:22 PM Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18 Augus... http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/cth/AATA/2005/789... 11 of 20 47. Mr Johnston assessed the application and SoE, but concluded that many of the SoE entries did not provide a clear description of the task performed, were not verified properly or at all, in some instances were verified by the applicant himself, were verified by persons who did not hold an AME licence, were not substantiated by evidence or claimed excessive hours for task. CASA therefore wrote to the applicant on 20 July 2004 a letter (T pp74-77) indicating that verification from the LAMEs Death, Hoad and Hobson was required. It also required the applicant to "supply a correctly completed Statutory Declaration covering the statements you have made concerning verification of the SoE entries" (T p76). 48. Mr Johnston interpreted that passage being a request for a statutory declaration concerning the entries that the applicant had verified himself and the reasons he had done so, noting that "In any event, if such a statutory declaration were provided, it would not have been a substitute for proper verification of entries by the supervising LAME". I do not construe that sentence in that way. To me it seems to be a reference to the purported statutory declaration on T p23, mentioned above, describing the problems Mr Ekinci faced in obtaining verification from Messrs Death, Hoad and Coburn. 49. Mr Johnston commented that "Mr Ekinci appears to have construed the letter in terms that enabled him to provide statutory declarations from other persons as a substitute to verification of individual entries in the SoE". That may be so, but it is also true that in his oral evidence Mr Eric Edwards, of the CASA Canberra office, Ekinci on alternative methods of attesting where said he had advised Mr certain verifiers were deceased or overseas, including the lodgement of statutory declarations, which were acceptable in some circumstances, although use of the printed forms was preferred for the sake of uniformity of treatment and evaluation. 50. At all events, the applicant proceeded to obtain statutory declarations from Kenneth Mogus (T p103) and Timothy O’Connor (T p105). Mr Mogus declared that he had supervised Mr Ekinci carrying out 100 hourly inspections and other maintenance and rectification work on FWZ, BXD, AMX and HJU between 30 June 1994 and 30 June 2002. As that maintenance was all in the instrument and electrical categories, it was not relevant to the requirement for 250 hours of scheduled maintenance on group 1 piston engines. Mr Mogus also declared that he also "observed Reha Ekinci being supervised by various licensed aircraft engineers while carrying out maintenance in the engine & airframe categories on the above mentioned aircraft". Mr O’Connor’s statutory declaration stated that the applicant had assisted him in performing a 100 hourly inspection of VH-AMX on 10 July 1996. 51. Mr Ekinci delivered the above statutory declarations and letters to Mr Edwards at the Canberra CASA office on 19 August 2004, together with a large number of job sheets, six years of MiG maintenance schedules for VH-EKI and VH-REH, and copies of log book pages for AMX, JEN, WGK, RNV and CAU (T pp107, 310-373). Mr Johnston said that he took all that material into account when conducting his re-evaluation of the SoE. If that material confirmed a specific task listed in the SoE, the item was allowed, but if it did not, the item was not allowed. 52. Nor had he allowed work done on the MiG fighters in the electrical and instrument section, explaining that CASA looked for experience of work on a range of group 1 aircraft, and the MiG was not in group 1. He conceded that the work of performing magnetic compass swings and inspecting electrical cabling on a MiG would be similar to that required on other aircraft, but said that those categories were too narrow. Evaluators would usually reject a SoE if the work done was only on one aircraft type, or else they would limit certification to that type. Besides, the instrument systems on turbine aircraft were often materially different from those in machines with reciprocating engines. 1/07/2014 12:22 PM Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18 Augus... http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/cth/AATA/2005/789... 12 of 20 53. Following his review of the SoE with the new evidence, Mr Johnston again reached the conclusion that the evidence produced was insufficient to justify the issue of a license. The applicant had not established that he had accumulated four years’ experience in aircraft maintenance and two years on engines, and had still not sufficient experience on group 1 engines. Mr Ekinci ’s SoE had been particularly difficult to assess because the form requires information about aircraft type, job number, date of completion and description of the work done. In many instances the applicant had not supplied that information. 