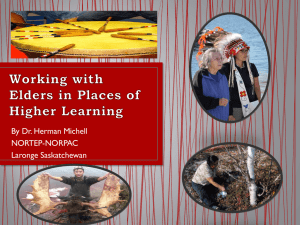

Elder Protocol and Guidelines - Provost

advertisement