Rural Homelessness Study

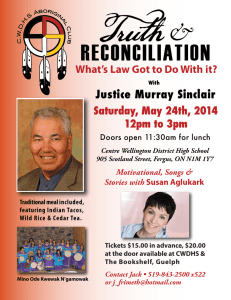

advertisement