54. Despite the fact that the applicant held an LIS-2 maintenance authority covering historic and ex-military aircraft, he was not authorised to verify his own work on those types or on any others, Mr Johnston said. Mr Ekinci disputed that proposition. He stated, and this part of his evidence was unchallenged, that he is a recognized expert on the MiG-15 and conducts a course on east European jet aircraft. He was appointed by CASA to be its expert witness at an inquest into a MiG accident. He has flown, and still flies, the MiGs that he owns and maintains, without any maintenance-related incident to date. In his view he should be able to verify his own work on the MiGs at least. CASA contends, however, that the legislation does not permit self-verification in any circumstances. I will return to that legal proposition later. 55. Mr Johnston was adamant that wherever the new material confirmed a specific job listed in the SoE, he allowed it. There seemed to be some exceptions to that, however. The scheduled inspection on VH-AMX on 10 July 1996 (Exhibit R6 p21) was not allowed any time on the ground that it was not verified, but in fact it does appear to be verified by Mr O’Connor (T p105). A scheduled inspection on the same aircraft on 16 August 1998 appears to have been verified by Anthony Death, as is the scheduled maintenance on Airtourer VH-RNV on 14 August 1998. Mr Death’s letter also appears to verify the scheduled maintenance performed on AMX on 9 June 1999. I will return to those exceptions later. 56. Mr Derek Hoffmeister, chief engineer of Vee H Aviation Pty Limited in Canberra, agreed that the SoE lacked the kind of detail needed to enable it to be accurately assessed. It did not, for example, indicate whether a "scheduled inspection" was a 100 hourly or a 50 hourly (as with VH-FWZ), in some instances only the registration letters were given, not the aircraft type, and some gave neither registration nor type. The description of some work performed on VH-ALN as "fuel system and fuel tank and pressure systems" left it uncertain exactly what kind of work was performed on the fuel system, and the entry recording the cleaning of the fuel system on VH-WGK (job 37) did not make it clear whether the fuel system had been completely disassembled. If it had, there would have been a large increase in the number of hours needed. Mr Hoffmeister confirmed that the checking of instruments and electrical systems on a turbine aircraft would be helpful but insufficient because there are differences between those systems in jet aircraft as against those with piston engines. In piston-engined aircraft the starter and alternator are separate, but in a jet they are one. In a piston-engined aircraft, gyro suction can be generated by a pump, but in a jet the vacuum is taken off the engine. 57. The respondent also took issue with the times the applicant claimed for various classes of work. In relation to scheduled maintenance, Mr Johnson estimated that it would take no more than four to five hours to perform the 100 hourly periodical inspection of a group 1 piston engine (the rectification of defects is recorded separately). The applicant had claimed up to 17 hours for a periodic inspection of an engine. Mr Johnston considered that excessive, but allowed six hours for each engine of any type inspected at a periodic inspection. The respondent’s other witness, however, Mr Derek Hoffmeister, estimated eight hours each for a wide variety of engine types. 1/07/2014 12:22 PM Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18 Augus... http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/cth/AATA/2005/789... 13 of 20 58. Mr David Dent, chief engineer of Dent Aviation at Camden Airport, stated that a basic four-cylinder engine could take between eight and 10 hours to inspect as part of a scheduled inspection. That assumed a carburettor fuel system and normal aspiration. An hour would have to be added if it were fuel injected and an extra hour and a half to two hours for an inverted oil system. A four-cylinder engine could thus take up to 12 hours to inspect, depending also on the ease of access of the installation in the particular aeroplane. A non-complex six-cylinder engine would take between 12 and 14 hours, but added complexities such as supercharging, turbo-charging, gearing or pressure carburettors would all add time to that basic time allowance. The type of installation on the particular aeroplane can also require extra time. 59. An Aero Commander 560E, a PA60 Aerostar or a Ted Machan Superstar 602P/700 all fall into the complex engine category requiring 15 hours for inspection, as would the powerplants of the Yak 52 and Piper PA23-250 Aztec. Mr Dent’s statement (Exhibit A2) attached a copy of the Pacific Aviation Periodic Schedule for New Aircraft. Until recently Pacific Aviation was the Piper agent in the Asia-Pacific region. The engine inspection schedule quoted for a normally aspirated PA60 Aerostar, including electrical checks, is 30 hours. It would therefore not be unreasonable, Mr Dent said, to expect 17 to 18 hours for an inspection on a used or ageing Superstar or Aero Commander engine. Mr Dent pointed out that the chart relates to new aircraft, but today most aircraft serviced are old. (It is well known that light or general aviation aircraft manufacturing was almost annihilated in the 1970s and 1980s by product liability litigation and legislation: see Walker, The Rule of Law: Foundation of Constitutional Democracy (1988), pp 376, 459. Consequently, most general aviation aircraft in service today are quite old.) CASA itself states in its Ageing Aircraft Program materials that the inspection of older engines takes longer. 