Admissions and Placement Policies in Two Illinois Universities

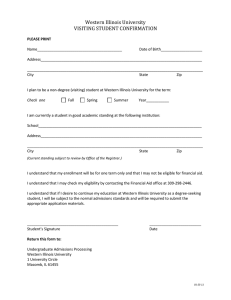

advertisement