Mar/Apr 2014

Your Resource for Ceramic Techniques

“In three

three years,

years, III have

have run

run 35

35 tons

tons of

of beautifully

“In

35

tons

of

beautifully

“In

three

years,

have

run

“In

threeclay

years,

I have

run

35 tonsmixer-pugmill.”

of beautifully

blended

clay

through

this

amazing

mixer-pugmill.”

blended

through

this

amazing

blended

blended clay

clay through

through this

this amazing

amazing mixer-pugmill.”

mixer-pugmill.”

PaulLatos,

Latos, Linn

Linn Pottery

Pottery

Paul

Paul Latos, Linn Pottery

using

the

Bailey

MSV25

Mixer-Pugmill

using

the Bailey

MSV25 Mixer-Pugmill

Paul Latos,

Linn MSV25

Pottery

using

the Bailey

Mixer-Pugmill

using

theare

Bailey

MSV25ofMixer-Pugmill

There

6 models

Bailey MSV Mixer/

There are 6 models of Bailey MSV Mixer/

There

are which

6which

models

Bailey

MSVany

Mixer/

Pugmills

pugoffaster

faster

than

any

other

Pugmills

pug

than

other

There

arewhich

6 models

of

Bailey

MSV

Pugmills

pug

faster

than

anyMixer/

other

mixer/pugmill

in

their

class.

mixer/pugmill

in

their

class.

Pugmills which

mixer/pugmill

in pug

theirfaster

class.than any other

Bailey “3

“3 Stage

Stage

Blending”

sets the

the standard

standard

mixer/pugmill

in Blending”

their

class.sets

Bailey

Bailey

“3 Stage

Blending”

sets the standard

forsuperior

superior

plastic

clay prepared

prepared

in the

the

for

plastic

clay

in

Bailey

“3time.

Stage

Blending”

sets theinstandard

for

superior

plastic

clay prepared

the

fastest

fastest

time.

for superior

fastest

time. plastic clay prepared in the

fastest time.

Bailey == Better

Better Blending!

Blending!

Bailey

Bailey

= Better Blending!

Bailey = Better Blending!

Bailey Builds

Builds the

the Best

Best Equipment!

Equipment!

Bailey

Equipment!

Bailey

Builds

Bailey

Builds the Best Equipment!

Get the lowest discount prices, best selection,

Get

selection,

Get the

the lowest

lowest discount

discount prices, best selection,

Get the lowest discount prices, best selection,

bestquality

qualityproducts,

products,and

and the

the best

best customer

customerservice.

service.

best

quality

products,

best

customer

service.

best quality products, and the best customer service.

Bailey 15”

15”Quick-Trim

Quick-Trim IIII

Bailey

Bailey

15”Quick-Trim

II

Bailey 15” Quick-Trim II

A fast low cost trimming tool with a 4 point hold.

fastlow

low

costtrimming

trimming

tool

with

point

hold.

Mounts

instantly

on anytool

wheel

with

bathold.

pins.

AA

fast

cost

with

aa4410”

point

Mounts

instantly

onany

anywheel

wheel

witha10”

10”

batpins.

pins.

A

fastbe

low

cost

trimming

tool counter-clockwise.

with

4 point

hold.

Can

used

clockwise

and

Mounts

instantly

on

with

bat

Can

be

used

clockwise

and

counter-clockwise.

Mounts

instantly

on

any

wheel

with

10”

bat

pins.

Holders

available

in 5 and

heights.

Great for Schools!

Can

be used

clockwise

counter-clockwise.

Holders

available

in 5 heights.

Great for Schools!

Can beavailable

used

clockwise

and counter-clockwise.

Holders

in 5 heights.

Great for Schools!

Holders available in 5 heights. Great for Schools!

World Famous

World Famous

Famous

World

Bailey Famous

Slab Rollers

World

Bailey

Slab Rollers

Rollers

Bailey

Slab

Free

Freight

Specials

Bailey

Slab Rollers

Free

Freight

Specials

Free Freight Specials

Free Freight Specials

Bailey Wheels

Bailey

Wheels

Bailey

Wheels

Shimpo

C.I. Brent

Bailey

Wheels

Shimpo

C.I.

Shimpo

C.I. Brent

Brent

...and

more!

Shimpo

C.I. Brent

...and

more!

...and

more!

...and more!

World Famous

World

Famous

World

Famous

BaileyFamous

Extruders

World

Bailey

Extruders

Bailey

Extruders

...go

with

the best!

Bailey

Extruders

...go

the

...gowith

with

thebest!

best!

...go with the best!

Grip

Grip

Grip

those

Grip

those

those

bats!

those

bats!

bats!

bats!

Bat-Gripper™

Nitride Bonded

Bonded

Nitride

Bat-Gripper™

Hold down

downloose

loose

High

Alumina

Shelves

Bat-Gripper™

Nitride

Bonded

Nitride

Bonded

Bat-Gripper™

High Alumina Shelves

Hold

anddown

worn

bats

Corelite

Shelves

loose

High

Alumina

Shelves

High

Alumina

Shelves Hold

Hold

downbats

loose

Corelite

Shelves

and

worn

and

Corelite

Shelves

Corelite

Shelves

andworn

wornbats

bats

Largestselection

selectionofoftools,

tools,stains,

stains,and

andglazes

glazesatat

Largest

Largest

selection

and glazes

glazes at

at

superdiscounts!

discounts!

Largest

selection of

of tools,

tools, stains,

stains, and

super

super

super discounts!

discounts!

www.BaileyPottery.com

www.BaileyPottery.com

www.BaileyPottery.com

www.BaileyPottery.com

Glaze&&Wedge

WedgeTables

Tables

Glaze

Dust

Solutions

Glaze

&

Wedge

Tables

Glaze

&

Wedge

Tables

Dust Solutions

RackSolutions

Systems

Dust

Solutions

Dust

Rack

Systems

RackSystems

Systems

Rack

TollFree:

Free:800-431-6067

800-431-6067oror845-339-3721

845-339-3721

Toll

Toll

800-431-6067

or

845-339-3721

Free:

800-431-6067

or

845-339-3721

Fax:

845-339-5530

Fax: 845-339-5530

Fax:

845-339-5530

845-339-5530

Email:

info@baileypottery.com

Email:

info@baileypottery.com

Email: info@baileypottery.com

info@baileypottery.com

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

1

Share

your story...

FireBox 8x6LT

• 8”x8”x6”Chamber

• Ramp/Hold

• ShelfKitIncluded

• PresetPrograms

• 2YearWarranty

Ceramics

• EasyStorage

Glass

MetalClay

...win this kiln

WearecompletelyoverhaulingourwebsiteandwewanttofeatureYOU!Afterall,whoknows

moreabouthowPottersuseourkilnsthanPotters.

Allentrieswillwinsomething,andoneluckyPotterwillbringhometheFireBox8x6LT.Goto

thelinkbeloworscantheQRcodefordetailsonhowtoenter.

http://skutt.com/potter/fun-stuff/contest

For more information on Skutt Kilns or to find a distributor, visit us at www.skutt.com or call us directly at 503.774.6000

2

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

Photo: Brian Giniewski

Inside

March/April 2014 Volume 17 Number 2

Features

12 Pattern and Meaning by Shana Salaff

Adding pattern to your work is a great way to personalize it and explore subjects that fascinate you.

17 Bryce Brisco: The Art of Serving

by Yoko Sekino-Bove

Making dinnerware requires attention to both the details

that make functional pieces work, and the ones that

make them a pleasure to use.

12

22

22 Push/Pull: The Art of Deborah Sigel

by Mary Cloonan

Working with Egyptian paste is no easy feat, but Deborah Sigel has found an elegant solution.

29 Oil Bottle and Trivet: Altering in Unison

by Marty Fielding

Handbuilding a bottle and tray using wheel-thrown parts

allows for lots of creative possibilities.

17

35 Making Pots (and Food) from Scratch

by Patty Osborne

On a visit to a potters’ cooperative in Nicaragua, members of Potters for Peace learned a new firing technique.

41 Used Once and Once Again by WangLing Chou

Tired of having all those plastic beverage bottles go to

waste? Try turning them into molds for functional vessels.