60. The respondent criticised Mr Dent’s evidence on the ground that neither he nor the applicant defined what is meant by a "basic four-cylinder engine" or a "non-complex six-cylinder engine" or a "more complex six-cylinder engine". It is reasonably clear from the evidence, however, that by a basic four-cylinder engine Mr Dent intended a normally aspirated engine with carburettor, no inverted oil system and a reasonably straightforward installation. The respondent also pointed out that the applicant had not established the types of aircraft listed in the SoE, but that is not a substantial issue when one considers that Mr Johnston on behalf of CASA estimated an average of six hours for all engines inspected at a periodic inspection. 61. The applicant also relied on the evidence of Trevor Merton, who until July 2000 was the fleet senior check captain for the Qantas Airways Boeing 747 fleet. He is a qualified marine and aeronautical engineer and a qualified test pilot, having undertaken a test pilot course at the National Test Pilot school in Mojave, California. He is also senior vice president of Precision Aero Engineering, a company manufacturing aircraft engines. He does not hold an AME licence but is qualified to design aircraft engines. At the hearing he said that in his opinion the times the applicant had given for periodic inspections were overestimated by about 10 per cent, but he had considerably underestimated the time taken for his rectification work. 62. In his view, the times specified and accepted by CASA in relation to Mr Ekinci ’s application were not realistic. A minimum of eight hours per engine would be required, and complex piston engines such as the ones fitted to the Superstar would take two men approximately 12 hours each (ie 24 hours in total) to inspect. The Aero Commander would take approximately the same amount of time. The Piper Aztec takes approximately four man hours merely to remove and refit the engine cowlings before inspecting the engines, and the cowlings count as part of the inspection. 1/07/2014 12:22 PM Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18 Augus... http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/cth/AATA/2005/789... 14 of 20 63. The respondent stressed that Mr Merton is not a LAME. He has, however inspected about 12 different piston aircraft types and performed about 25 to 30 inspections over the last 10 years. His role in such cases was to assist, not to take primary responsibility for the inspection. In the early 1970s he had worked for a Melbourne company using Commanders on ambulance and survey work. In that capacity he had gained field experience on 100 hourly and 50 hourly inspections. He had spent hundreds of hours assisting Mr Ekinci to conduct both scheduled and unscheduled maintenance. He had assisted and observed him conduct at least 21 inspections, which he estimated would have taken well over 800 hours for Mr Ekinci to complete, on piston-engined aircraft. While he was not present the whole time when the applicant was inspecting such aircraft, he was usually somewhere else in the same hangar or workshop and knew Mr Ekinci was working full-time on the engine. 64. Mr Merton concluded by saying that the ultimate test of maintenance is satisfactory operation. He had never experienced a significant problem with any aircraft he had flown that had been maintained by Mr Ekinci , except where a particular component, such as an alternator, had failed. He had been flying aircraft maintained by the applicant for approximately 14 years. 65. Witness CD gave evidence that inspecting a four-cylinder Lycoming would usually take eight hours. He said he could do a six-cylinder engine in a day. A geared turbo Lycoming would need 20 hours for the inspection alone. The respondent did not challenge CD’s time estimates. 66. The evidence establishes, in my view, that on average a minimum of eight hours are required to inspect almost any piston engine in service today, and that up to 17 or 18 hours for a complex six-cylinder engine is not excessive, depending on the convenience of the installation. 67. Mr Johnston concluded that the applicant had only demonstrated 114 hours (the respondent conceded that this should actually read 180 hours) of the required 250 hours for scheduled maintenance. That was based on his method of not allowing time for entries that were not verified and for allowing six hours for an engine inspection where there was satisfactory verification. 68. The applicant disputed Mr Johnston’s approach to verification and said his allowance of six hours per engine was inadequate. He did not, however, suggest a total figure for the hours that would be allowed if a correct approach were adopted. 69. The respondent contended that even if Mr Johnston was wrong (which it denied) and the tribunal were to accept eight hours as a reasonable time to perform a scheduled 100 hourly inspection (CASA submitted that would be the maximum allowable for all engine types), the applicant would still not achieve the required minimum of 250 hours because CASA had allowed 30 engine inspections, which would total 240 hours at eight hours each. 70. Witness CD did not deny that the applicant had performed other work under his supervision that he was not prepared to verify, but took the justifiable position that he would not verify any work without seeing the appropriate records. 