ANS Plan - Adirondack Watershed Institute

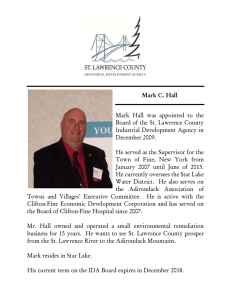

advertisement