In the Studio

6 One Man’s Trash by Deanna Ranlett

8 Brick Façades by Robert Balaban

29

10 Building Big, Carving Deep by Barbara Stevens

Inspiration

44 In the Potter’s Kitchen

Egg Separators by Sumi von Dassow

48 Pottery Illustrated

Brushes by Robin Ouellette

41

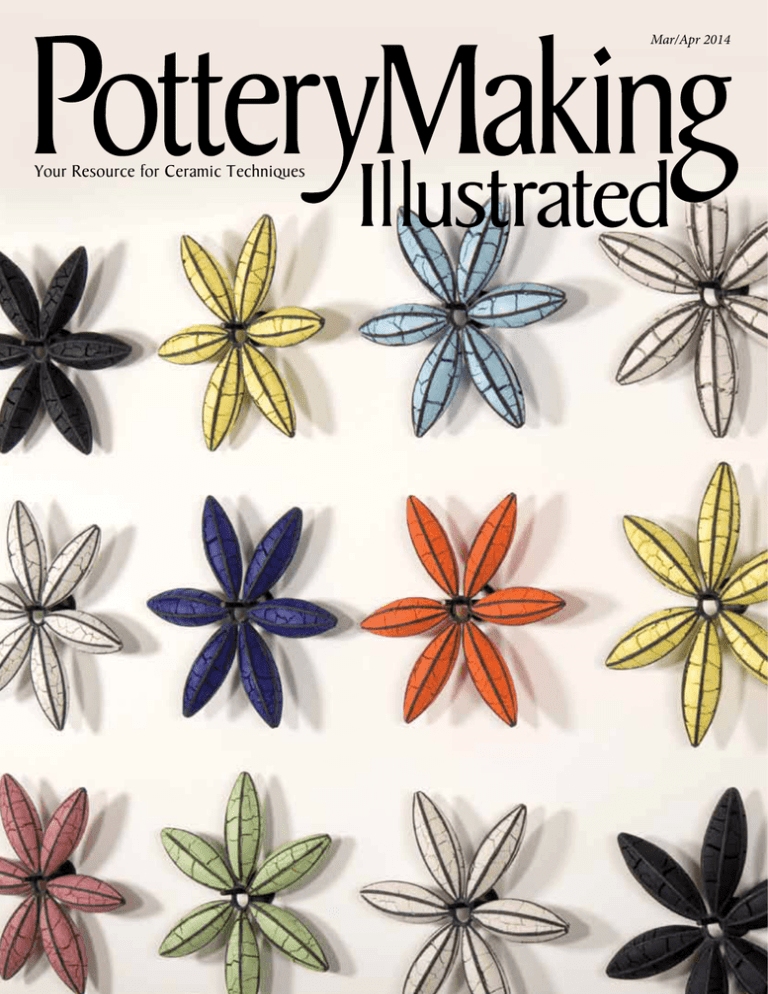

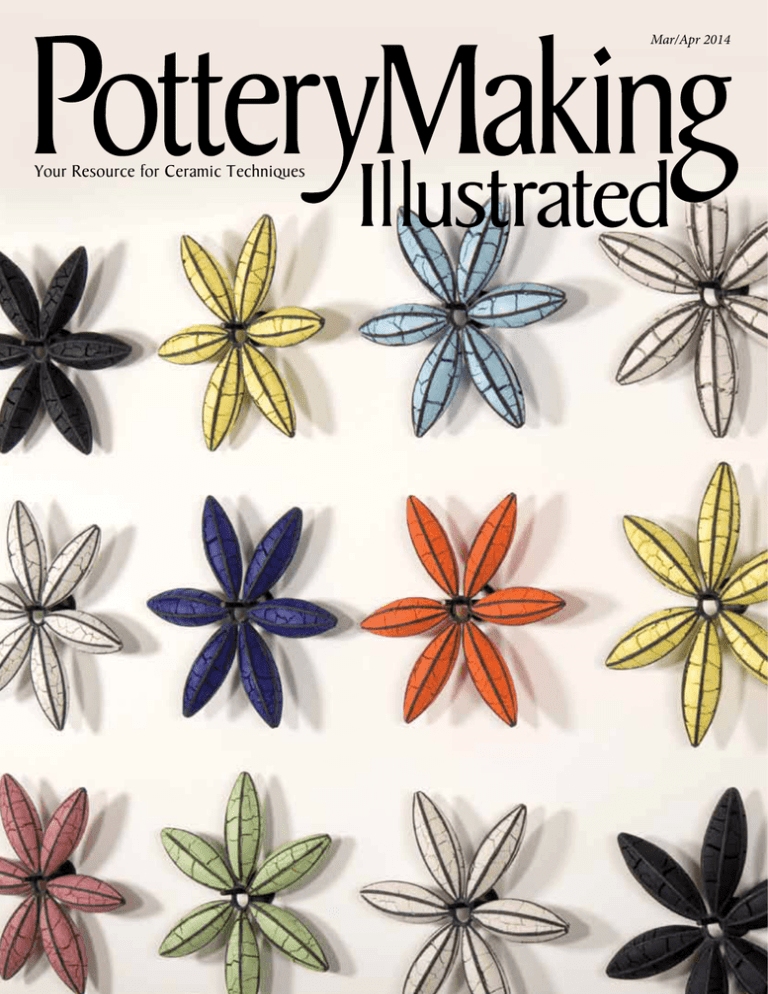

On the Cover Deb Sigel’s Flowers, 20 in. (51 cm) in diameter,

Egyptian Paste, steel armature. Photo: Brian Giniewski.

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

3

fired up | Commentary

Volume 17 • Number 2

Breaking Out

Publisher Charles Spahr

Editorial

Editor Bill Jones

Managing Editor Holly Goring

Associate Editor Jessica Knapp

Editorial Support Jan Moloney

Editorial Support Linda Stover

Creativity involves breaking out of established patterns in order to look at things in a different way.

—Edward de Bono

When it comes to setting fire to your creativity, nothing

works better than breaking a few rules. Why settle for repeating a tried-and-true technique when you can try something

new that pushes you out of your comfort zone? Since Pottery

Making Illustrated prides itself in uncovering the offbeat and

unusual, you’ll enjoy some of the techniques in store with this issue.

The first thing you’ll notice is that the cover and feature article deal with Egyptian

paste, a self-glazing clay that Deb Sigel uses in a very creative way. Author Mary Cloonan

describes how, after fabricating metal frames, Sigel pushes the paste into place and fires

the pieces, before they dry, to cone 05. The colors, cracking, and black framework all

work together for her sculptures, but think of her process as a starting point—what

would you do with Egyptian paste?

If you’re looking for different decorating ideas, check out Shana Salaff ’s pattern ideas,

Robert Balaban’s brick façades, or Bryce Brisco’s slip technique. For handbuilding, Marty Fielding’s oil bottle process provides the basis for dozens of forms as does WangLing

Chou’s plastic-bottle molded teapot. And for our continuing series, Sumi von Dassow

delights us with an egg separator and a delicious recipe for lemon meringue pie, Deanna

Ranlett shows the possibilities of recycling old shop glazes into beautiful new ones, while

Robin Ouellette illustrates different brush types and their uses in her latest Pottery Illustrated segment.

All of our contributors develop their techniques after many attempts to get to the

place they want to be, but in doing so, what they describe becomes established. Your

challenge is to break out and build upon what they’ve learned, taking the knowledge

they share to create your own path.

On another note, we’re pleased to announce a few changes to the staff here as Holly

Goring transitions to Managing Editor in charge of most all editorial functions of the

magazine. She’s backed up by Jessica Knapp for editing and acquisitions as well as Melissa Bury and Erin Pfeifer providing design and graphic production. Over the past few

years, Holly and Jessica have worked diligently to bring you some of the best techniques,

and I’m confident the magazine will continue to improve through their efforts.

Bill Jones

Editor

editorial@potterymaking.org

Telephone: (614) 895-4213

Fax: (614) 891-8960

Print and Digital Design Melissa Bury

Production Associate Erin Pfeifer

Marketing Steve Hecker

Circulation Manager Sandy Moening

Ceramics Arts Daily

Managing Editor Jennifer Poellot Harnetty

Webmaster Scott Freshour

Advertising

National Sales Director Mona Thiel

Advertising Services Marianna Bracht

advertising@potterymaking.org

Telephone: (614) 794-5834

Fax: (614) 891-8960

Subscriptions

www.potterymaking.org

Customer Service: (800) 340-6532

potterymakingillustrated@pubservice.com

Editorial and Advertising offices

600 N. Cleveland Ave., Suite 210

Westerville, OH 43082 USA

www.potterymaking.org

Pottery Making Illustrated (ISSN 1096-830X) is published

bimonthly by The American Ceramic Society, 600 N. Cleveland Ave., Suite 210, Westerville, OH 43082. Periodical postage paid at Westerville, Ohio, and additional mailing offices.

Opinions expressed are those of the contributors and do not

necessarily represent those of the editors or The American

Ceramic Society.

