differentiated instructional strategies

advertisement

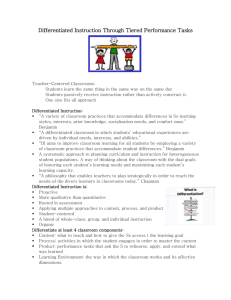

DIFFERENTIATED INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGIES G/T Curriculum Framework, Revised June 1, 2011 1 Differentiated Instructional Strategies In her book, The Differentiated Classroom: Responding to the Needs of All Learners, Tomlinson (1999) concurs with the National/State Leadership Training Institute on the Gifted and Talented that differentiation includes adaptations in content, process, product, affect, and, she adds, learning environment, in response to students’ readiness level, interests, and learning profile to ensure appropriate challenge and support for the full range of learners in a classroom (11). The teacher becomes a facilitator, assessor of students and planner of activities rather than an instructor. Tomlinson further reiterates that teachers may adapt one or more of the curricular elements (content, process, and products) based on one or more of the student characteristics (readiness, interest, learning profile) at any point in a lesson or unit (11). Differentiation engages students more deeply in their learning, provides for constant growth and development, and provides for a stimulating and exciting classroom. Differentiated instruction is intended to implement varied and continual assessment to guide instructional decisions and focus students’ learning goals. Teachers must be reminded that a differentiated classroom is less structured, busier and often less quiet than traditional teaching methods. The following strategies and descriptions can help teachers create differentiated classrooms. The strategies are organized by difficulty of implementation. Many of these strategies are adapted from Bertie Kingore’s Reading Strategies for Advanced Primary Readers and Differentiation: Simplified, Realistic, and Effective – How to Challenge Advanced Potentials in Mixed‐Ability Classrooms (2002, 2008). Some strategies can also be found on the Texas Performance Standards Project website, www.texaspsp.org, Instructional Strategies section. Simple to Implement Higher level questioning, anchoring activities, and flexible grouping are considered simple for the teacher to implement in the classroom. Higher Level Questioning During large group discussion activities, teachers can direct the higher level questions to the students who can handle them and adjust questions accordingly for students with greater needs. All students are answering important questions that require them to think, but the questions are targeted toward the student’s ability or readiness level. An easy tool for accomplishing this is to place cues on the classroom walls with key words that identify the varying levels of thinking, based on the revised Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, i.e., remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating. These verbs can also serve as cues for teachers when they are conducting class discussions and are useful for students when they are required to develop their own research questions (see chart at the end of this section). Bloom’s Taxonomy describes six levels of thinking. The levels are arranged sequentially from least to most complex. Teachers should use the higher levels of questioning to embed critical thinking skills into their lessons and assignments. Students may be referred to the different cues to assist them, depending on ability, readiness, or assignment requirements. With written quizzes the teacher may assign specific questions for each group of students. They all answer the same number of questions but the complexity required varies from group to group. The option to go beyond minimal requirements can be available for students who demonstrate that they require an additional challenge for their level. Additional information on higher level questioning can be found in the Thinking Skills section of the HISD G/T Curriculum Framework. Anchoring Activities Teachers may develop a list of activities that a student can do to at any time when they have completed present assignments or that can be assigned for a short period at the beginning of each class as students organize themselves and prepare for work. These activities may relate to specific needs or to enrichment opportunities, such as problems to solve or journals to write. They could also be part of a long‐term project that a student is working on. These activities may provide the teacher with time to provide specific help and small group instruction to students requiring additional help to get started or to students who may be working on G/T Curriculum Framework, Revised June 1, 2011 2 independent study projects. Students can work at different paces but always have productive work they can do. Teachers must be cautious that these activities are worthy of a student’s time and appropriate to their learning needs. Flexible Grouping According to the TPSP website, grouping within the classroom provides an optimal learning environment for all students. Flexible grouping is the practice of short‐term grouping and regrouping of students in response to the instructional objectives and students' needs. Kingore (2008) notes that flexible grouping