71. There remain the four scheduled inspections verified by O’Connor and Death referred to above. The respondent contends that Mr O’Connor’s statutory declaration assisted me" in deserves no weight because it states that "Mr Ekinci performing the inspection, rather than saying that Mr Ekinci did any maintenance which Mr O’Connor supervised. In light of the other evidence from Mr Merton, Mr Mogus, and Mr Ral about the scope and extent of the inspection and maintenance work carried out by the applicant, I think Mr O’Connor’s particular choice of words is not significant and that he can be taken to have supervised Mr Ekinci on that occasion. 1/07/2014 12:22 PM Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18 Augus... http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/cth/AATA/2005/789... 15 of 20 72. Of Mr Death’s letter stating that he supervised the applicant performing the work signed out by him in the log books for VH-RHV and AMX, the respondent states that it is unacceptable, because no further detail about that work has been provided or identified by the applicant. If one reads that statement in the context of the statement earlier in the same letter that Mr Death was AskDaily’s chief engineer between 1998 and 2000, it can reasonably be concluded that the periodic inspections claimed by Mr Ekinci were supervised by Mr Death. Taking into account those four inspections at eight hours each would give the applicant a total of 272 hours of scheduled maintenance work, even on the rather conservative assumption of eight hours per engine of any type. 73. The SoE for the category engines group 1 sets out the "scope and depth" of the experience required by CASA. It lists 10 areas of practical experience required to be demonstrated by an applicant for an AME licence (T pp29-30), namely: Area Scheduled maintenance Engine installation Fuel metering and control (carburettor system) Fuel metering and control (injection system) Ignition and starting systems Propeller and propeller control Electrical systems Instrument systems Engine run/adjustment Mechanical maintenance Requirement 250 hours 40 hours 50 hours 50 hours 45 hours 30 hours 25 hours 25 hours, including a minimum of 4 compass calibrations 15 engine runs 75 hours 74. Scheduled maintenance has been dealt with. Of the nine remaining areas of practical experience required to be demonstrated by an applicant for an AME licence, the respondent is satisfied that the applicant has met the requirements for three of them: engine installation, fuel metering and control (carburettor system) and mechanical maintenance. 75. As regards fuel metering and control (injection system), one entry that was validly certified by CD as LAME was rejected because no details of the aircraft registration, aircraft type, date or nature of the inspection were given. In relation to another entry correctly verified by CD, the respondent allowed only 30 per cent of the total time claimed because a substantial part of the work involved airframe tasks connected with removing the system. In relation to the other entries, CD withdrew his verification. Job 70 on VH-HJU was also verified by another LAME, but the respondent rejected that entry because no explanation for the existence of two verifications was given, and the entry was not dated. Even if the 15 hours claimed for this task were allowed, when added to the 30 hours accepted, it would still produce a total short of the 50 hours required. 76. The respondent rejected the whole of the 82 hours claimed in relation to ignition and starting systems because witness CD withdrew his verification, and there were no dates and no supporting maintenance documents. 77. In relation to propeller and propeller controls, the respondent allowed 22 hours, as against the 30 hours required, because CD withdrew his verification of some entries and the applicant verified some of his own work on other tasks. Whatever room for Ekinci himself verifying debate there may be about the appropriateness of Mr 1/07/2014 12:22 PM Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18 Augus... http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/cth/AATA/2005/789... 16 of 20 tasks carried out on the MiGs, there can be no such doubt in relation to work on the propeller systems in piston-engined aircraft. 78. Again, the respondent disallowed most of the hours claimed in relation to electrical systems, because CD withdrew his verifications for 120 hours of tasks and the applicant verified his own work for most of the remaining hours claimed. The evidence showed that some of the electrical work Mr Ekinci performed on the MiGs could be regarded as relevant to the application, but only to a limited extent, as there are differences in the electrical systems of jets and piston engined aircraft, and in any event, the respondent expects applicants to show experience across a range of aircraft types. The applicant needed only a further 13 hours to satisfy this category and it is possible that relevant work on the MiGs might have been sufficient, but the information supplied provides no basis for determining what the relevant work on the MiGs might have been. Further, it is unacceptable for the applicant to verify his own work on piston-engined aircraft. 