Trade Networks and Interaction Spheres--A View from

advertisement

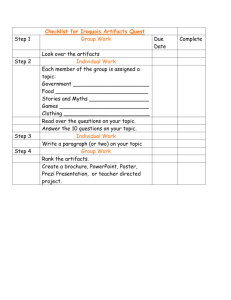

WILLIAM H. ADAMS Trade Networks and Interaction Spheres-A View from Silcott ABSTRACT The people of Silcott, a small farming community in southeastern Washington, participated in six major trade networks: local, local-commercial, area-commercial, regional, national, and international. These networks are examined through the ethnographic, historical, and archaeological data. Remarkably, the regional, national and international networks are best studied through the archaeology, whereas the local networks and the area commercial networks are best examined through the ethnography. These networks bound Silcott into an integrated community. while at the same time they linked Silcott to the national economy via the various networks. From family to community, from community to nation, people are entwined in economic networks eventually linking the individual consumer to the products of the nation. This paper explores the various networks linking Silcott, Washington to the areal, regional, and national economic networks, and examines the various internal networks with Silcott itself. The network consists of a hierarchy of central places towards which people are oriented for social, economic, and political reasons. The “main street” of Silcott was the central place there. The nearby towns of Lewiston and Clarkston were the central places towards which many other small communities like Silcott were oriented. Lewiston and Clarkston were in turn one of many towns oriented to Spokane. Spokane’s interests were directed toward Portland and Seattle. This hierarchy linked the main street of Silcott to the main street of Portland through the networks of other main streets. The interaction sphere is similar to the network except that the individual linkages are in themselves not as important as the fact of their existence. Thus, it will be demon- strated here that Silcott, as part of a national interaction sphere, was linked to such places as Hershey, Pennsylvania even though the individual strands within the network are not known. What is important is that Hershey and Silcott interacted, albeit indirectly. Silcott people bought Hershey’s Cocoa, thus stimulating Hershey to produce more cocoa in order to provide Silcott with more cups of hot chocolate, and so on. Though this may seem trivial, it is not. This was just one link which Silcott shared with other communities; there were many others. When all these links are considered we see the tremendous quantity of shared links which provided the economic and social fabric of the nation. By studying one group of consumers, those in Silcott, we see how successful the nation was. Silcott is a small farming community in southeastern Washington (Figure 1). Located on the narrow floodplain of the Snake River and in the steep tributary canyons, the patchwork of farms emphasized irrigated orchards and gardens in the valleys, wheat and grazing on the hillsides. The settlement began in the early 1860’s and continues to the present. The ethnographic and archaeological study of the community concentrated on the 1900 to 1930 period. That research has been dealt with elsewhere (Adams 1973, 1975, 1976; Adams, Gaw, and Leonhardy 1975; Gaw 1975; Leonhardy and Day-Ames 1975; DayAmes n.d.; Riordan 1976, n.d.). FIGURE 1 . Location of Silcott, Washington. 