recognizes that no single group placement matches all of a child's needs. With flexible grouping, students are assigned to groups in varied ways and for varied purposes. Groupings are flexible, varied working arrangements. They may be grouped for socialization or for production tasks. In a differentiated classroom that uses flexible grouping practices, whole‐class instruction can also be used for sharing introductory information and group‐ building experiences. Grouping can take place within a classroom, among grade‐level classrooms, across grade levels, throughout an entire school, or even between schools. Students can be grouped by skill, readiness, ability, interest, or learning style. Students’ readiness varies depending on personal talents and interests. Flexible grouping allows students to be appropriately challenged and avoids labeling a student’s readiness as static. Students should not be kept in a static group for any particular subjects as their learning will probably accelerate from time to time. Even highly talented students can benefit from flexible grouping. Often they benefit from work with intellectual peers, while occasionally in another group they can experience being a leader. Pettig (2000) notes that without flexible grouping practices, students’ needs for appropriate pace, level, and curriculum compacting are not addressed. Middle Range of Implementation Work stations, independent study projects, student experts, and production crew require a level of complexity for the teacher to implement in the classroom. Work Stations Teachers should use work stations that contain both differentiated and compulsory activities. A work station is not necessarily differentiated unless the activities are varied by complexity taking into account different levels of student ability, readiness, and interests. The work station should have clearly stated directions about its use and clearly stated student objectives, curricular purposes, and student expectations. It is important that students understand what is expected of them at the work station and are encouraged to manage their use of time. Work stations do not have to be elaborate, but should have interesting and inviting displays. They can be located on bookshelves or small tables. The activities, resources, and materials should be of varying levels and appeal to various learning styles. Instructions about how to choose tasks, where to go for help, how to store work, and a description of the rubrics and/or other evaluation criteria should be included. The degree of structure that is provided will vary according to the student’s independent work habits. At the end of each week students should be able to account for their use of time. Independent Study Projects The Texas Performance Standards Project (www.texaspsp.org) defines a project as consisting of the long‐term development of a question or idea that is significant or of personal interest to the student. Using interest surveys or student interest inventories (see section on Building Student Interest Inventories), teachers can help students identify topics of personal interest to them. Topics may or may not be related to the grade‐level or course content. The project allows students to develop an important content area question or idea in depth. Additionally, the project will demonstrate the use of sophisticated and advanced research methods and the use of technology appropriate to their topic of interest or the field of study. The project results in learning that is demonstrated through products or performances appropriate and comparable in quality to those of a professional who works in that field of study. For students, the project would encompass one aspect of the professionals’ work, e.g., demonstrate the investigative process utilized by an archaeologist, scientist, or G/T Curriculum Framework, Revised June 1, 2011 3 criminologist. A project generally consists of an abstract, a process record, a product, and a presentation and question‐and‐answer session. The product is the focus of the scoring process, and the selection of the format of the product must convey the knowledge and skills learned in the project. This culmination of the student’s comprehensive study must exhibit mastery of content and process skills. Each student project also includes a public presentation that consists of a brief explanation of the project and a question‐and‐answer session with the audience. The independent study project provides a research project where students learn how to develop the skills for independent learning. The degree of help and structure will vary between students and depend on their ability to manage ideas, time and productivity. An independent project differs from a work project in various ways: • Student‐defined topic • Student interest‐based • Student‐directed • Student‐controlled parameters • Investigations of real problems • Product development that is authentic • Emphasis on thinking skills, research skills, and learning‐to‐learn skills • More personal and requires more open‐endedness than teacher‐directed research projects In addition, Independent Study Projects • Require a personal interpretation and response • Develop from student interests