Subscription rates: 6 issues (1 yr) $24.95, 12 issues (2

yr) $39.95, 18 issues (3 yr) $59.95. In Canada: 6 issues (1

yr) US$30, 12 issues (2 yr) US$55, 18 issues (3 yr) US$80.

International: 6 issues (1 yr) US$40, 12 issues (2 yr) US$70, 18

issues (3 yr) US$100. All payments must be in US$ and drawn

on a U.S. bank. Allow 6–8 weeks for delivery.

Change of address: Visit www.potterymaking.org to

change your address, or call our Customer Service toll-free at

(800) 340-6532. Allow six weeks advance notice.

Back issues: When available, back issues are $6 each, plus

$3 shipping/handling; $8 for expedited shipping (UPS 2-day

air); and $6 for shipping outside North America. Allow 4–6

weeks for delivery. Call (800) 340-6532 to order.

Contributors: Writing and photographic guidelines are

available on the website. Mail manuscripts and visual materials to the editorial offices.

Photocopies: Permission to photocopy for personal or inter-

nal use beyond the limits of Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S.

Copyright Law is granted by The American Ceramic Society,

ISSN 1096-830X, provided the appropriate fee is paid directly

to Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Dr., Danvers, MA 01923; (978) 750-8400; www.copyright.com. Prior

to photocopying items for educational classroom use, please

contact Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

This consent does not extend to copying items for general

distribution, for advertising or promotional purposes, or to republishing items in whole or in part in any work and in any format. Please direct republication or special copying permission

requests to the Ceramic Publications Company, The American

Ceramic Society, 600 N. Cleveland Ave., Suite 210, Westerville,

OH 43082.

Postmaster: Send address changes to Pottery Making Illustrated, PO Box 15699, North Hollywood, CA 91615-5699.

Form 3579 requested.

ceramic arts dail y.org

Copyright © 2014 The American Ceramic Society

All rights reserved

4

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

5

in the studio | Glaze

One Man’s Trash

by Deanna Ranlett

One man’s trash is another man’s treasure. That’s the sentiment

echoed recently in our studio while re-mixing leftover shop glazes together. It’s a fairly common practice in large studios to make

what’s called a “trash glaze” using the remaining bits of various

shop glazes to avoid throwing glaze materials down the drain.

While researching online how to safely dispose of glaze materials, I found a number of suggestions from firing the materials

inside bisque bowls to a low temperature to sinter them to adding recycled clay then shaping the mixture into bricks or tiles and

firing them. Many large studios also utilize hazardous materials

bins that are delivered by their local waste management departments. Personally I believe that the best bet is either the latter

option or to reuse the materials as trash glazes.

Rescuing Trash Glazes

Bucket B with 5 Modifications

Bucket A with 5 Modifications

When making trash glazes, the result is commonly dark gray,

dark brown, or dark blue because of the various coloring oxides combining from all of the glazes. One technique is to mix

together glazes of a similar nature, for example, mixing leftover

6

clear glazes together, light colors with other light colors, and

blues with greens, etc. For our group studio experiment, we

chose glazes at random as if you were just cleaning up or retiring some older unwanted glazes. Often studios are not thrilled

with the resulting colors of their studio trash glazes so we decided to also experiment with small additions of modifiers and

opacifiers to show some remedies for rescuing a trash glaze. I

selected titanium dioxide, rutile, Zircopax, zinc oxide, and iron

oxide as additives.

Testing for Food Safety

It’s important to test for leaching in the resulting glazes although general consensus says that because of the variety of

fluxes present, trash glazes are usually very stable. Performing

a basic lemon or vinegar leaching test is the proper thing to

do when mixing and firing any new glazes. Allow your fired

glazed piece to sit for at least 24 hours with a lemon slice on it

or partially submerge it in vinegar to show if color is leaching

from your glazes.

Figure 1

Bucket A Base

Figure 3

2% Titanium

Figure 5

2% Rutile

Figure 7

2% Zircopax

Figure 9

2% Zinc

Figure 11

2% Iron

Figure 2

Bucket B Base

Figure 4

2% Titanium

Figure 6

2% Rutile

Figure 8

2% Zircopax

Figure 10

2% Zinc

Figure 12

2% Iron

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

Initial Glaze Tests

Conclusions

Bucket A was a mix of five cone-6 glazes:

dark green, white, purple, dark blue, and

celadon. This group of tests were done

on tiles made from Helios porcelain

from Highwater Clays, and fired to cone

6. This glaze fired to a translucent gray.

Overall, bucket A had more variation

among additives (figure 1).

Bucket B was a mix of five cone-6 glazes: dark brown, white, cream, black, and

powder blue. This group of tests were

done on tiles made from Red Rock stoneware, also from Highwater Clays, and fired

to cone 6. The glaze fired to a dark floating

blue. Overall, bucket B had less dramatic

results among additives (figure 2).

For trash glazes, my approach would be to

first add Zircopax to lighten and brighten

the color. Our bucket A made a lovely,

neutral gray on its own that many studio

members wanted to try. Adding titanium

dioxide or rutile also made a lot of sense

because you’re able to produce reductionlike effects with glazes that have variegated, hares-fur type textures on their surfaces. The addition of zinc oxide gave the

most interesting variation (although difficult to see in the photos.) It added more

Adding Glaze Modifiers

• 2% titanium dioxide gave a variegated

surface with bright color. In both glazes,

the titanium dioxide brought out the cobalt. Bucket A, which initially was a dark

gray, came out a soft floating blue that

broke green (figure 3). Bucket B, which

already appeared as a floating blue had

more crystals and a softer color (figure 4).

• 2% rutile yielded a variegated surface and

brightened the color, adding more green

hues. It also opacified the glaze a bit more

than the titanium dioxide did. The glaze

from bucket A resulted in a beautiful

soft powder blue (figure 5). Bucket B had

almost no change from the original tile

with the addition of the rutile (figure 6).

• 2% Zircopax gave the glazes a boost in

brightness. This was expected because

Zircopax is an opacifier used to make

glazes lighter and whiter. The glaze

in bucket A became a brighter, more

opaque, and green gray (figure 7). The

glaze from bucket B became a softer,

more cobalt-hued floating blue and

broke less around the textured areas

(figure 8).

• 2% zinc oxide gave the glazes what we

called a “starry” quality. The glaze from

bucket A became a pale gray with darker blue pools of tiny crystals (figure 9).

The bucket B test had a similar starry

effect and an even brighter blue where

the glaze pooled (figure 10).

• 2% iron oxide gave the glazes a deeper

brown hue as expected. I would view

adding iron as a “black out” effect if you

aren’t happy with the original color of

your trash glaze and just want to create

a rich deep brown (figures 11–12).

flux, which resulted in a nice break on the

texture and a star-like effect.

When working with trash glazes, I

would suggest making changes in small

increments and firing in between to test.

Because of the variety of oxides, opacifiers, and ingredients, small changes and

additions are all that are needed to make

a large impact.

Deanna Ranlett owns Atlanta Clay

(www.atlantaclay.com) and MudFire Clayworks and Gallery (www.mudfire.com). She has

been a working ceramic artist for 13 years.

“My Paragon

kiln practically

fires itself,

giving me more

time to make

pots” —David

Hendley

The Paragon kiln was already

ancient when David and Karen

Hendley bought it in 1995. Since

then David has fired about 20,000

pieces of bisque in his electric

Paragon.

“For the last 20 years I have

been glaze-firing all my work in a

wood-fired kiln,” said David. “I

enjoy the excitement of the firings,

and my friends and customers like

the random fire flashings and ash

deposits.

“What they don’t know is that

every piece is first fired in my Paragon electric kiln. While accidental and chance effects can enhance

a wood firing, consistency is the

key to successful bisque firings.

“For those firings, my Paragon

has delivered reliable and consistent results year after year. It practically fires itself, giving me more

time to make more pots.”

The Paragons of today are

even better than the early ones.

The digital 12-sided TnF-27-3

shown at right is only 22 ¼” deep

for easier loading. Lift the lid effortlessly with the spring counter-balance. Enjoy the accuracy

David and Karen Hendley with their ancient Paragon

A-28B. It has fired about 20,000 pieces of bisque. The

Hendleys run Old Farmhouse Pottery in Maydelle, Texas.

and convenience of the

Orton controller.

To learn more, call us

or visit our website for a

free catalog and the

name of the Paragon

dealer near you. Sign up

for the Kiln Pointers

newsletter.

Join the Clayart pottery forum here:

lists.clayartworld.com

Constantly finding better

ways to make kilns.