100 The manufacturers of an artifact found in Silcott were identified wherever possible. The manufacturers (and their products) are presented in Table 1, along with their distance from Silcott, their location, and the frequency with which their products were found in Silcott. We wrote to extant companies, seeking information on the product and its history. The replies varied, but most were useful for identifying, dating, and locating the origin of the product. Many products were embossed or imprinted with both the name of the manufacturer and its location, thus simplifying some of our work. The locations of these companies are shown in Figure 2. Two factors skew the sample. First are the large but unknown numbers of home-made artifacts, either unrecognized or not present in the archzological inventory, but indicated by the ethnography. Second, those artifacts which show the brand name (and hence can be identified) are often intended for the national market. Local brands are only rarely marked. These problems will require consideration in the interpretation of these data. FIGURE 2. Locations and numbers of companies for products found in Silcott The linear miles from Silcott to the place artifacts one exception to this is made: it is of manufacture were plotted. These relative assumed the European products entered the distance figures approximate the real distance United States via New York City, while the the artifact travelled, though in all cases dis- Asian products entered via Portland or tance would have been more than the figure Seattle. Linear measurement was made in a given because of dog-legs in the routing. It is dog-leg fashion from the foreign port to the axiomatic that the shortest route is generally entry port to Silcott. The American companies the most economic one. For comparative and products were placed into five distance purposes here it is assumed the items travelled groups according to the kind of product directly to Silcott in a straight line. For foreign (Tables 2, 3 ) . 101 TRADE NETWORKS AND INTERACTION SPHERES-A VIEW FROM SILCOTT TABLE 1 LOCATION OF MANUFACTURERS OlStance Location Manufacturer source source category PlrodUCt R71 821 E41A "01c y051 270 270 1 Renton W R S e a t t l e w* 1 1 1 1 280 Portland 3 R H 4. " I- 4, E, G & 603 640 680 Sacramento C i i Stockton cI\ bar Franciiin CA r a n n 1 n q Jar 01,ve olll Uelro-Kola, Purola Beer B e e r . Liquor E x p r t Beer Coffee I, H 1 1 1 mrve 311 .mra MJstard Jar Mustard Jar Beer M f t l f Beer M t t l E 4 2 4 ilrclr1e , m a /I 1 22 1 2 4 1 Whiskey H.H.H. 8 0 1 5 8 Medicine F H 17 1 r41u 0130 0131 116Y n03x COI d20r E04 E33W E33Y e41m 1140 N138 D07D A601 D2UR A491 1.52 E?]", Y E335 A080 E4lL R6bC H // H 7. i E E )?' 1 Ketchup Bottle Medicine Bottle Whiskey Beer 1 6 1 I P~ckles" Extract 4 22 slllce 3ranqe Extrait Rivet :m'T I Rust $ e m 117w E33N h66E F41E r60 025 1161, M D30R N07G NOlV 5 002 5 U56 85 c01 1 E411 5 1 E15 &?OR 605C 13 I 5 2 24 008 E 0 9 6038 DO6 051 DllA d02r 823A D07P d13t A66K E4IF. G R 7 0 A . .'E B e e r Bottle C a n r i n g Jar 69 E413 1 7 5 E33 E14 8 c09 eeer 17 5 2 38 A73 15 1 151') 11760 a46H 0 1 4 02% s t r e a r o r 11 Y Elm. E American B o t t l e carpany 1520 1530 1540 H i l l s b o r a I: Bellevillr TL C h i s a q o TL H I, A n A schram ~ u t o m a t l cs e a l e r compin.; 'idolphus 3usck :lass M f q . :owany P e p s o d e n t Compani P d e l b e r t M. ? o