and responds to the unanswered questions typical of gifted learners • Have no prescribed product –the product is an authentic extension of the research • Should begin in the early grades and never stop because the projects are driven by curiosity • Build upon research and independent working skills acquired through teacher‐guided studies The TPSP website, www.texaspsp.org, devotes a resource section for students to find information which they will need to pursue a project including the following, i.e., defining a project, choosing a topic, writing a proposal, choosing a mentor, and documenting product development. Student Experts An additional strategy found at TPSP website is the use of student experts. Many students have expertise in one area or a combination of areas. Some students are content experts and some are process experts, while others may be experts at utilizing tools, e.g., technological equipment. The teacher's time can be increased significantly if these areas of student expertise are discovered early in the year, nurtured, and used wisely. However, teachers should use caution when using student experts as a strategy. Students must have the option to volunteer for this work rather than being assigned this work. Gifted students are often used to do the teacher's work, and they feel their need to learn new knowledge and skills is being ignored. Procedures for establishing student experts 1. Have students sign up for one or more areas of expertise 2. Assess their level of expertise 3. License/accredit the student for the area(s) of expertise 4. Have student experts develop an appointment book for times they can be available 5. Have student experts keep a log of training they provide Areas of expertise • Public speaking, communication, writing • Content/topic/skills • Independent study process G/T Curriculum Framework, Revised June 1, 2011 4 • • • • • Creative problem solving process Deductive reasoning Graphic representation Production techniques Tools such as o Computer application programs o Photography equipment o Science equipment o Copier o Overhead projector o Sound equipment o Computer equipment Production Crews Production crews can get a big job done. It is a strategy found in the TPSP website’s Instructional Strategies section. The use of production crews can be effective if a project has many and varied products as parts of the whole. Teachers should have students who have an interest and some level of skill for the chosen task volunteer for the crew. Division of production tasks is evident in the workforce and can be just as effective in the classroom. The key is that each student has a meaningful task to complete and that each will be assessed on that task as it is related to the larger job. For example, a student may have an original idea but may lack the skills to convey that idea in a variety of ways. Production crews could take the original idea and create meaningful ways to sell it or present it to an appropriate audience. Appropriate presentations would include: presenting a play, musical, etc.; volunteer service project; school‐wide parent event or presentation; peer presentation; or a community presentation to a senior citizen group or neighborhood association group. Intensive and Sophisticated Implementation Finally, tiered assignments, curriculum compacting, and the School‐wide Enrichment Model (SEM) are examples of differentiated instructional strategies that require a more intensive level of complexity for the teacher to implement in the classroom. Curriculum compacting is discussed in the HISD G/T Curriculum Framework section Compacting the Curriculum. Tiered Assignments Tiered assignments are developed based on the foundation of tiered instruction. Tiered instruction attempts to align the curriculum to the different readiness levels of students and to respond to learner differences (Kingore 107). Tiered assignments are a differentiated instructional strategy found on the TPSP website that requires a greater level of difficulty for the teacher to implement. However, tiered assignments provide classroom options for all students to work on the same unit or in the same content area yet still be challenged individually. These tiered activities are a series of related tasks of varying complexity. Tiered assignments incorporate appropriately challenging tasks that vary in the content level of information, the thinking processes required, and the complexity of products students must create. These assorted assignments provide for differentiation by modifying learning situations, providing level activities, motivating students, and promoting success. Tiered activities engage students beyond what they find easy or comfortable, providing genuine challenges that help them progress. All of these activities are related to essential understanding and key skills that students need to acquire. Teachers assign the activities as alternative ways of reaching the same goals while taking into account individual student needs. Procedures for Developing a Tiered Activity 1. Select the concept, skill, or generalization to be addressed. 2. Determine the students' readiness and/or interests. G/T Curriculum Framework, Revised June 1, 2011 5 3. Create an activity that challenges students, is interesting, and promotes understanding of key concepts. 