79. The applicant said in evidence that a CASA officer based at Bankstown, Mr Gary Arnold, had told him that he could verify the electrical systems work himself. Mr Arnold was not called to give evidence for the respondent and no explanation was offered for his absence. Under the principle in Jones v Dunkel (supra), I conclude that it is likely that Mr Arnold did say that the applicant could certify the electrical work himself, or at least those parts of it performed on MiGs. Even so, that opinion could not bind CASA and, subject to what I have said about the work performed on the MiGs, I think Mr Johnston was justified in not accepting the applicant’s own verifications. 80. The respondent also rejected most of the hours claimed in the instrument systems category because in most cases no aircraft or dates were specified, witness CD withdrew one of his verifications and in relation to the others the applicant had verified his own work. That included 11 hours in respect of the two MiGs, VH-EKI and REH. They consisted of 11 inspections, all entailing compass swings. No supporting maintenance documents were submitted. Even if those hours were allowed, and were taken to include the required minimum of four compass swings (calibrations), the applicant would still be well short of the 25 hours required. The applicant repeatedly said that the six hours claimed on T p154 had not been credited to him, although the tasks had been verified by Mr Ral. That is not correct. Those hours were allowed in full, even though no dates or aircraft types had been specified. 81. Under the engine run/adjustment category, applicants are required to demonstrate that they have carried out at least 15 runs. The respondent allowed the runs supervised by Messrs Ral and Hobson, but not those purportedly verified by the applicant himself or the withdrawn verifications of CD. None of the rejected runs were performed on MiGs. 82. In his reply to CASA’s submissions about his failure to demonstrate the required experience in the six remaining categories, the applicant contended that all six formed part of the scheduled maintenance process. He also reiterated the difficulties he faced in obtaining access to the recovery records when one of the verifying LAMEs was deceased and two were out of business. Neither of those points advances his case. The hours required in those categories are plainly intended to be additional to the hours required in scheduled maintenance. The problems the applicant faces in securing the records of his work are no doubt real, but the fact remains that the onus is on a person seeking a licence to produce the required evidence. 83. As was noted above, the applicant was also required to demonstrate a minimum of four years’ aircraft maintenance experience, including two years on engines and practical experience in the group or type for which a rating is sought. 1/07/2014 12:22 PM Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18 Augus... http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/cth/AATA/2005/789... 17 of 20 84. The applicant gave evidence that he has met those requirements, indeed that he has worked in aircraft maintenance for 17 years, and has accumulated two and a half years’ experience in piston engines. He did not, however, attempt a detailed breakdown to show how his experience in fact equals or exceeds the required totals. Mr Merton said he observed the applicant perform 21 aircraft (not simply engine) inspections, totalling 800 hours. As the respondent points out, two years at seven hours per day equals 728 hours. 85. The respondent contended that Mr Ekinci ’s extensive experience as a pilot and his substantial business interests in Australia and overseas meant that he was unable to devote a substantial amount of time to the required types of aircraft maintenance. Mr Ekinci said that his other business interests were managed by others, and took very little of his own time. Even apart from that, I think there is a real possibility that the applicant has indeed accumulated or exceeded the levels of total experience that applicants are to demonstrate, but his evidence on that point is too general to allow the tribunal to make a finding to that effect when it is disputed by the respondent. Without some identification of the actual periods during which the applicant attests that he was engaged in piston engine maintenance full time, or for a stated proportion of his time, there is no proper foundation for a finding of fact in his favour. The other grounds for rejecting the application 86. The respondent argued that even if it had erred in finding that the applicant had not demonstrated the requisite experience (which it denies), an alternative basis on which CASA or the tribunal should refuse to grant the applicant a licence is that the applicant made, in or in connection with an application, a statement that was false or misleading in a material particular (see CAR 264). 87. The respondent referred to CD’s letter to AB of 7 July 2004 (Exhibit A9) stating that the applicant had pressured CD to signing the SoE despite CD’s expressed wish to see the worksheets and other records before endorsing the applicant’s various claims. That letter led to the CASA office of legal counsel writing to CD its letter dated 25 January 2005 asking CD to verify the SoE in light of the worksheets relating to various maintenance tasks CD had previously certified (Exhibit R6 Annexure A). CD returned the SoE to CASA, having made notations that some tasks he had previously verified were supervised, some were not supervised by him and of some he had no recollection or knowledge. The respondent contends that as CD now states that he Ekinci for some of the items, Mr Ekinci must have did not supervise Mr submitted to CASA an SoE that was false or misleading in a material particular. 