s f e r and omrany Armur's brnwur's A. Sa".ford Sanforc 4artford \, B B H 4 A R A mttie Toothpaste Medlclnr Bottle Top hotc', Brand C"ld cream Llbrary Paste '7) Ink E E E E 4 seer Bottle 6 * ,, R, H 8. C A Beer B o t t l e Yedicine Bottlea Wine of Beef and Irona nrntment saw s?.rpe"er x(lnera1 water O v e l m Cream F A. R h '0-qh Cyrup Laxatlre lhiiksy 821 105 G02D 7 4 5 Ink Mustard Pickles Medicine Velvet Tobacco Dr. Price's Baking Powder 2 B 1166H Bll" 3 10 34 1 a18 A59 D42 A26A R50 B D I 802 B O 3 d091 102E 0075 11611 1188 8 A70N a 6 6 F R701 E 3 1 5 E06 E06 NllB 101a R72 1191 D07P OD'lR E24F Distance 1700 1750 1750 1790 182s 1850 1850 Locatlo" F l l n f HN Detroit HN T o l e d o OH K i n g s M i l l OH CDhUMUS OH Newark mi Cleveland OH source R Finck F o r d Motor Company Prni-cular Chemical Compan) R A HLE Co. I B H Peters C a r t r i d g e Co. Dr. SBH & Company Amerlcan Bottle Company R R * Ashland OH East LIV~TDOO OH~ 1900 New Orleans LA 1940 Whee1mg 1925 Beaver Fa115 PA 1960 * MuSteTOle company NFG CO. Dlll V a l v e s t e m F . E . nyers & 8110. T a y l o r , S m l t h , and Taylor Honer L a u q h l i n Marker Pottery Company Knaules. T a y l o r and X n w l e s . . . A L.E. H FI~CCW P i t t s b u r g h PP H B 2120 2200 Hershey FA P h i l a d e l p h i a Pa C A J6E Mdyer P o t t e r y Company J6E m y e r p o t t e r y company RLDH Chambers DT. J. H o l t e t t e l Hershey C h o c o l a t e Company Henry K. Warnpole a n d Company 1940 1950 2010 W e S t f l e l d NY B u f f a l o NY R o c h e s t e r NY c 2040 2090 2150 2160 2220 2250 2250 w Welch Grape J U l C e Company Mentholatum Company F . E . Reed Glass Company I\ ??? Corninq Glass Works Blnghanpton NY U t l c a NY Illon Gorge NY D r . Kilmr a n d Campapy savage RImS company Remngron * I n s company B r o o k l y n NY New York NY R * E E E E c 2250 New 'forkb NY A * F ii A R A h A 2210 2230 2230 n. c The BayeI Company 6 c h r a d c r V a l v e Company Best Foods U n i t e d S t a t e Tobacco Company 3-in-One 011 Company The C e n t a u r Company P h i l l i p s H l l k o f Maqnesia C h e s e b r a u q h Hfg. Co. E . R . Durke and Company N a t l o n a l Remedy Company ~ a r r e r rand Company . .t and Co. . .gists Colgare Colgate E . Weck auto S t i o p S a f e t y Razor Company . Spark Plug Overall Vibrator ~ o i n t Penslar Panatells cigar lmunltran Peruna Medlcrne B o t t l e a Musterole ,? EliR C33 R 4 A 2 1 56 2 1 9 I H cocoa L i q i i d Wheat Grape I l l c e Wentholarum Medicine Bottle Whiskey Pyrex c BOW1 P Rmunrtlon R A5"lrl" 2 a Tire V a l v e 4 A 1 1 4 1 1 A, E nayonnalse? Copenhaqen A. n 011 I r l e r c ? e r ' s castorra Medlcine "aSell"e Salad m e s s i n g En-Ar-Co 0 1 1 " l r q l n l a Dare Medlclne Toothpowder R 01ntment D, E li. c R A n R R n S t l f f e n l n g clamp n " a l a Razor Canning 2330 L o w e l l HA E A R C a n b r l d g e MA Boston MA C A * A 1 R U n i t e d States C a r t r r d g e Company C.1. Hood a n d Company i i y e r company Carter's I n k Company Hlrmny nhltrenare Hood Rubber Co. George Frost Company U . S . Fastener Company 5500 Japan I\ ??? 