4. Create additional activities that require high levels of thinking, are interesting, and use advanced resources and technology. Determine the complexity of each activity to challenge above‐grade‐ level students and gifted learners. 5. Ensure that each student is assigned a variation of the activity that corresponds to that student's readiness level. Tiered assignments provide different levels of learning tasks within the same unit or topic. The assignments are tiered by content, process, and product. The complexity of the activity is tiered into several layers of difficulty. Tiered assignments provide an opportunity to accelerate instruction for G/T students. Tiered Assignment Example (www.texaspsp.org) Prerequisites: The teacher has: 1. reviewed pertinent data on students' abilities, interests, learning styles, and production modalities. 2. pre‐assessed the students on the material to be learned. 3. compacted the curriculum according to the pre‐assessment data. 4. organized instruction using flexible grouping. 5. determined a clear understanding of the expected student performance as a result of the assignment. Learning objective: Students will use agreed‐upon criteria to justify information on the issue of global warming, examining a variety of primary and secondary sources. They will draw conclusions based on their findings and relate the information to the idea that conflict is a catalyst for change. Findings will be presented to the class through an oral presentation using a graphic organizer or a teacher‐approved product of choice. Introductory activity: The teacher asks the question, "What do we know about the issue of global warming?" Student answers are recorded. The teacher then asks, "As scientists, what criteria might we use to judge the validity of the information regarding global warming?" The criteria are posted for future reference. Students are then asked to develop a concept map representing what they know about the issue. Using the two pre‐ assessment techniques, the teacher determines that there are three distinct levels of readiness to accomplish the task. All students will use the posted criteria to judge the information they will use for the activity. Tier I: Students will use reading material that pictorially represents required information and conduct a pre‐ developed survey of science teachers and students to determine their awareness of the issue, beliefs about the issue, and reasons for those beliefs. Students will apply the validity criteria to the information gathered. Findings will be presented. Tier II: Students will use grade‐level reading material to gather secondary information and develop and conduct a survey of a least two scientists currently investigating the issue. Students will apply the validity criteria to the information gathered. Findings will be presented. Tier III: Students will compare their knowledge of global warming with at least one other environmental issue and note the similarities and differences in the evidence that is presented by each side of the issue. Other dimensions of depth and complexity can be used to have students identify the patterns in order to predict implications over time, identify factors or trends that led to global warming and other environmental issues, or question what is still unanswered and determine if any conclusions about environmental issues need further investigation. Findings will be presented to an appropriate audience. Culminating activity: Students present their findings on global warming and explain how this issue is an example of conflict as a catalyst for change. After all presentations are completed, the teacher asks, "What can we generally say about the issue of global warming? What predictions can we make based on our current knowledge of this issue? What value, if any, do the validity criteria have in drawing defensible conclusions?" G/T Curriculum Framework, Revised June 1, 2011 6 The complexity of tiered activities is determined by the specific needs of the learners in a class. The levels of the activities begin at the readiness levels of the students and continue to stretch the students slightly beyond their comfort zones to promote continual development. All tiers require teacher modeling and support. School‐wide Enrichment Model (SEM) The School‐wide Enrichment Model (SEM) is a detailed blueprint for total school improvement. The original Enrichment Triad Model (Renzulli, 1976) was developed in the mid‐1970s. This research‐based model is based on highly successful practices that originated in special programs for the gifted and talented students. Its major goal is to promote both challenging and enjoyable high‐end learning across a wide range of school types, levels and demographic differences. The idea is to create a range of services that can be integrated to create meaningful, high‐level and potentially creative opportunities for students to develop their talents. SEM suggests that teachers should examine ways to make classrooms more inviting, friendly, and enjoyable places that encourage the full development of the learner. This model has been successful in