Laser Diode and LED fundamentals

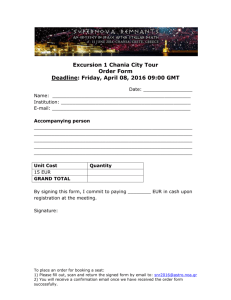

advertisement

LED Fundamentals Prof. Yiannis Kaliakatsos Dept of Electronics, T.E.I. of Crete giankal@chania.teicrete.gr LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 In this lecture we will review the mechanisms of light generation from semiconductor materials and we will focus on Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs) The aim of the lecture is to give you some fundamental concepts of light generation from inorganic semiconductor materials in order to have a comparison between them and similar devices from organic semiconductor materials LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 INTRODUCTION Photonic semiconductor devices are those in which the photon plays a major role They are divided into three groups: • Devices as light sources (LED, Laser Diode) • Devices as light detectors (Photodiode) • Devices as light converters (Solar Cell) In this lecture we will examine devices of the first group LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 LED and Laser Diode belong to the luminescent device group. Luminescence is the emission of optical radiation as a result of electronic radiation in a device or material, excluding any radiation that is purely the result of the temperature of the material (incandescence). A semiconductor emits electromagnetic radiation (in form of light), commonly, when excess electrons that have been injected into the conduction band of a semiconductor fall into the valence band releasing the energy difference as photons Next figure demonstrates schematically the basic recombination transitions of excess carriers in a semiconductor Not all transitions occur in the same material or under the same conditions and not all the transitions are radiative LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 EC ED Et Eg EA EV Band-to-band recombination Recombination through impurities or defects LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Auger transition LIGHT EMISSION FROM SEMICONDUCTORS The following phenomena related with light emission are the important for our discussion • Absorption • Spontaneous Emission • Stimulated Emission These are shown schematically in the next slide LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 most Figure 1. Radiative recombination processes: a) absorption, b) spontaneous emission, c) stimulated emission. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Spontaneous emission When an electron in an excited state in the conduction band falls back into the valence band releases its excess energy in the form of a photon with an energy given by: The photon emitted by the electron during this process has a random phase and direction. The rate at which excited electrons will spontaneously emit photons is given by, 𝑅𝑠𝑝0 = 𝐵𝑟 𝑛0 𝑝0 Where Br is the transition probability of an excited particle falling into a vacant lower state. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 In equilibrium, the rate at which electrons are excited into the conduction band is equal to the rate of electrons falling back to the valence band. If the concentration of electron-hole pairs increase 𝑛 = ∆𝑛 + 𝑛0 , 𝑝 = ∆𝑝 + 𝑝0 The recombination rate also increase 𝑅𝑠𝑝 = 𝐵𝑟 ∆𝑛 + 𝑛0 )( ∆𝑝 + 𝑝0 = 𝐵𝑟 𝑝0 𝑛0 + 𝑛0 △ 𝑝 + 𝑝0 △ 𝑛 +△ 𝑛 △ 𝑝 = 𝑅𝑠𝑝0 + 𝑅𝑠𝑝𝑒𝑥 where 𝑅𝑠𝑝𝑒𝑥 = 𝐵𝑟 𝑛0 △ 𝑝 + 𝑝0 △ 𝑛 +△ 𝑛 △ 𝑝 is the excess recombination rate producing the light LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 If we would like to have continuous light emission we need to keep this excess recombination rate LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Interband transitions, (Band-to-band) A semiconductor is always one of two types, a direct band gap or an indirect band gap. The minimal-energy state in the conduction band, and the maximal-energy state in the valence band, are each characterized by a certain k-vector. If the k-vectors are the same, it is called a "direct gap". If they are different, it is called an "indirect gap". You can see this schematically in the next figure LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Conduction Band Valence Band Energy Energy Valence Band Conduction Band Momentum Momentum Direct gap semiconductor Indirect gap semiconductor LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Either for photon absorption or emission the conventional theory for optical transitions between the valence and the conduction bands of the semiconductor is based on the so-called k-selection rule, i.e. the transition must conserve the total wave vector of the system (conservation of energy and crystal momentum) If the electron is near the bottom of the conduction band and the hole is near the top of the valence band (as is usually the case), this process is possible in a direct band gap semiconductor, but impossible in an indirect band gap one, because conservation of crystal momentum would be violated. For radiative recombination to occur in an indirect band gap material, the process must also involve the absorption or emission of a phonon, where the phonon momentum equals the difference between the electron and hole momentum. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 The involvement of the phonon makes this process much less likely to occur in a given span of time, which is why radiative recombination is far slower in indirect band gap materials than direct band gap ones. This is why light-emitting and laser diodes are almost always made of direct band gap materials, and not indirect band gap ones If for other reasons, i.e. color emission, we use indirect band gap semiconductors, we need to be 'altered„ them in order to enhance their radiative processes. T This is usually accomplished by introducing specific impurities (such as nitrogen) into the indirect band-gap semiconductor to form efficient radiative recombination centers within them. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Band-to-band recombination depends on the density of available electrons and holes. Both carrier types need to be available in the recombination process. Therefore, the rate is expected to be proportional to the product of n and p. Also, in thermal equilibrium, the recombination rate must equal the generation rate since there is no net recombination or generation. As the product of n and p equals ni2 in thermal equilibrium, the net recombination rate can be expressed as: 𝑅21 = 𝐵21 (𝑛𝑝 − 𝑛𝑖2 ) where B21 is the bimolecular recombination constant. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Trap assisted recombination The net recombination rate for trap-assisted recombination is given by 𝑅𝑡 = 𝑝𝑛 − 𝑛𝑖2 𝐸 − 𝐸𝑡 𝑝 + 𝑛 + 2𝑛𝑖 𝑐𝑜𝑠ℎ 𝑖 𝑘𝑇 𝑁𝑡 𝜐𝑡ℎ 𝜎 The derivation of this equation is beyond the scope of this text This expression can be further simplified for n >> p to: 𝑝𝑛 − 𝑝𝑛0 1 𝑈𝑝 = 𝑅𝑝 − 𝐺𝑝 = 𝑤ℎ𝑒𝑟𝑒 𝜏𝑝 = 𝜏𝑛 = 𝜏𝑝 𝑁𝑡 𝜐𝑡ℎ 𝜎 LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Excitation mechanism for LEDs and Diode Lasers Both LEDs (Light Emitting Diodes) and Diode Lasers are in principle p-n semiconductor diodes. Injection electroluminescence is the most important method of excitation in p-n junction. In this type of devices when a forward bias is applied to the p-n junction the injection of minority carriers across the junction can give rise to efficient radiative recombination since electric energy can be converted directly into photons. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 The aforementioned are shown schematically in the following figures p p n+ eV0 n+ EV EV Eg EF Eg hν hν=Eg hν hν eV0 EC EC V + p-n junction without bias - forward bias p-n junction LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 The previous figure shows the energy band diagram of an unbiased pn+ junction device in which the n-side is more heavily doped than the p-side. The band energy diagram is drawn to keep the Fermi level uniform through the device which is a requirement of equilibrium with no applied bias. The depletion region in a pn+ device extends mainly on the p-side. There is a potential energy barrier eVo , where Vo is the built-in potential. The higher concentration of free electrons in the n-side encourages the diffusion of conduction electrons from the n to the pside. This net electron diffusion is prevented by the electron barrier eVo. As soon as a forward bias V is applied, this voltage drops across the depletion region since this is the most resistive part of the device. As a result the built-in potential is reduced to Vo - V which allows the electrons from the n+ side to diffuse, or become injected into the pside, as in figure b LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 In equilibrium the minority carriers in p and n regions are given by np0 and pn0 respectively (in our case with p-n+ semiconductor pn0 ≈ 0) and with a forward bias we have an excess of minority carriers in the p region given by: ∆𝑛𝑝 = 𝑛𝑝 − 𝑛𝑝0 = 𝑞𝑉 𝑛𝑝0 (𝑒 𝑘𝑇 − 1); ∆𝑝 ≈ 0 and thus: 𝑅𝑠𝑝𝑒𝑥 = 𝐵𝑟 𝑛0 △ 𝑝 + 𝑝0 △ 𝑛 +△ 𝑛 △ 𝑝 ≈ 𝐵𝑟 𝑝0 △ 𝑛 = = 𝑞𝑉 𝑅𝑠𝑝 𝑒 𝑘𝑇 −1 LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 𝑞𝑉 𝐵𝑟 𝑝0 𝑛𝑝0 𝑒 𝑘𝑇 −1 As the forward current through the p-n junction is: 𝐼= 𝑞𝑉 𝐼𝑠 𝑒 𝑘𝑇 −1 Hence the