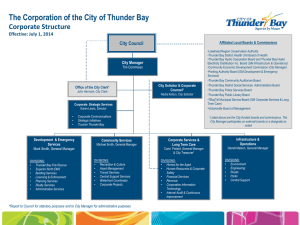

Under One Roof – Setting the Scene

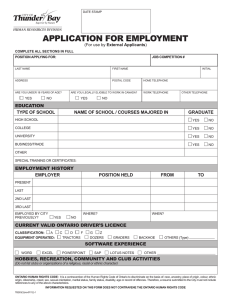

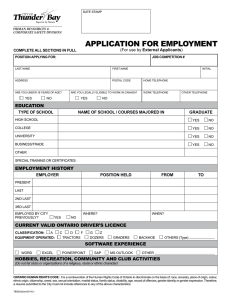

advertisement