PCT International Search and Preliminary Examination

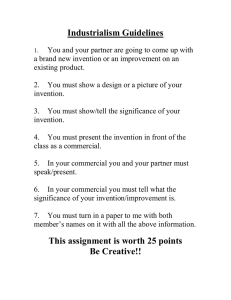

advertisement