88. The applicant replied in his evidence that he did not ask CD to sign entries for tasks he had not in fact supervised. He only wanted CD’s verification for the work he had actually supervised, and CD had made a mistake by initialling the other entries. Further, CD had said that AB had threatened him with loss of his LAME licence if he assisted the applicant any more. CD had told him that he had written the letter Exhibit A9 because he had said his bread and butter were on the line and he had no choice but to cooperate with AB. The applicant had said to him "Do what you have to do ...". CD had later given him a copy of the letter and had apologised for writing it, but said that he did it to protect himself. 89. The respondent pointed out that CD initially gave evidence-in-chief after he was called by the applicant. The applicant asked him no questions about the alleged CASA threats, nor did he attack the reverified SoE. While it was unusual for CD to refuse to return to the tribunal to be cross-examined by CASA, the respondent said, no inference could be drawn from a failure to comply with a summons to give evidence. The applicant, however, explained his failure to question CD about the 1/07/2014 12:22 PM Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18 Augus... http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/cth/AATA/2005/789... 18 of 20 alleged threats by saying he had given his word to CD that he would not raise the matter of threats unless CASA did so first, as CD was afraid of reprisals from CASA if he said anything about the matter. 90. As I have said above, nothing in the evidence suggests that CASA has sought to exact reprisals from CD for any assistance he may have given to the applicant. Indeed, after his evidence-in-chief, and before the resumed hearing, CD applied for a PT6A endorsement to his licence and received it only two weeks later, on 27 May 2005. I also do not think that any person at CASA’s Canberra head office made or authorised any threats against CD. At the same time, however, I have concluded that AB probably did threaten CD in the manner alleged. It should also be noted that in cross-examination CD did not deny that he probably had supervised the applicant performing other maintenance tasks on piston engines in group 1, simply stating that he had withdrawn his verification from any tasks that were not supported by documentary evidence. 91. Mr Ekinci said in his evidence, as I have also noted above, that he did not ask CD to verify items that he had not supervised, whether they were performed before he obtained his licence or for other reasons, and that CD had simply made a mistake by initialling those entries. The respondent did not invite CD to comment on that part of the applicant’s evidence. The applicant does concede, however, that he should have checked all of CD’s original verifications on the SoE. CAR 264 is a provision of strict liability requiring no proof of intention to mislead or deceive. That ground for refusing the licence must therefore be taken to be made out. 92. Another basis on which CASA or the tribunal could properly refuse a licence, the respondent contended, is that the applicant is not a fit and proper person to have the responsibilities and exercise and perform the functions and duties of a holder of the licence for which the application was made (see CAR 264(1)(c)(ii)). The first ground on which the respondent bases that contention is that the applicant does not have the relevant experience of a LAME with engine rating group 1. That fact, however, is more properly considered under CAR 264(1)(a). The respondent’s second ground is that the applicant is not a fit and proper person because he made false and misleading statements to CASA. While the making of a false or misleading statement in a material particular is a matter of strict liability under CAR 264(1)(b), I think that under paragraph (c)(ii) some element of intention or recklessness in making the misleading statement is required. I also consider that the applicant’s explanation in relation to that aspect of the case is acceptable. 93. The applicant also states, and the respondent did not dispute, that no aircraft maintained by him has ever crashed or suffered an in-flight engine failure. The evidence of Mr Merton, a highly distinguished aviator, supports the view that Mr Ekinci , whatever the shortcomings in his SoE documentation, is a conscientious and reliable maintenance engineer. 94. Consequently there is no basis for finding that he is not a fit and proper person within the meaning of CAR 264(1)(c)(ii). Application of the Law and Findings of Fact 95. The issue for the tribunal to determine is whether Mr Ekinci satisfies the experience requirements specified in paragraph 5.3 of s 100.92 of the Civil Aviation Orders to enable him to be granted an aircraft maintenance engineer’s licence (AME). The CAO requires the applicant to satisfy CASA that he has had four years’ full-time experience in aircraft maintenance and two years’ full-time experience performing maintenance on engines, and that he has had practical experience in 10 areas of maintenance practice. 