2011 South Town East Blvd.

Mesquite, Texas 75149-1122

800-876-4328 / 972-288-7557

Toll Free Fax 888-222-6450

www.paragonweb.com

info@paragonweb.com

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

7

in the studio | Surface Decoration

Brick Façades

by Robert Balaban

I was commissioned to make a mug as a going-away present

for an architect. Since he worked primarily on a series of brick

buildings built during the 1960–1980s. I decided that a classical

red-brick construction or brick façade would be an appropriate

design surface for this project.

I looked for brick molds I could use to make reasonably sized

sheets of brick façades. I found that the best sources for these

molds were from the baking industry. The most useful molds

were ones used for fondant decorating, which provided a crosssection of choices for my project. A couple of sources for these

molds (and many other designs) include www.nycake.com and

www.jubileesweetarts.com—they’re remarkable in variety and

high quality.

The molds for bricks come in two forms, large and small rollers

for impressing texture, or simple plastic sheets for press molding

(figure 1). After experimenting, I found that a sturdy sheet mold

for press molding worked the best, providing a reproducible pattern and a large enough sheet to work as a façade or as an actual

slab for construction. I had difficulty getting consistent pressure

with the rollers, resulting in uneven impressions.

1

Cake decorating rollers and panels. Apply

a release agent then press into a clay slab.

3

Clean the join. Brush on a contrasting

clay slip over the façade. Be sure to fill all

of the grooves.

8

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

Finished piece with added brick façade and white stoneware

clay slip.

2

Cut either uniform or irregular shapes to

use as slab construction or decoration.

4

Allow the ware to dry, then gently scrape

off the white clay slip revealing the brick

and mortar pattern.

3

Score and slip the two pieces, then join

together. Be sure to press out air pockets.

5

Surface detail of a finished and fired

brick and mortar façade.

Pressing the Mold

Start by coating the mold with a releasing agent (silicon spray from Liquid

Wrench works well), then roll out an

even clay slab to about 1⁄3 inch thick for

decorative façades and 2⁄3 inch thick for

slabs for building walls. Generally, red or

terra-cotta clay bodies with a little bit of

grog look good for this project, although

some stoneware clay bodies may work as

well. Working on a flat absorbent surface,

smooth and compress the slab with a rib,

then press the mold firmly onto it. After

releasing the mold, let the slab firm up

a bit on a canvas-covered plaster slab to

prevent deformation during application.

You want the material pliable enough

to bend without cracking but not easy

to deform with modest finger pressure.

I found that cutting irregular structures

from the slab generated a more interesting result for a simple mug (figure 2).

façade back in place without additional

cracks forming.

Allow the ware to dry, then gently

scrape off the white clay slip, revealing

the mortar grooves (figure 5). Caution:

Always wear a mask when scraping dry

clay and use a wet sponge to clean up

the scraps. It’s important to let the ware

almost reach the bone-dry state to prevent smearing of the red brick clay over

the white clay mortar grooves. With

a little practice, you can find what extent of drying works best to make the

scraping easier while avoiding smearing, however bone dry works well even

though it requires a bit more effort.

I like to keep the brick surface unglazed so after the bisque firing, I brush

wax resist over the façade to keep the

exterior and liner glazes off of it. The

result, after the glaze firing, is a very attractive surface that closely simulates a

natural brick structure.

Robert Balaban is a functional potter and

teaches classes in his studio in Maryland.

Decorating with Press Molds

Attach the still moist but firm brick façade to a leather-hard vessel by scoring

and slipping both parts then attaching

(figure 3). You may need to touch up any

areas damaged during the application.

It’s important that the mortar grooves

are retained through this process for

filling in later steps. Note: The vessel

the façade is being attached to and the

clay slip must have similar shrinkage to

prevent the façade from separating from

the vessel. If you use two different clay

bodies, use extra care when attaching

them to avoid cracking or separating

during drying and firing.

Once the façade has firmed to leather

hard on the ware, apply a white stoneware clay slip over the entire façade to

fill the mortar grooves (figure 4). Again,

the white slip must match the other

clay’s shrinkage rate. I let the first coat

firm up, then add a second and sometimes a third coat of white clay to ensure

I have filled all of the mortar groves. If

you can still see the brick pattern after

applying the white clay, you need to add

another coat.

During the drying process, small edges of the façade may pull away from the

vessel. I find that by waiting about ten

minutes for the surfaces to soften after

applying a wet clay slip between the

façade and vessel, I then can press the

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

9

in the studio | Carving

Building Big, Carving Deep

by Barbara Stevens

I came to brick relief carving later in my ceramic career after participating in a large-scale, public art project based on wet brick

carving. I loved being able to use clay and work BIG. It was also

at this time that I learned to carve sculptures that could also be

used as benches. My first carved brick bench was so exciting, and

I enjoyed working with 12×8×4-inch solid bricks that allowed

me to apply heavy texture and have up to five inches of relief.

Planning a Large-Scale Outdoor Brick Bench

Start with sketches of a bench design, use a theme or a pattern to

make up the seat, back, and arms then carve a maquette. Sketch

the outside ring of each brick layer, then number the layers as

well as the individual bricks, which determines the exact dimensions of the bench and how many bricks you need. Order the

unfired, wet brick from a local factory, either have them delivered or pick them up yourself depending on what’s convenient

1

Stack the wet brick to form a bench. Use

the maquette to sketch on the design.

4

Label each brick with a number and the

layer it’s in. Make notes of the labels.

10

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

for you. Clear a large indoor space to work and cover the floor

with plastic. Start by stacking the outside ring of bricks in layers

to match your sketches. The center bricks are only used to form

the stack so that the seat has support during this carving process.

They’re not counted in the numbering process, nor are they fired.

The outside ring must form a box and these bricks need to be alternated to form a sound structure. While stacking, alternate the

direction of the bricks on each layer so that the seams alternate

by one half brick, ensuring a strong and durable structure.

Deep Carving

Using the maquette, draw your design on each side of the stack

(figure 1), then start carving the deepest areas first. An easy way

to remove large hunks of brick is with a wire cutter (figure 2).

This is much faster than using a loop tool, which works better for detailing. Once the deep grooves are in place and the

2

Remove large sections of wet brick with

a wire cutter to quickly define the form.

5

Choose a mortar color to match the fired

brick for a cohesive looking bench.

3

Use loop tools to add texture and details. Cover the brick when not carving it.

6

Barbara Stevens’ finished sunflowerthemed bench.

design starts to take shape, begin the texturing, detailing, finetuning, and burnishing to complete the bench sculpture (figure

3). Remember to mist the bricks with water several times while

carving and before covering with two layers of plastic after each

carving session to keep them wet for the duration of the project.

Label the Brick

After the sculpture is complete, the wet brick must be numbered and stamped as the brick layers are taken down. This is

important because the bricks are handled many times from

start to finish. To ensure that you can recreate the bench without

too much confusion, make several drawings, take plenty of photos, and make notes on the bricks themselves. Label each brick

with its layer number and an individual brick number. I use a

hammer and heavy metal stamps to inlay numbers on the bricks

(figure 4) making them easy read after they’re fired. I also draw

an arrow on each brick showing which direction the brick lies in

that layer.

Drying and Firing the Brick

To aid the drying process, drill holes into the back of the brick,

leaving an inch of space between the holes and the carved edges.

Three holes per full-sized brick is sufficient. Place the bricks

on pallets with space between them for good air flow and even

drying. Keep them away from any draft or lay a piece of plastic

lightly over the top of each palette. The bricks may take several

weeks or longer to dry completely depending on your climate.

Fire the bricks in individual layers with plenty of space between the kiln shelves. Do not overcrowd the kiln and note that

the firing may take longer due to the larger masses requiring

more heatwork.

Reconstructing and Installing the Bench

Lay the fired brick in rows according to their respective layer

and number. Next, arrange the layers as they would be installed

on the bench so they match the drawings and photos.

I hire a mason to install my large benches and recommend doing this unless you have masonry skills. Together we lay out layer

A (the bottom layer) and square it on the cement base, which is

laid ahead of time to support the sculpture. Next, mix the masonry cement with mason dye to match the brick, and start installing the first layer. From there, it’s just a matter of laying the

next three layers before filling the seat cavity with cut cement

block and cement to support the seat. The cavity needs to set up

and dry before the seat can be installed.

To complete the bench installation, stack a few layers of the

arms and the back to make sure they line up with the base (figure 5). Adjustments may need to be made but as long as they’re

minor they can easily be fixed with some creative mortar work.

My finished bench looks great outside my studio and will

hopefully inspire more brick sculptures (figure 6).