recombination rate increases linearly with the forward current: 𝑅𝑠𝑝𝑒𝑥 ~𝐼 As shown in the figure LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 LED STRUCTURE There are various types of LED structure. It depends on the application what is the favor structure. In any case we attempt to have the highest luminous efficiency. We prefer the most of radiative recombination to take place from the side of the junction nearest the surface, since then the chances of re-absorption are lessened. Such a structure is shown in the next figure and it is known as planar LED LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 This is the simplest LED structure. It is fabricated by epitaxially growing doped semiconductor layers on a suitable substrate (e.g. GaAs or GaP) as depicted in the following figure. The substrate is an essential mechanical support and can be of different material a LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 b The p-side is on the surface from which the light is emitted and is therefore made narrow (a few microns) to allow the photons to escape without being reabsorbed. The photons that are emitted towards the n-side become either absorbed or reflected back at the substrate interface depending on the substrate thickness and the exact structure of the LED. The use of a segment electrode will encourage reflections from the semiconductor-air interface. (fig a) It is also possible to form the p-side by diffusing dopants into the epitaxial n+ - layer which is a diffuse junction planar LED as illustrated in figure b. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Not all light rays reaching the semiconductor –air interface can escape due to the total internal reflection. Those rays with angles of incidence grater than the critical value θC become reflected as shown in the next figure LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Light output p n+ Total reflection reabsorbed substrate To reduce the internal total reflection we construct LED with a special structure with the same of a dom for the p-side like in the next figure a. As this type of construction is rather expensive and the p-side is extended to the air we prefer to encapsulate the p-side with a plastic transparent material like in figure b LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Burrus LEDs or Surface Emitter LEDs It was design to be suitable to fiber optics communication LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 The edge emitting LED The edge emitting LED use an active area having stripe geometry. Because the layers above and below the stripe have different refractive indices acting as a waveguide for the emitted light. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 An heterostructure (heterojunction) diode is formatting when we have two different semiconductors in contact of different type anisotype heterojunction) or of the same type but with different concentrations (isotype heterojunction). The band diagram of an heterojunction compose a waveguide and this is very useful for LED construction as the light emitted in the limited area of this “wave guide” p-type p-type EC2 n-type EC2 n-type ΔEc ΔEc EC1 EC1 EF EF1 Eg2 Eg1 Eg2 Eg1 ΔEV EV1 EF2 ΔEV EV1 EV2 LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 WD EV2 Stripe geometry DH edge emitter LED (ELED). LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Materials for LED construction The main requirements for a suitable LED material are: The semiconductor material must have an energy gap of appropriate width; The semiconductor may exist in both p and n types, preferably with low resistivity Efficient radiative pathways must be present. They must have energy gaps greater than 2 eV for visible radiation. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 To chose the appropriate material for LED we have also to remember: The semiconductor bandgap energy defines the energy of the emitted photons in a LED. To fabricate LEDs that can emit photons from the infrared to the ultraviolet parts of the e.m. spectrum, we need to user several different material systems. No single system can span this energy band, at present, although the III-V nitrides come close. The criterion of luminous efficacy limits display diodes to p-n junctions in single-crystalline, zinc blended-structured III-V semiconductors. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 There are various direct gap semiconductor materials that can be readily doped to make commercial p-n junction LEDs. An important class of commercial semiconductor materials which cover the visible spectrum is the III-V ternary alloys based on GaAs and GaP which are denoted as GaAs1-yPy. When y<0,45 the alloy is a direct band gap semiconductor and the radiative recombination process is direct as shown in the following scheme. The rate of recombination is proportional to the product of electron and hole concentrations. The emitted wavelengths range from about 630 nm(red) for y=0,45 to 870 nm for y =0. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 GaAs1-yPy with y>0,45 are indirect gap semiconductor. The recombination processes occur through recombination centers and involve the creation of phonons rather than photons and the radiative recombination is negligible. If we add isoelectronic impurities, such as nitrogen (N) into the semiconductor crystal we introduce localized energy levels (electron traps). In this case the recombination take place through these centers and the emitted photons have energies slightly different to Eg . LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 The recombination process depends on the concentration of such impurities and in general the efficiency of LEDs is lower. However Nitrogen doped indirect band gap GaAs1-yPy alloys are widely used in inexpensive green, yellow and orange LEDs. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Another semiconductor used for LED construction is GaN. This is a direct band gap semiconductor with Eg = 3.4 eV. (≈365 nm) That means an emission spectrum in the ultraviolet region. In order to construct LEDs emitting blue light we use the InGaN alloy which has a band gap of Eg = 2,7 eV (≈ 460 nm, i.e. blue color). As GaN is a defect rich material with typical dislocation densities exceeding 108 cm−2. Light emission from InGaN layers grown on such GaN buffers used in blue and green LEDs is expected to be low because of non-radiative recombination at such defects. In the indium-rich regions, with a lower band gap than the surrounding material, most electron-hole pairs recombine and by the lower potential energy of these clusters carriers are hindered to diffuse and recombine non-radiatively at crystal defects. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Recently considerable progress made towards more efficient blue LEDs using direct band gap semiconductors of the II-VI group (i.e. ZnSe). The main problem is the current technological difficulty in appropriate doping to construct efficient pn-junctions. Usually for LED fabrication we use ternary (3 elements) or quaternary (4 elements) alloys based on III-V elements like, GaAs1-yPy or Al1-xGaxAs or In1-xGaxAs1-yPy. The composition can be varied to adjust the band gap and hence the emitted radiation to cover wide rang od wavelengths. In the following table are shown the materials used for LED‟s construction LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Color Wavelength (nm) Voltage (V) Infrared λ > 760 ΔV < 1.9 Red 610 < λ < 760 Semiconductor Material Gallium arsenide (GaAs) Aluminium gallium arsenide (AlGaAs) 1.63 < ΔV < 2.03 Aluminium gallium arsenide (AlGaAs) Gallium arsenide phosphide (GaAsP) Aluminium gallium indium phosphide (AlGaInP) Gallium(III) phosphide (GaP) Orange 590 < λ < 610 2.03 < ΔV < 2.10 Gallium arsenide phosphide (GaAsP) Aluminium gallium indium phosphide (AlGaInP) Gallium(III) phosphide (GaP) Yellow 570 < λ < 590 2.10 < ΔV < 2.18 Gallium arsenide phosphide (GaAsP) Aluminium gallium indium phosphide (AlGaInP) Gallium(III) phosphide (GaP) 1.9[36] < ΔV < 4.0 Indium gallium nitride (InGaN) / Gallium(III) nitride (GaN) Gallium(III) phosphide (GaP) Aluminium gallium indium phosphide (AlGaInP) Aluminium gallium phosphide (AlGaP) Green 500 < λ < 570 Blue 450 < λ < 500 2.48 < ΔV < 3.7 Zinc selenide (ZnSe) Indium gallium nitride (InGaN) Silicon carbide (SiC) as substrate Silicon (Si) as substrate — (under development) Violet 400 < λ < 450 2.76 < ΔV < 4.0 Indium gallium nitride (InGaN) Purple multiple types 2.48 < ΔV < 3.7 Dual blue/red LEDs, blue with red phosphor, or white with purple plastic Diamond (235 nm)[37] Boron nitride (215 nm)[38][39] Aluminium nitride (AlN) (210 nm)[40] Aluminium gallium nitride (AlGaN) Aluminium gallium indium nitride (AlGaInN) — (down to 210 nm Ultraviolet λ < 400 3.1 < ΔV < 4.4 White Broad spectrum ΔV = 3.5 Blue/UV diode with yellow phosphor LED Construction Efficient light emitter is also an efficient absorbers of radiation therefore, a shallow p-n junction required. Active materials (n and p) will be grown on a lattice matched substrate. The p-n junction will be forward biased with contacts made by metallisation to the upper and lower