addressing the problem of students who have been under‐challenged. SEM encourages creative productivity on the part of students by exposing them to various topics, areas of interest, and fields of study, and to further train them to apply advanced content, process‐training skills, and methodology training to areas of interest. For that reason, three types of enrichment are included in the Triad Model (see end of section). Type I enrichment is designed to expose students to a wide variety of disciplines, topics, occupations, hobbies, persons, places, and events that would not ordinarily be covered in the regular curriculum. In schools that use this model, an enrichment team consisting of parents, teachers, and students often organizes and plans Type I experiences by contacting speakers, arranging mini‐courses, demonstrations, or performances, or by ordering and distributing films, DVDs, videotapes, or other print or non‐print media. Type II enrichment consists of materials and methods designed to promote the development of thinking and feeling processes. Some Type II training is general and is usually carried out both in classrooms and in enrichment programs or as an out‐of‐school option. Training activities include the development of (1) creative thinking; problem solving and critical thinking skills; and affective processes; (2) a wide variety of specific “learning how‐to‐learn” skills; (3) skills in the appropriate use of advanced‐level reference materials; and (4) written, oral, and visual communication skills. Other Type II enrichment is specific, cannot be planned in advance, and usually involves an interest area selected by the student. For example, a student who becomes interested in botany after a Type I experience might pursue additional training in this area by doing advanced reading in botany; compiling, planning and carrying out plant experiments; and seeking more advanced training if he or she wants to go further. Type III enrichment involves students who become interested in pursuing a self‐selected area of interest and are willing to commit the time necessary for acquiring advanced content and training. The goals of Type III enrichment include: • • • • providing opportunities for applying interests, knowledge, creative ideas and task commitment to a self‐selected problem or field of study; acquiring advanced level understanding of the content and process that are used within the particular discipline or field of study; developing authentic products that are primarily directed toward developing a solution or bringing about an impact to an unpredictable real‐world situation or unresolved issue and directed toward an authentic audience; developing self‐directed learning skills in the areas of planning, organizing, utilizing resources, managing time, making decisions, and self‐evaluation; Additional information on Type III advanced level products can be found in the Advanced Level Products section of the HISD G/T Curriculum Framework and . G/T Curriculum Framework, Revised June 1, 2011 7 Works Cited Kingore, Bertie, ed. Reading Strategies for Advanced Primary Readers. Austin, TX: Texas Reading Initiative Task Force for the Education of Primary Gifted Children, 2002. Print. ‐‐‐. Differentiation: Simplified, Realistic, and Effective – How to Challenge Advanced Potentials in Mixed‐Ability Classrooms. Austin: Professional Associates Publishing, 2008. Print. Pettig, Kim. “On the Road to Differentiated Practice.” Educational Leadership, 58 (2000): 14‐18. Print. Recommended Reading Tomlinson, Carol. The Differentiated Classroom: Responding to the Needs of All Learners. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 1999. Print. Tomlinson, Carol and Jay McTighe. Integrating: Differentiated Instruction Plus Understanding by Design. Alexandria, VA: ASCD, 2006. Print. Tomlinson, Carol, Catherine Brighton, Holly Hertberg, Carolyn Callahan, Tonya Moon, Kay Brimijoin, et al. “Differentiating Instruction in Response to Student Readiness, Interest, and Learning Profile in Academically Diverse Classrooms: A Review of the Literature.” Journal for the Education of the Gifted 27 (2003): 119‐145. Print. Winebrenner, Susan. Teaching Gifted Kids in the Regular Classroom. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit Publishing, Inc., 2001. Print. Recommended Resources for Differentiation with G/T Students Barton, Linda G. Quick Flip Questions for Critical Thinking. Wisconsin: Edupress, 1994. Print. “EduPress Products.” GHC Specialty Brands, LLC, 2011. Web. <http://www.highsmith.com/edupress/> “Depth and Complexity Icon Stamps—Small.” California: J Taylor Education, n.d. “J. Taylor Education Products.” JTaylor Education. Web. <http://www.jtayloreducation.com/> Johnsen, Susan K. and Kathryn L. Johnson. Independent Study Complete Kit‐2nd ed. Texas: Prufrock Press Inc., 2007. Print. Kaplan, Sandra and Bette Gould. Frames: Differentiating the Core Curriculum. California: J Taylor Education, n.d. Print. Prufrock Press Inc.: The Resource for Gifted, Advanced, and Special Needs Learners. Prufrock Press, Inc., 2006. Web. <http://www.prufrock.com/> “Renzulli Learning System.” Renzulli Learning Systems, LLC, 2011. Web. <www.renzullilearning.com> Texas Performance