Thank you to my ceramic professor Darrell McGinnis, St. Louis ceramic

artist Catharine Magel, and Seattle brick carver Mara Smith for their

training and inspiration in teaching both ceramics and brick carving.

Barbara Stevens works and lives in Concordia, Kansas. To see more of her

brick carving, check out http://ccccartstars.blogspot.com/2011/10/sunflower-bench-fall-2011.html.

Now your wheel

can multitask.

GlazeEraser is a unique, slow speed grinding

tool designed to work with your potter’s wheel

to quickly remove glaze drips and other unwanted

kiln debris from pot bottoms. Ideal for quickly

smoothing foot rings and rough glaze edges.

Order online at GlazeEraser.com

Visit us at NCECA booths 235-237

View demo at GlazeEraser.com/video

Manufactured by:

Call Toll Free: 1.866.545.6743

Visit www.GlazeEraser.com

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

11

by Shana Salaff

Patterns have embellished ceramic objects since our Neolithic

past. Early clay vessels often imitated woven baskets. Our fascination with pattern and decoration dates back even further.

We take pleasure from our environment when it’s enhanced

with decoration.

Theorist Ellen Dissanayake states that the evolutionary origin

of art making is connected to our early development as a species.

Then, as now, the intimate connection a baby has with its parents

is crucial to language and behavior development. Sustaining this

depth of feeling later in life is at the root of our drive to elaborate upon our material world. Dissanayake coined the phrase

“making special” to describe the human impulse to change one’s

natural surroundings or built environment through any form of

artmaking. When present-day potters decorate their work, they

are joyful participants in this making special. Pattern is a great

way to achieve this.

The What and Why of Pattern

Pattern divides a visual surface into regular intervals with the repetition of individual elements. While these elements can be anything, the organizing principle of repetition brings unity to the

design. What do we see when we look at pattern? In an abstract

pattern, we see a rhythmic arrangement of lines, shapes, and

movements. When patterns contain representational elements,

this adds another layer of meaning. For example, a floral pattern

evokes natural beauty, while other imagery causes us to call up associations with things we have seen before. When beautiful line

quality, surface variation, and color are brought into the mix, a

pattern becomes much more than just a way to organize space.

Patterns also have historical resonances (derived from our own

culture or that of others), which many ceramic artists use to their

advantage. Using a pattern inspired by historical ceramics on the

surface of a contemporary piece adds a layer to the visual experience. In the finished piece, this layer can then be compared with

the form it sits upon, made either within the same historical refer12

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

ence or in contrast to it. Using patterns from another culture or

time period is acceptable, as long as you treat both the culture and

the pattern with respect in an attempt to find your authentic voice.

Using copyright-free patterns is the safest way to do this.

Pattern Sources

I often decorate my work with components of patterns pulled

from various historical sources. Most of the patterns I use on a

regular basis come from the library’s visual art section. I choose

a specific pattern for the aesthetic pleasure I find in it, as well

as how easily I can transform it into a fresh decorative surface.

I also look for flowing lines, a pattern that moves well across

the surface, and lovely, small floral or leafy elements. I find

Victorian wallpaper patterns easy to use because of the plant

and flower designs (figure 1). I have adapted Chinese patterns

derived from rugs with the same quality (figure 2). For line

work, I prefer patterns that have a movement across space like

a swooping line or draped arrangements of leaves on a stalk. I

will shuffle through my extensive collection of patterns when

considering a new form or new material. However, I am usually

drawn to the same two or three.

I’m working with pattern as a tool, using it as a framework for

beautiful line quality and color variation, and applying a painterly filter. There is a difference between a pattern created to fit

a specific form (such as around the rim of a plate) and pattern

used as a surface decoration on a form more like paint on canvas.

I am not imitating the pattern but using it as a framework and

vehicle for self-expression. The historical reference hovers in the

background waiting to be recognized. This is my own way of using pattern to make special.

Transferring a Pattern

I copy patterns onto acetate and project them onto my work with

an old overhead projector. I first started using one because I mistrusted my ability to draw freehand. Now, using a projector allows

me to concentrate on line quality and spacing because I don’t have

to worry about getting it right. For a pattern from a book, this involves scanning the page onto my computer, sizing it, tiling it (creating a repeating pattern), then printing it onto transparency film

(use the kind appropriate for your printer or have it done for you

at an office supply store). Another option is to trace onto acetate

directly from a visual source such as a printed textile. You might

have to scan this in order to shrink the image for projection. You

can find old overhead projectors in thrift shops or online: look for

ones that contain working bulbs, as these are the most expensive

items to replace. Projectors that connect directly to a computer

also work but are more expensive. If you prefer not to use a projector, take time to practice drawing your pattern with pen and

paper so you can have the same fluency with your hand as you

would tracing a projection. There are also many ways to transfer a

paper pattern onto clay. Search for “image transfer techniques” on

ceramicartsdaily.org for more information.

Developing a Personal Vocabulary

Give yourself the following assignment for developing a personal vocabulary with pattern: Experiment with a few patterns

and a large number of materials. Create a large number of simple

1

Wheel-thrown and altered cup with incised elements of a William Morris wallpaper pattern layered with a diamond pattern.

tumbler shapes—they make a simple canvas to work with—that

need little or no trimming, or that can be easily handbuilt. Alter

into thirds or square off the form if you like (figure 3). Choose

or create two or three patterns to play with. Assemble all your

decorating equipment and materials and get ready to play with

variations. Commit to making each surface different.

Use an X-Acto knife to carve patterns onto about one-third to

one-half of your cups (figure 4). Experiment with different portions of the pattern, proportions of the surface, and any other

variable that you can think of. Use the uncarved cups for underglaze application before or after bisque, as well as glaze application (figure 5). Try every combination of materials you have

access to, as well as every decorating technique you can think

of: sgraffito, underglaze- or glaze-trailing, brushing, waxing

and wiping away, inlaying slip or underglaze into carved surfaces when leather hard or over bisque, adding layers of glaze,

glaze pencil, or overglaze. Invent your own techniques, and play

with color, texture, value, type of line, etc. Layer techniques and,

whenever possible, contrast one pattern with another (figure 6).

Experiment with ways to work with the negative space around

the pattern as much as the pattern itself (figures 7 and 8).

2

Wheel-thrown and altered cup with a carved and glazed lotus

pattern over a glazed diamond pattern.

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

13

process | Pattern and Meaning | Shana Salaff

3

Alter a cylinder to create different planes

or sections (either vertical or horizontal)

to start to organize your design.

6

Brush on glaze to create a second pattern. Use a resist on the first pattern if

you wish to keep the glazes separate.

4

Project a pattern onto the cup, arrange

the composition, and carve or trace

around the edges of the projected shapes.

7

Other ideas for making your own pattern are to go out and draw

trees or flowers, walk around your neighborhood, find decoration

you love, look in your closet for patterned fabric, photograph it,

tile it on your computer, etc. If you’re like me, obsessed with historical patterns and wallpaper, find copyright-free examples. Ask

yourself: how do you want to use pattern? Where do you find, or

how do you create, your pattern? How do you want to make your

work special? Playing with the answers to these questions will help

you create your own voice when using pattern in your work.

Great resources for pattern ideas include Owen Jones’ texts The

Grammar of Ornament, and The Complete “Chinese Ornament.” In

these, Jones illustrates precise and beautifully rendered examples

of ornament and pattern from around the world and across centuries. Jones was one of the mid-19th century thinkers who participated in the intense cataloguing of both the natural and human

world in the search for underlying theories and rules.

I prefer to ignore strict pronouncements about what is “correct”

or even “best” and proceed on the basis of intuition. Use your inPotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

Apply underglaze or glaze with a slip

trailer or a brush using the projected image as a guide.

8

A Chinese cloud pattern created using

glaze. The negative space becomes an

active part of this composition.

Investigating Further

14

5

The same cloud pattern, carved into the

surface, glazed, then overlaid onto a diamond pattern for a different visual effect.

tuition to guide you toward self-expression. Ultimately, this will

grow out of continued exploration into what moves you as a person as well as an artist.

Shana Salaff lives in Fort Collins, Colorado, where she teaches at Front

Range Community College in Fort Collins, and Aims Community College

in Greeley, Colorado. She earned an MFA in ceramics from California State

University, Fullerton. She has also written for Ceramics Monthly magazine.

To see more of her writing and her artwork, visit www.shanasalaff.com.

Suggested Reading

Dissanayake, Ellen. 2000. Art and Intimacy: How the Arts Began.

Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Dissanayake, Ellen. 2002. What is Art For? Seattle: University of

Washington Press.

Owen Jones; foreword by Jean-Paul Midant, L’Aventurine. ca.

2006. The Grammar of Ornament: Illustrated by Examples from

Various Styles of Ornament.

Owen Jones (1809-1874). 1990. The Complete “Chinese Ornament”: All 100 Color Plates. New York: Dover.

America’s Most Trusted Glazes

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

Kelley Donahue

Chandra DeBuse

Bonnie Seeman

Tom Bartel

Kensuke Yamada

Ben Carter

Molly Hatch

Ryan Takaba

Meredith Host

Zach Tate

Deborah Schwartzkopf

Amy Smith

Brett Kern

2014 NCECA Gallery

www.amaco.com/nceca-2014

15

Olympic FL12E

Inside dimensions 24”

x 24” x 36”, 12 cu. ft.,

fires to 2350°F –

Cone 10, 12 key

controller with cone

fire & ramp hold

programming, 240-208

volt, single phase.

$5710

Olympic DD9 with

Vent Hood* – Inside

dimensions 30” x

25” x 25”, inside

volume 15 cu. ft.,

setting area 23” x

23” x 30”, 9.2 cu.

ft., fires to 2350°F –

Cone 10, propane

or natural gas

$5870

* Pictured with optional

stainless steel vent hood

16

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

For less than $6,000,

you could be firing a 12 cubic foot,

cone 10 gas or electric kiln.

More value for your dollar,

more bang for your buck!

Contact an Olympic Kilns Distributor to

purchase an Olympic Gas or Electric Kiln

www.greatkilns.com

Phone 800.241.4400 or 770.967.4009

Fax 770.967.1196

Bryce Brisco

The Art of

Serving

by Yoko Sekino-Bové

Bryce Brisco is a ceramic artist currently working and teaching as an

artist-in-residence at the Appalachian Center for Craft in Smithville,

Tennessee. His functional wood-fired tableware, like the shallow bowl

he demonstrates decorating here, is adorned with simple (yet elegant)

slip patterns, resist elements, and incised texturing. Just like Bryce

himself, his work is sincere, durable, and inviting.

Bryce uses a light gray, smooth stoneware clay body of his own creation that’s comprised of local clays he digs up in the area around

Smithville. By using local materials, he’s able to establish a relationship with the region’s people and give the pots an identity based on the

area’s culture. He enjoys the unpredictable beauty of these local clays

when wood fired in a salt atmosphere.

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

17

process | Bryce Brisco: The Art of Serving | Yoko Sekino-Bové

Materials

n Circle

templates

liner contact paper

n Long, skinny brush dedicated

for food-color painting

n Circles hand cut from

contact paper

n Food color

n A clear, CD-shaped plastic

disc (when you buy a CD pack,

this plastic disc protects the

actual CDs), with permanentmarker guidelines added to it

to indicate angles.

n Shelf

1

Making, then refining the rim of a shallow bowl with a rubber rib.

2

Drawing a circular guideline with food

coloring on the soft, leather-hard bowl.

Throwing a Shallow Bowl

Bryce throws his pieces using minimal

tools. After using three pounds of clay

to create a 10-inch-diameter bowl with

a smooth inside curve and a rim that’s

about two inches wide, he cleans the surface with a rib before applying any surface decoration (figure 1). He does not

cut the clay from the bat immediately

after throwing, leaving it attached keeps

it centered for the decorating stages.

Depending on his studio schedule, he

either leaves the bowl for a day to naturally dry the surface, or he uses a torch

to remove the moisture quickly. When

the surface has lost its sheen, the bowl is

ready to be decorated.

Applying Stickers

Bryce works with both slip and resist

surface techniques. He cuts several circles out of contact paper with scissors

before starting to work on the clay. The

contact paper is water-proof and resistant to slip. He wants to keep these circles hand-cut. “I know we can buy circle

stickers, but mechanical perfection does

not work on handmade pots. People can

tell the difference.”

18

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

3

Applying marks for three dividing lines

using the homemade measuring tool.

4

Completing the guidelines after removing the dividing tool.

When the bowl dries to soft leather hard, he places the bat back on the wheel and

paints on a series of circular lines as guides using food coloring. Because the food

coloring burns out at a very low temperature without leaving residue, these guidelines

don’t affect the final result (figure 2).

The next step is to mark three, evenly divided lines for three of his circle stickers. To

do this, Bryce uses a guide made by marking a clear compact disc with dividing lines

(the disc shown has marks for dividing a surface into three or five segments). He holds

the disc above the circular lines, positions it as close to the center of the bowl as he can,

and marks where his lines will go using food coloring (figure 3). Using this method, he

can measure the spots for the stickers very evenly.

After removing the blank disc, he paints in the guidelines for the stickers and rechecks the distance between them by eye (figure 4), then, following the guidelines, he

applies three contact paper stickers (figure 5).

Pouring White Slip and Finger Swiping

Bryce keeps a big bucket of white slip on hand to decorate multiple larger forms.

He removes the pot (still attached to the bat) from the wheel, and pours a generous

amount of the slip into his bowl (figure 6). He swishes it around the interior to make

5

Applying water-proof circles, centered over the dividing lines

and between the concentric circular guides.

7

6

Pouring slip into the bowl, over the resist circles, then swishing

it around to coat the interior, then pouring out the excess.

8

Wiping and cleaning the rim using a rubber rib before the added

slip softens the bowl too much.

Drawing a sgraffito finger swipe through the slip that interacts

with the resist circles.

sure it covers the entire inside curved area, then pours it out,

back into the bucket.

Placing the pot back on the wheel, Bryce cleans up the rim with

a rib and removes any splashes created by the slip immediately after pouring the slip out, before the clay gets soggy (figure 7).

Now he uses his finger to swipe at the surface to create a

loose, thick line (figure 8). The secret is to relax, stop thinking

too much, and enjoy the process, stopping when the pattern or

composition of lines looks complete.

While turning the pot slowly on a wheel, Bryce gently presses

the texturing tool against the rim to incise the pattern. At this

point, the clay is still soft enough to be carved, but firm enough

to support itself. He doesn’t need to support the underside of

the rim while creating the pattern (figure 9).

Once the decoration is completed, the contact paper dots are

removed (figure 10), then the pot is trimmed and dried prior to

being prepared for glazing.

Decoration on the Rim

Bryce’s incised texture pattern on the rim was inspired by Tatsuzo Shimaoka, the respected Japanese potter who used a piece

of rope to create incised patterns. But as always, Bryce found

his own way to create a similar effect with a handmade tool

sourced from a hand-cranked/manual pencil sharpener. For

this texturing, he uses the part of the pencil sharpener that actually spins and grinds the pencil.

Prepping for Firing

Bryce does not bisque fire his work. The white, slip-covered

area of the pot is glazed with a clear glaze when the pots are

bone-dry, leaving the areas that were covered by the stickers

unglazed so he can place seashells and clay/alumina wads there.

These wads create a decorative surface effect, while also allowing him to place one more piece on top of the wads, so he

can fit more work into a kiln (figure 11). He fires the pots in a

wood-burning salt kiln up to cone 11 (figure 12).

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

19

process | Bryce Brisco: The Art of Serving | Yoko Sekino-Bové

9

10

Applying a texture to the rim using part of a manual

pencil sharpener.

Using a sharp needle tool or X-Acto knife, lift up and remove the

contact-paper circles.

11

12

Placing alumina and clay-stuffed shells onto the circled spots on

the dry greenware bowl and stacking an additional piece on the

shells before firing.

Bryce’s white slip recipe

Bryce’s wadding seashells

Cone 11

Cone 11

Tile 6 Clay . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 00%

Add:Bentonite . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2%

Alumina Hydrate. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50%

EPK Kaolin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50%

Bryce adjusts the base recipe by adding varying

amounts (between 2 and 10%) of Zircopax,

Grolleg, feldspar, and/or silica to the bucket to

change the opacity, whiteness, melt, and fit of the

slip, respectively. This is a loose recipe for a big

portion, just like a home cooking recipe.

Mix the alumina and EPK kaolin with water until

workable, then stuff the wadding inside each

seashell prior to placing the shells onto the pot.

Yoko Sekino-Bové is an artist and teacher living in Washington, Pennsylvania.

To see more of her work, visit yokosekinobove.com.

20

Completed plate showing the wad marks from the aluminafilled seashells, and the effects of the salt-firing on the piece,

including the sheen on the rim.

