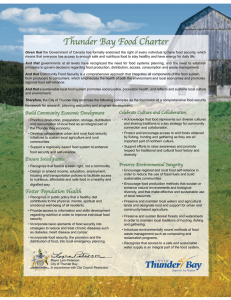

Poverty in Thunder Bay - Kinna

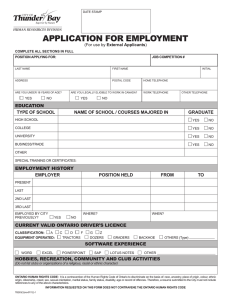

advertisement