Standards Project. Texas Education Agency, 2006. Web. <www.texaspsp.org > “Texas Teacher G/T Toolkit II.” Texas Performance Standards Project. Texas Education Agency, 2006. Web. <www.texaspsp.org > G/T Curriculum Framework, Revised June 1, 2011 8 “THiNK with Depth and Complexity Icon Magnets.” California: J Taylor Education, n.d. Tredick, Kim. Differentiation Smart Reference Guide: Sharp Suggestions for a Differentiated Classroom. California: J Taylor Education, n.d. Print. VanTassel‐Baska, Joyce and Tamra Stambaugh. Jacob’s Ladder Reading Comprehension Program. Texas: Prufrock Press Inc., 2008. Print. Voss, Marcy. Q3 Cards‐Quick, Quality, Question Cards for Differentiating Content with Dimensions of Depth and Complexity California: J Taylor Education, 2009. Print. Westphal, Laurie. Differentiating Instruction with Menus (Science, Social Studies, Language Arts, Math). Texas: Prufrock Press Inc., 2007. Print. Wilkes, Paula and Mark Szymanski. Deep and Complex Look Books: Differentiating Learning for All Students Through the Icons of Depth and Complexity. California: J Taylor Education, 2009. Print. G/T Curriculum Framework, Revised June 1, 2011 9 G/T Curriculum Framework, Revised June 1, 2011 10 Renzulli,, J.S. & Reis, S. M. The Schoolwide Enrichment Model: A How-to Guide for Educational Excellence, Creative Learning Press, Inc., 1997. Renzulli’s School‐wide Enrichment Model Type II enrichment consists of materials and methods designed to promote the development of thinking and feeling processes. Some Type II training is general and is usually carried out both in classrooms and in enrichment programs or as an out-ofschool option. Training activities include the development of (1) creative thinking; problem solving and critical thinking skills; and affective processes; (2) a wide variety of specific “learning how-to-learn” skills; (3) skills in the appropriate use of advanced-level reference materials; and (4) written, oral, and visual communication skills. Other Type II enrichment is specific, cannot be planned in advance, and usually involves an interest area selected by the student. For example, a student who becomes interested in botany after a Type I experience might pursue additional training in this area by doing advanced reading in botany; compiling, planning and carrying out plant experiments; and seeking more advanced training if he or she wants to go further. Type I enrichment is designed to expose students to a wide variety of disciplines, topics, occupations, hobbies, persons, places, and events that would not ordinarily be covered in the regular curriculum. In schools that use this model, an enrichment team consisting of parents, teachers, and students often organizes and plans Type I speakers, experiences by contacting arranging mini-courses, demonstrations, or performances, or by ordering and distributing films, DVDs, videotapes, or other print or non-print media. The highest level of enrichment that will produce advanced level products is Type III enrichment, with activities which involve students who become interested in pursuing a selfselected area of interest and are willing to commit the time necessary for acquiring advanced content and process training and in which they assume the role of a first-hand inquirer. The one overriding goal of Type III enrichment is that students begin to think, feel, and act like creative producers. Potentially able young artists and scholars develop the attitude that has reinforced the essence of creative individuals: I can do...I can be...I can create. G/T Curriculum Framework, Revised June 1, 2011 11 Bloom's Taxonomy In 1956, Benjamin Bloom headed a group of educational psychologists who developed a classification of levels of intellectual behavior important in learning. During the 1990's a new group of cognitive psychologists, lead by Lorin Anderson (a former student of Bloom's), updated the taxonomy reflecting relevance to 21st century work. The graphic is a representation of the NEW verbiage associated with the long familiar Bloom's Taxonomy. Note the change from nouns to verbs to describe the different levels of the taxonomy. New Version Old Version New Version verbiage: Remembering: can the student recall or remember the information? define, duplicate, list, memorize, recall, repeat, reproduce state Understanding: can the student explain ideas or concepts? classify, describe, discuss, explain, identify, locate, recognize, report, select, translate, paraphrase Applying: can the student use the information in a new way? choose, demonstrate, dramatize, employ, illustrate, interpret, operate, schedule, sketch, solve, use, write. Analyzing: can the student distinguish between the different parts? appraise, compare, contrast, criticize, differentiate, discriminate, distinguish, examine, experiment, question, test. Evaluating: can the student justify a stand appraise, argue, defend, judge, select, support, value, evaluate or decision? Creating: can the student create new product or point of view? assemble, construct, create, design, develop, formulate, write. Richard C. Overbaugh Lynn Schultz Old Dominion University G/T Curriculum Framework, Revised June 1, 2011 12 G/T Curriculum Framework, Revised June 1, 2011 13