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

ar

ye

ww

aarr

rraa

nnttyy

oop

pti

tio

onna

all le

leg

g

10

e

ex

xtte

en

nssiion

onss)

)

ate

eb

er

az

$

$110

00

0A

AM

MA

AC

CO

O®®

ggll

((

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

21

Push/Pull

The Art of Deborah Sigel

by Mary Cloonan

Detail of Burst, 26 in. (66 cm) in height, Egyptian

paste and steel. Photo: Brian Giniewski.

22

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

process | Push/Pull: The Art of Deborah Sigel | Mary Cloonan

where, in addition to studying ceramics, she spent a lot of time

in the metals studio and interacted with other students in both

areas. Egyptian paste, or faience, is a low-fire mixture of ceramic materials containing clay, sand, colorants, frits, and soluble

salts. These salts effloresce to the surface along with water as the

paste slowly dries, forming crystals, which create a self-glazing

clay-glaze hybrid once fired. As the name implies, it was originally developed in Egypt and was used to mimic semi-precious

stones such as turquoise or lapis lazuli.

Intrigued by the property of the glassy paste and the opportunity to build sculpturally with color she explored its characteristics. Initially, she experimented, creating steel cages to hold

Process photos: Hannah Watson

There is a discordant beauty inherent in Deborah Sigel’s work.

The black steel framing the deep cracks in the Egyptian paste

seem at odds with the bright colors and botanical forms. It’s

this dichotomy; order and chaos, stoic and friendly, that entices and intrigues. Viewing her work poses questions about the

nature of beauty in imperfection, the clash of industrial with

organic elements, as well as how the pieces were made. Sigel

pushes the rules and limits of the materials she uses while pulling the viewer in to investigate the resulting textures and colors.

Currently a professor at Millersville University of Pennsylvania, Sigel began her explorations into Egyptian paste while

at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan,

1

Welded ¼-inch steel rods form the frameworks for the sculptures. The Egyptian

paste is added to the finished framework.

2

3

Pressing thick Egyptian paste into the

voids within the framework. Wear gloves

when working with this caustic material.

4

Refining the forms further using a soft rib to smooth the

Egyptian paste and refine the shape.

Using a soft rib to compress the Egyptian paste and remove excess to reveal

the steel supports.

5

Using a fettling knife to smooth the surface of the Egyptian paste between the metal supports and clean excess paste from the supports.

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

23

process | Push/Pull: The Art of Deborah Sigel | Mary Cloonan

the paste with the hope it would flow and

drip. Instead, when she fired the pieces,

the Egyptian paste held its shape, cracking within the confines of the frame. As

she continued her investigations and exploration, she became more enamored

with the steel frames as a line drawing

combined with the ceramic material and

set upon her creative course. The work

feels simultaneously ancient and modern.

Sigel finds inspiration in the beauty

of nature and rational mathematics, and

the pattern and order found there. The

objects are distillations of plant forms

pared to a stoic geometry and joyful

palette; playful, candy-hued constructs

whose fissures are constrained by blackened steel drawings.

Sigel creates work meant to be displayed on a wall, not just for convenience, but as a carefully orchestrated

maneuver. The wall allows her to manipulate the space and interaction between the objects, and to let the shadows play a part in the composition. It

also emphasizes the patterns created by

the grouping, allowing one to view the

whole while investigating the individual,

implement-like objects.

In many pieces, flowers bloom in a

tight grid across the wall, an arrangement that implies a matching game, or

other game of skill. The grid also imparts a careful taxonomy of a botanist’s

organization, allowing for infinite possible arrays. Six petals radiate from a

central metal circle that also serves as a

way to display the work. Rods are bolted

to the wall, and the central metal ring is

placed on this rod, allowing the flowers

to cast shadows and spin or pivot gently,

a random settling that makes the pattern

slightly askance, softening the grid.

Both the Wisps and Bursts series have

hanging loops, presenting them as an implement for use, offering easy access for

the viewer to imagine its intended purpose. Shadows imply pendulums or forest canopies. In Bursts, symmetrical crystalline forms grow from a central stalk, an

enigmatic implement from another civilization. The Wisps possess a more delicate presence, sinewy stems with alternating buds sprouting along the curves.

24

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

6

Loading the 42-inch tall hanging Wisp

structure into the kiln, supported by hard

bricks and a black steel pipe.

7

After the firing, the metal has serpentine

curves due to the action of the heat and

weight of the pods.

8

Completed Wisp forms, to 39 in. (99 cm) in height, showing a variety of Egyptian paste

colors and the way the steel curves as a result of the firing. Photo: Brian Giniewski.

Building the Forms

Sigel welds the frameworks for her sculptures from ¼-inch steel rod, which can withstand the heat of a low-temperature firing (figure 1). Fabricating her frames in this

way gives her the ability to sculpt with strong, bold lines. She sees the forms as a threedimensional drawing for the Egyptian paste to inhabit.

Once the frame is fabricated and cleaned up, Sigel dons gloves to protect her hands from

the caustic soluble salts and to minimize her exposure to colorants, then packs the forms

completely with Egyptian paste (figure 2). Her recipe consists of glass frit, soluble salts,

nepheline syenite, clay, and a small quantity of sand to help control shrinkage. She has reduced the amount of soluble salts, substituting in nepheline syenite, to combat the scumming on the surface that’s common with Egyptian paste. Occasionally a small amount of

lithium carbonate is added if a slight sheen is desired, so that after the firing, the surface

still looks like it did when freshly modeled. Colorants are added at 6–8% in the form of

9

Four Bursts, to 26 in. (66 cm) in height, in a completed installation. Photo: Brian Giniewski.

Mason stains, or 2% for metallic oxide colorants. Sigel started her

investigations into Egyptian paste with two recipes (see page 26).

As time went on she began to favor Mark Johnson’s Matte Egyptian Paste recipe and made a few modifications including firing

higher and lowering the amount of soluble salts. The new recipe

(see page 26) may not conform to the standard idea of an Egyptian

paste recipe, but the modifications work well for Sigel’s sculptures.

The dry ingredients are mixed with just enough water to create a thick, moldable paste. Sigel then carefully hones the surface,

using the spine of the rod as a guide, meticulously smoothing the

paste with a soft red Mudtools rib (figures 3 and 4) and a fettling

knife (figure 5).

Once the frames are filled and refined, she loads them wet into

the kiln and fires them slowly to cone 05 with the kiln lid or door

propped open for the moisture to escape. This is a counter-intuitive process for anyone accustomed to the usual firing techniques

for Egyptian paste, where it’s dried slowly to allow for the soluble

salts to come to the surface creating the self-glazing layer, but it

works for producing the surfaces Sigel prefers.

Still, she does find it fascinating that the pieces stay together despite being fired wet, “Why don’t they explode? It baffles me!” Perhaps it’s the openness of the paste body, which contains little clay.

Perhaps the cracks form early on in the drying process and allow

the steam to escape in a less destructive manner. The combination

of firing damp with the incompatible coefficients of expansion

between the steel and ceramic materials promotes the cracking

and fissures she is seeking, a randomness within the set pattern.

Note: You can fire wet. Pots explode in a kiln when the outside

dries and traps water inside. As the water turns to steam and expands, it has no way to dissipate, and the resulting pressure causes

the pot to break. When firing wet work, heat the kiln slowly.

Loading the kiln also influences the final work. Flowers are

fired flat on a bed of sand, this supports all the petals while supplying a release in case of over fluxing. Wisps and Bursts are hung

in the kiln, in the same position they will be displayed after the

firing (figure 6). Sigel builds brick towers in the kiln with a support rod made of black steel pipe, the kind used for gas lines, that

the top loop of the steel armature hangs from. An interesting alteration occurs in the kiln. The Bursts, being a single, centralized

point or weight, remain straight. The Wisps start off straight, but

the offset placement of the pods distribute the weight and heat

differently creating serpentine curves (figure 7).

As individual pieces or as a whole installation, there is a quiet

elegance and rhythm to their geometry (figure 8). They’re stoic,

but there’s also a strong sense of humor; playful colors imply

toys and their display cause one to invent games with the quirky

implements (figure 9).

For Sigel, the materials are more than just a curious aesthetic

result; they become a metaphor for the effects of time. It’s about

embracing chance and revelling in the precarious balance of

chaos and order. The kiln is an important partner in her creative

process, it alters with heat and time, transforms the steel and

Egyptian paste, recording history, and endurance. In her work,

Egyptian paste and steel are integral and integrated elements, a

symbiotic relationship creating controlled serendipity.

Deborah Sigel is a full professor at Millersville University of Pennsylvania

in Millersville, Pennsylvania where she teaches ceramics. To see more of

her work, visit http://deborahsigel.com.

