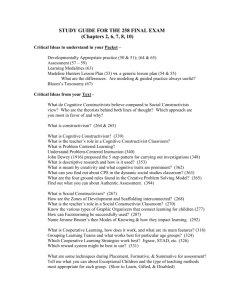

a constructivist approach to online training for online teachers

advertisement