surfaces. Ought to leave the upper part „clear‟ so photon can escape. The silica provides passivation/device isolation and carrier confinement LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Efficient LED Need a p-n junction (preferably the same semiconductor material only different dopants) Recombination must occur Radiative transmission to give out the „right coloured LED‟ “Right coloured LED” hc/ = Ec-Ev = Eg so choose material with the right Eg Direct band gap semiconductors to allow efficient recombination All photons created must be able to leave the semiconductor Little or no reabsorption of photons LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Correct band gap Direct band gap Material Requirements Efficient radiative pathways must exist Material can be made p and n-type LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 LED spectrum Because the statistical nature of the recombination process between electrons and holes the emitted photons in spontaneous emission are in random directions. The spectrum of spontaneous emission has a threshold energy Eg, a peak at Eg+ ½ kT and a half power width of 1.8 kT. This translates into a spectrum width of The theoretical emission spectrum of a LED is given on the following figure LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 LED Spectrum characteristics Spectrum of a blue LED. Experimental emission spectra from various LEDs are shown in the aside figures. They can be described by the use of a Gaussian function. Therefore the spectral power density function can be given by: Spectrum of a red LED. 1 𝜆 − 𝜆𝑝𝑒𝑎𝑘 𝑃 𝜆 =𝑃 exp − 2 𝜎 𝜎 2𝜋 1 LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 2 Theoretical emission spectrum of a semiconductor exhibiting substantial alloy broadening. The full width at half maximum (FWHM) is related to the standard deviation by the equation shown in the figure LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 RGB System White light can be produced by mixing differently colored light, the most common method is to use red, green and blue (RGB). Combined spectra of a common blue LED, a yellow-green LED and a high brightness red LED. They took these spectra on an Ocean Optics HR2000 spectrometer This spectrum is not calibrated for intensity. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Temperature dependence of LED spectrum LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Temperature dependence of LED spectrum LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Light distribution from a LED This radiation diagram shows the output of a blue LED with a waterclear case (Photron PL-BA31). Most of the light is shooting straight out the front of the package. This radiation diagram shows the output of a green LED with a diffused colored case (Photron PLGB574G). LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Efficiency of a LED The internal quantum efficiency of a LED may approach unity but the total efficiencies are much lower due to reabsorption through the material and total reflections between the different materials (diodesubstrate, substrate – contacts, diode-air etc) LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) It gives a measure to how efficiently the device coverts electrons to photons and allows them to escape. It is the ratio of the number of photons emitted from the LED to the number of electrons passing through the device EQE = [Injection efficiency] x [Internal quantum efficiency] x [Extraction efficiency] LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-11 July 2011 Internal Quantum Efficiency (IQE) or Radiative Efficiency Not all electron-hole recombination are radiative. IQE is the proportion of all electron-hole recombination in the active region that are radiative, producing photons. Extraction Efficiency or Optical Efficiency Once the photons are produced within the semiconductor device, they have to escape from the crystal in order to produce a light-emitting effect. Extraction efficiency is the proportion of photons generated in the active region that escape from the device. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Wall-Plug Efficiency (also termed Radiant Efficiency) Wall-plug efficiency is the ratio of the radiant flux, measured in watts, and the electrical input power i.e the efficiency of converting electrical to optical power. Wall-Plug Efficiency = [EQE] x [Feeding efficiency] Feeding Efficiency Feeding efficiency is the ratio of the mean energy of the photons emitted and the total energy that an electron-hole pair acquires from the power source. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Efficiency’s calculation for various LEDs structure Injection Efficiency It is due to electron-hole recombination to produce photons. The electrons passing through the device have to be injected into the active region. Injection efficiency is the proportion of electrons passing through the device to those injected into the active region In the case of a planar LED this is given by LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Dome LEDs In a planar LED, due to the phenomenon of total reflection, the fraction F of the total generated radiation that is actually transmitted into the second medium is given by: A method to reduce the losses from total reflection, is to give to the LED a hemispherical or a parabolic scheme, like in the next figures LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Light Output versus Current Characteristic for a LED The light output power against current characteristics for a LED is given in the figure. LED is a very linear device and so it is suitable for analog optical transmission where severe constraints are put on the linearity of the optical source LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 I-V characteristic of a LED The I-V characteristic of a LED is similar to those of a forward bias p-n diode LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 ADVANTAGES OF LEDs Efficiency: LEDs produce more light per watt than incandescent bulbs. Their efficiency is not affected by shape and size, unlike fluorescent light bulbs or tubes. Color: LEDs can emit light of an intended color without the use of the color filters that traditional lighting methods require. This is more efficient and can lower initial costs. Size: LEDs can be very small (smaller than 2 mm2) and are easily populated onto printed circuit boards. On/Off time: LEDs light up very quickly. A typical red indicator LED will achieve full brightness in under a microsecond. LEDs used in communications devices can have even faster response times. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 ADVANTAGES OF LEDs Cycling: LEDs are ideal for use in applications that are subject to frequent on-off cycling, unlike fluorescent lamps that burn out more quickly when cycled frequently, or HID lamps that require a long time before restarting. Dimming: LEDs can very easily be dimmed either by pulse-width modulation or lowering the forward current. Cool light: In contrast to most light sources, LEDs radiate very little heat in the form of IR that can cause damage to sensitive objects or fabrics. Wasted energy is dispersed as heat through the base of the LED. Slow failure: LEDs mostly fail by dimming over time, rather than the abrupt burn-out of incandescent bulbs. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 ADVANTAGES OF LEDs Lifetime: LEDs can have a relatively long useful life. One report estimates 35,000 to 50,000 hours of useful life, though time to complete failure may be longer. Fluorescent tubes typically are rated at about 10,000 to 15,000 hours, depending partly on the conditions of use, and incandescent light bulbs at 1,000–2,000 hours. Shock resistance: LEDs, as solid state components, are difficult to damage with external shock, unlike fluorescent and incandescent bulbs which are fragile. Focus: The solid package of the LED can be designed to focus its light. Incandescent and fluorescent sources often require an external reflector to collect light and direct it in a usable manner. Toxicity: LEDs do not contain mercury, unlike fluorescent lamps. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 DISADVANTAGES OF LEDs Low Efficiency Fluorescent lamps are usually can be more efficient High initial price: LEDs are currently more expensive, price per lumen, on an initial capital cost basis, than most conventional lighting technologies. The additional expense partially stems from the relatively low lumen output and the drive circuitry and power supplies needed. Temperature dependence: LED performance largely depends on the ambient temperature of the operating environment. Over-driving the LED in high ambient temperatures may result in overheating of the LED package, eventually leading to device failure. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 DISADVANTAGES OF LEDs Voltage sensitivity: LEDs must be supplied with the voltage above the threshold and a current below the rating. This can involve series resistors or current-regulated power supplies. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 DISADVANTAGES OF LEDs Light quality: Most cool-white LEDs have spectra that differ significantly from a black body radiator like the sun or an incandescent light. The spike at 460 nm and dip at 500 nm can cause the color of objects to be perceived differently under cool-white LED illumination than sunlight or incandescent sources, due to metamerism, red surfaces being rendered particularly badly by typical phosphor based cool-white LEDs. However, the color rendering properties of common fluorescent lamps are often inferior to what is now available in state-of-art white LEDs. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 DISADVANTAGES OF LEDs Area light source: Incandescent Bulb radiation pattern LEDs do not approximate a “point source” of light, but rather a lambertian distribution. So LEDs are difficult to use in applications requiring a spherical light field. LEDs are not capable of providing divergence below a few degrees. LED Bulb radiation pattern This is contrasted with lasers, which can produce beams with divergences of 0.2 degrees or less. http://www.olino.org LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 DISADVANTAGES OF LEDs Blue pollution: Because cool-white LEDs emit proportionally more blue light than conventional outdoor light sources such as high-pressure sodium lamps, the strong wavelength dependence of Rayleigh scattering means that coolwhite LEDs can cause more light pollution than other light sources. The International Dark-Sky Association discourages the use of white light sources with correlated color temperature above 3,000 K LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 DISADVANTAGES OF LEDs Blue hazard: There is a concern that blue LEDs and cool-white LEDs are now capable of exceeding safe limits of the so-called blue-light hazard as defined in eye safety specifications such as ANSI/IESNA RP-27.1-05: Recommended Practice for Photobiological Safety for Lamp and Lamp Systems. Cool White LED, spectrum Warm White LED, spectrum LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 LED APPLICATIONS The applications of LEDs are very wide but they can categorized into four kinds: 1. In displays (Sign Applications) 2. In illumination 3. In telecommunication 4. In control systems LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Sign Applications With LEDs • • • • Full Color Video Monochrome Message Boards Traffic/VMS Transportation - Passenger Information Light Emitting Diodes in VMS (Variable Message Signs) have been widely used and accepted since the late 1980's. This "single color" signage is visible in a myriad of applications including traffic management, commercial advertising, shopping malls and public transportation to name a few. It wasn't until the mid 1990's with the advent and cost reduction of high brightness InGaN blue LEDs that full color, RGB LED signs began their major entry into the video display market. Sign builders often face a variety of difficulties when integrating RGB technology into their video systems LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Red lights in Taiwan will soon be much greener. By 2011, all traffic lights on the small island republic will be fitted with efficient LED lights thanks to a NT $229 million (US $7 million) project set to begin next year. Almost half of all traffic lights in Taiwan already use LEDs; the remaining 420,000 traffic lights will be converted over three years, providing an estimated savings of 85% in power consumption. http://www.inhabitat.com/2007/07/10/taiwans-led-traffic-lights/ LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Illumination With LEDs With the recent advent of White LEDs as well as advancements in ultra bright InGaAlP and GaN technologies, LEDs have begun to replace conventional type lighting in a variety of illumination applications. LEDs not only consume far less electricity than traditional forms of illumination, resulting in reduced energy costs, but require less maintenance and repair. Studies have shown that the use of LEDs in illumination applications can offer: Greater visual appeal Reduced energy costs Increased attention capture Savings in maintenance and lighting replacements LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Organic Light Emitting Diodes (OLED) Organic light emitting diodes (OLEDs) are optoelectronic devices based on small molecules or polymers that emit light when an electric current flows through them. Simple OLED consists of a fluorescent organic layer sandwiched between two metal electrodes. Under application of an electric field, electrons and holes are injected from the two electrodes into the organic layer, where they meet and recombine to produce light. They have been developed for applications in flat panel displays that provide visual imagery that is easy to read, vibrant in colors and less consuming of power. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Origin of band gap on an organic semiconductor LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 5-16 July 2010 OLED’s Advantages are light weight, durable, power efficient and ideal for portable applications. have fewer process steps and also use both fewer and low-cost materials than LCD displays. can replace the current technology in many applications due to following performance advantages over LCDs. Greater brightness Faster response time for full motion video Fuller viewing angles Lighter weight Greater environmental durability More power efficiency Broader operating temperature ranges Greater cost-effectiveness LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 OLED Dispay’s Advantages Self-luminousThe efficiency of OLEDs is better than that of other display technologies without the use of backlight, diffusers, and polarizers. Low cost and easy fabricationRoll-to-roll manufacturing process, such as, inkjet printing and screen printing, are possible for polymer OLEDs. Color selectivityThere are abundant organic materials to produce blue to red light. Lightweight, compact and thin devicesOLEDs are generally very thin, measuring only ~100 nm LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 OLED Dispay’s Advantages FlexibilityOLEDs can be easily fabricated on plastic substrates paving the way for flexible electronics. High brightness and high resolutionOLEDs are very bright at low operating voltage (White OLEDs can be as bright as 150,000 cd/m2) Wide viewing angle – OLED emission is lambertian and so the viewing angle is as high as 160 degrees Fast response – OLEDs EL decay time is < 1μs. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 OLED’s Disadvantages Highly susceptible to degradation by oxygen and water molecules. So the main disadvantage of an OLED is the lifetime. With proper encapsulation, lifetimes exceeding 60,000 hours have been demonstrated. Low glass transition temperature Tg for small molecular devices (>700 C). So the operating temperature cannot exceed the glass transition temperature. Low mobility due to amorphous nature of the organic molecules. LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011 Some OLED Applications TVs Cell Phone screens Computer Screens Keyboards (Optimus Maximus) Lights Portable Device displays LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4 -15 July 2011 Future OLED Applications OLEDs can be used in High-Resolution Holography (Volumetric Display). Professor Orbit showed on May 12, 2007, EXPO Lisbon the potential application of these materials to reproduce threedimensional video. OLEDs could also be used as solid-state light sources. OLED efficacies and lifetime already exceed those of incandescent light bulbs, and OLEDs are investigated worldwide as source for general illumination; LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4 -15 July 2011 References for further reading http://www.ecse.rpi.edu/~schubert/Light-Emitting-Diodes-dot-org/ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Light-emitting_diode http://www.materials.uoc.gr/el/undergrad/courses/ETY580/notes/optodevices.pdf http://www.phy.iitkgp.ernet.in/ptaccd2/Speakers_manuscript/ADhar.pdf (ORGANIC OPTOELECTRONICS : A FUTURE PROMISE) www.ece.rochester.edu/courses/ECE423/ECE223.../Lu_06.pdf http://www.madehow.com/Volume-1/Light-Emitting-Diode-LED.html http://www.springerlink.com/content/1302581718g54q38/ (Materials for light emitting diodes , R.J. Archer) www.riksutstallningar.se/upload/Semiarier/pdf/led.pdf (LED Characteristics. Erik Swennen & Patrick van der Meulen) www.pshk.org.hk/.../Green%20Automotive/.../20090508-08DrAlfredFELDEROSRAM_public.pdf (A Future Driver for Green. Applications in Lighting,. Automotive and Display. Dr. Alfred Felder ) http://www.solutionsforledlights.com/2008/08/applications-for-led-lighting.html LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4 -15 July 2011 Acknowledgments I would like to express my sincere thanks to: • • • • • E.U. LLP-ERASMUS IKY T.E.I. of Crete Thomas Anthopoulos from IC Costas Petridis and Popi Tsitou from T.E.I. • Our sponsors For their invaluable support LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4 -15 July 2011 Thank you for your attention We are waiting you to come back soon LLP-IP in Organic Electronics & Applications Chania Crete, 4-15 July 2011