Mary Cloonan is an artist, instructor, independent curator, and the exhibitions director at Baltimore Clayworks in Baltimore, Maryland.

If you’d like to try using Egyptian paste but don’t want to mix your own, check

out prepared versions at www.amaco.com and www.lagunaclay.com.—Eds.

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

25

Deborah Sigel’s

Egyptian Paste

(Modified from Mark Johnson’s

Matte Egyptian Paste)

Cone 05

Newly released DVD

of a master artist.

Ferro Frit 3134. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20.60%

Bentonite. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8.25

Sodium Bicarbonate. . . . . . . . . . 0.50

Nepheline Syenite. . . . . . . . . . . . 2.60

Silica . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68.05

100.00%

Mixing: Start with 33% water as each colorant

takes a different amount of water, cobalt carbonate needing a good bit more than the others. Add

more water in smaller increments as the paste can

quickly become over hydrated and sticky. Paste

tends to stiffen up by the next day or two and will

need to be re-wedged to become pliable again.

*Rose Pink Mason Stain is no longer available, and

the green stain that Sigel uses is imported from

Taiwan. Substitutions will require individual testing.

Mark Johnson’s MATTe

EGYPTIAN PASTE

Cone 08

Sodium Bicarbonate. . . . . . . . . . . .

Ferro Frit 3134. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Bentonite. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Silica . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6%

20

8

66

100%

JUANITA’S PASTE

Cone 08–06

Nepheline Syenite. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Soda Ash. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Sodium Bicarbonate. . . . . . . . . . . .

Ball Clay. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Fire Clay. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Silica . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

30%

5

5

10

10

40

100%

Add: Bentonite. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1-2%

Deborah Sigel started her investigations into Egyptian paste using both Mark Johnson’s Matte Egyptian Paste and Juanita’s Paste recipes before modifying Mark Johnson’s Matte Egyptian Paste recipe to

better fit her needs.

26

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

Internationally renowned ceramic artist, Warren MacKenzie, shares his thoughts on

ceramics and the expression of personal and cultural values in an intimate conversation

full of humility and candor. This DVD is a one of a kind view of his work and the artist.

Denver: 5303 East 47th Avenue, Unit N, Denver, CO 80216

Minneapolis: 1101 Stinson Blvd NE, Minneapolis, MN 55413

800.432.2529 612.331.8564 fax www.continentalclay.com

8 DESIGNS

AVAILABLE IN

SOFT & FIRM

ALL SILICONE

RIBS ARE 1/4”THICK FOR

SUPERIOR COMFORT

SEE YOU AT NCECA

BOOTH 229 & 231

SMALL &

MEDIUM

RIBS

$4.95

EACH

LARGE

RIBS

$5.95

EACH

SILICONE

RIBS

626.794.5833

Add: Silica Sand. . . . . . . . . . . . 5–8.00 %

Add: (for sheen)

Lithium Carbonate. . . . . . . . 0.125–.25%

For Cobalt Blue

Add: Cobalt Carbonate. . . . . . . . 2.00%

For Yellow Add:

Degussa/Cerdec Bright Yellow. . . 6–8.00%

For Pink Add:

Mason Stain Rose Pink*. . . . . . 6–8.00%

For Orange Add:

US Pigment

Tangerine Inclusion Stain. . . . . . 6–8.00%

For Green Add:

Imported Green Stain*. . . . . . . 6–8.00 %

For Purple/Lavender Add:

Mason Stain Amethyst . . . . . . . 6–8.00 %

For Black Add:

Mason Stain Chrome Free Black. . 6–8.00%

WEEKEND, ONE-WEEK AND

TWO-WEEK WORKSHOPS

2014 INSTRUCTORS: MOLLY HATCH

DIANA FAYT • KENSUKE YAMADA

HIROE HANAZONO • JOSH DEWEESE

TOM LAUERMAN • LINDSAY OESTERRITTER

LANA WILSON • DAVID SMITH • GEORGE

BOWES • DAVID EICHELBERGER • JEREMY

RANDALL • CURT LACROSS • JULIA

GALLOWAY • KIP O’KRONGLY • MICHAEL

KLINE • EMILY SCHROEDER WILLIS

SANDY BLAIN • AKIRA SATAKE • TIP

TOLAND • STEVEN HILL • NICK JOERLING

JIM & SHIRL PARMENTIER • BRAD

CANTRELL • MELISA CADELL

GATLINBURG, TN

865.436.5860

ARROWMONT.ORG

Spectrum Glazes

Continuing to lead the way.

Cone 5 Semi-Transparents and Celadons

1461

Onyx

1462

Rainy

Day

1463

Cerulean

1464

Moroccan

Blue

1465

Light

Celadon

1466

Celadon

The newest additions to our glaze lineup are twelve mid-range SemiTransparent glazes. These are the perfect complement to detailed ware

and offer a wide-range of color offerings with a focus on the many faces

of Celadons in an electric oxidation environment.

1467

Spring

Green

1468

Bottle

Green

1469

Mimosa

1470

Cranberry

1471

Orchid

1472

Watermelon

SPECTRUM GLAZES INC. ● CONCORD, ONT.

PH: (800) 970-1970 ● FAX: (905) 695-8354 ● www.spectrumglazes.com ● info@spectrumglazes.com

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

27

The Folk School

changes you.

engaging hands and hearts since 1925.

come enjoy making crafts and good

friends on 300 natural, scenic acres

in western north carolina.

John C. Campbell Folk SChool

folkschool.org

BraSSTown

1-800-Folk-Sch

norTh carolina

new

13 fabulous

glazes added to

our line of amazing

cone 6 glazes

16

Doug Casebeer

CERAMIC WORKSHOPS

Summer 2014

Anne Currier

Michael Sherrill

2014 SUMMER FACULTY

Doug Casebeer | David Pinto | Andrew Martin | Sam Chung | Sara Ransford | Anne Currier

Birdie Boone | Debra Fritts | Paul McMullan | Matt Long | Akio Takamori | Sunshine Cobb

John Gill | Andrea Gill | Ralph Scala | Mark Shapiro | JJ Peet | Sandi Pierantozzi

Neil Patterson | Michael Sherrill | Brad Miller | Andrew Hayes

Serving potters since 1975!

Quality Products! Excellent Service! Great Prices!

Visit our web site to see many exciting new products

www.tuckerspottery.com

1-800-304-6185 Richmond Hill, Ontario, Canada L4B 1H6

28

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

Jamaica Field Expedition

April 26 - May 3, 2014

Wood Firing: the art of fire

with David Pinto & Doug Casebeer

and guest artist Christa Assad

For more information, please visit andersonranch.org or call 970.923.3181.

5263 Owl Creek Rd., Snowmass Village, CO 81615 | P.O. Box 5598, Snowmass Village, CO 81615

Oil Bottle and Trivet

Altering in Unison

As potters, we commonly receive a certain wise suggestion in our

early years of making pots that goes something like, “You should

make the pieces that you want to use.” To decipher the advice further, we should make pots that align with our interests, use them

frequently, and in the process learn more about how to finesse

the nuances to improve their design and function.

The oil bottle has been one of these forms in my studio and

kitchen. I love to cook and I love pots and, basically, as soon as

I made my first oil bottles, one found its place on my stove top,

supplying me with olive oil every day. Through getting to know

several oil bottles over the years, the functional details I find crucial in a ewer are a narrow opening in the spout that decants

a slow steady stream of oil and a saucer to catch the inevitable

drips of the viscous liquid. My aesthetic choice of abstracting a

bottle set up an exciting challenge of designing a saucer to fit an

by Marty Fielding

out-of-round shape. The set demonstrated here is an elongated

diamond with a slab-built spout and hollow lid. Think of these

directions as a guide for your own explorations.

Making The Bottle

Start by throwing a bottomless cone that tapers slightly inward

from the bottom to the top. While the cone is still round, plan

where the four corners will be by making small marks on the rim

with a finger or tool. Remove the cone from the wheel head or bat

and place it on a dry, porous board. Now, place the finger pads of

your hands on the adjacent sides of one of the corners. Slightly lift

the cone off of the board for more flexibility and press your hands

toward each other to establish an acute angle. Repeat this action for

the opposite corner. Continue altering the remaining corners to establish a diamond shape. You can sharpen the edges by supporting

Marty Fielding’s oil

bottle and trivet, 4 in.

(10 cm) in width, wheelthrown and altered

earthenware, terra

sigillata, glaze, fired to

cone 03 with renewable

electricity, 2012.

PotteryMaking Illustrated | March/April 2014

29