1/07/2014 12:22 PM Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18 Augus... http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/cth/AATA/2005/789... 19 of 20 96. In its Statement of Facts and Contentions (Exhibit R2), the respondent summarised CASA’s assessment of the practical experience that the applicant has had: Task Area Required Hours Scheduled maintenance Engine installation Fuel Metering and Control (Carburettor) Fuel Metering and Control (Injection) Ignition and Starting Propeller and Propeller Control Electrical Systems Instrument Systems and at least 4 compass calibrations Engine Run/Adjustment Mechanical Maintenance 250 40 50 Hours assessed by CASA as supervised 180 (incorrectly shown as 114) 64 83 50 32 45 30 25 25 Nil 22 12 6 and no compass calibrations 15 runs 75 7 runs 99 Regulation 264 of the Civil Aviation Regulations 1988 (CAR) sets out the conditions under which the grant of a licence is to be refused: 264 Refusal to grant licence or certificate (1) CASA shall not refuse to grant a licence or certificate except on one or more of the following grounds, namely: (a) that the applicant has failed to satisfy a requirement prescribed by or specified under these regulations in relation to the grant of the licence or certificate; (b) that the applicant has made in, or in connection with, the application a statement that was false or misleading in a material particular; or ... (c) in relation to the initial issue of a licence or certificate: ... (i) that the applicant is not a fit and proper person to have the responsibilities and exercise and perform the functions and duties of a holder of the licence or certificate for which the application was made. 97. The respondent concedes that the applicant has satisfied the three categories of engine installation, fuel metering and control (carburettor) and mechanical maintenance. In addition, for the reasons given above, I find that he has also satisfied the requirements for scheduled maintenance. As regards the other six categories, there is insufficient evidence to warrant a finding that the applicant has accumulated the levels of experience required. 98. As was indicated above, a case can be made for the view that Mr Ekinci ’s own certification in relation to relevant electrical and instrument performed on the MiG-15s should be accepted. The respondent contends that the SoE is a statutory instrument that requires independent verification of all entries. CASA also argues that allowing an applicant to verify his or her own entries in an SoE is inherently problematic and, if accepted, would undermine the entire air safety purpose of the statutory licensing regime. It is undoubtedly true that a general system of self-supervision of aircraft maintenance would have potentially disastrous air safety consequences. It is less clear that accepting self-verification for a relatively small number of hours performed on historical or ex-military aircraft by an LIS-2 maintenance authority holder such as the applicant would be equally imprudent. I do not read CAO 100.92.5.3, taken in conjunction with paragraphs 3.5, 5.1 and 5.2 1/07/2014 12:22 PM Ekinci and Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2005] AATA 789 (18 Augus... http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/cth/AATA/2005/789... 20 of 20 of the SoE, as totally excluding the possibility of accepting some tasks certified in that way. Mr Edwards’ evidence indicated that, in certain circumstances, unorthodox methods of certification can be accepted. As allowing the relevant MiG hours in this case would make no difference to the outcome of the application, however, it is not necessary to resolve that issue. 99. I also find that there is insufficient evidence before the tribunal to establish the applicant has demonstrated four years of general aircraft maintenance experience, including two years aircraft maintenance experience in group 1 engines. 100. As to the other grounds advanced by the respondent for refusing to grant a licence to the applicant, I find that the applicant made in, or in connection with, the application a statement that was false or misleading in a material particular within the meaning of CAR 264(1)(b). On the other hand, I do not think the evidence supports a finding that the applicant is not a fit and proper person to hold a licence of the relevant type. 101. The applicant has thus not satisfied the requirements for the grant of an aircraft maintenance engineer’s licence and the decision under review must be affirmed. I certify that the 101 preceding paragraphs are a true copy of the reasons for the decision herein of Professor GD Walker, Deputy President Signed: ..................................................................................... Associate Date/s of Hearing 13 April, 20 June, 21 June, 22 June and 18 July 2005 Date of Decision 18 August 2005 Solicitor for the Applicant Unrepresented applicant Counsel for the Respondent Mr F Assaf Solicitor for the Respondent Mr A Anastasi CASA AustLII: Copyright Policy | Disclaimers | Privacy Policy | Feedback URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/cases/cth/AATA/2005/789.html 1/07/2014 12:22 PM