71' 6050 Tunsfall ENG R A l f r e d Meakin Hanley ENG R Johnson Brothers John Haddock 6 Sons Yedqwood and Company J o h n Edwards and Company J. b G. Meakin C h a r l e s Heakln Charles l e a k i n Edward C l a r k e Edward C l a r k e N u t f a l l b Co. B a l l Brothers ~ a v e y6 Moore, LTO A Jars 1 1 11 4 1 23 1 I 1 2 2 5030 5348 A02 6031 013G E438 H07R 053 N170 N156 I l 8 Q N12C W l R B Nl8H 117he 1165 R25 1 5 5 D07Q GOhA a12 NllO h30 d070 A35 0308 0071 1171 NllC N148 L04B LOlP 2 1 1 1 Prince Rlbert 86 R BrORa-Seltler 4 R Edgeworth R.J. Reynolds Company R I I 9 SWamii-Root *""nitlo" Bakrnq Powder? GlaStOnbUrg CN Waterbury CN B r i d g e p o r t CN 80 9 1 R A. .us a n d B r o . Company n18n SOOG 5OOC 500s SOCJ 5271 1 A. W i n c h e s t e r Repeating A r m Company The TE V l l l l a m Company I n t e r n a t r o n a l SllYer conpany union ~ e r a l l i cC a r t r i d g e Co.qany N14Q Steer's Head Canning Jar R A 1 H Rumfard Chermcal Works New Haven CN n181 3 E R i C h m n d VI\ 6038 Nl2I 1 1 a w l . saucer B o r a t e d Talcum Charm Candy 2280 2290 2290 2290 132 E03 2 COlUmba Peptic Bitters A 2200 i16k N 1 5 N16 N l i A R 1 A. C Emerson Drug Company N03F 7 2 2 n n I 56 1 Gaynor Glass Works G e r h a r d Hennen Chemical Company C h a r m ' s Candy Company B a l t r m r e MD 1 9 32 Cer*ml' P l a t e . ceramc C 2150 NIB* d03 Ceramic A Providence RI 1 2 A H WmsLon-Salem NC NlBD N18Q a. Salem NJ 2330 category 2 3 rz R A . Number Valve stem Lever Newark NJ B l o o m f i e l d NJ 1060 2350 2350 ii Bras Corning NY Hudmn NY A, C Junq C H Product 5ource AC S p a r k P l u g Company A li 1850 1900 Ma"YfaCf"reI c 3 620 102F g01 1026 A A 58 N15 N16 N l l 1 E 3 35 N22E M02 N 1 5 N16 N i 7 A * 4 N l b N17 G F IO C R A. C R 1 1 3 3 E 2 Y O 9 A Y09E N04L NOlR A 1 N"7H 1 POlA 2 p0411 6 SOOE A. A, 1 052C D52H 1268 R41R 045 som, n S17AS19RS7i.a Burslen ENG Tunstall ENG A F e n t o n ENG A R Hanley ENG A BurSlem ENG A ii T u n S t a l l ENG St. H e l e n r ENG S h e f f l e l d ENG H l d d l e s e x ENG 6650 7050 Brenen GER ??? GER Bavaria GER Silesia POL R H A H A A 2 1 A 1 I I I R I li A R 55411 sim 5861 1 GlOC Lioa a666 H 1 GlOA 1 A A. 517d S09A S O I A H H A. 2 1 1 1 2 SOSF SOIA A H e m n n Heye G l a s f a b r i k Orla I?) 1 p031 R ??? I A ??? 2 POOR PO51 P39A i?? 1 p1711 A. H I A. r? 103 TRADE NETWORKS AND INTERACTION SPHERES-A VIEW FROM SILCOTT NOTE: The following indicate the sources of identification of location and manufacturer embossed/ imprinted/raised letters indicating place, company paper label data from company Periodical Publishers' Association of America (1934) Brand Names Foundation (1 947) White (1974) Newspapers, city directories Toulouse (1 971 ) Colcleaser (1 967) a Listed twice: by bottle maker and by bottle filler. bProduct marked New York; ambiguous as to city or state. TABLE 2 NUMBER OF AMERICAN COMPANIES BY DISTANCE Company a 0-500 5001000 10001500 15002000 20002500 Total 7 1 14 18 19 13 35 42 a Condiment . . . . . . . . . Liquor . . . . . . . . . . . . . Medicine . . . . . . . . . . . Other. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4 5 2 4 3 2 1 2 0 0 3 1 5 5 15 17 TOTAL . . . . . . . . . . 15 8 4 42 40 PERCENTAGE . . . . 13.76 7.34 3.67 38.53 36.70 109 100.00 Includes extracts, spices, baking powder, etc. TABLE 3 NUMBERS OF ARTIFACTS BY DISTANCE 5001000 10001500 15002000 20002500 Total 0-500 a Condiment . . . . . . . . Liquor . . . . . . . . . . . . Medicine . . . . . . . . . . . Other. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7 7 24 21 41 12 8 8 0 0 23 85 171 129 142 68 32 1 46 218 25 1 149 243 400 TOTAL . . . . . . . . . . 59 69 108 5 10 297 1043 Artifact PERCENTAGE . . . . a 5.66 6.62 Includes extracts, spices, baking powder, etc. 10.35 48.90 28.47 100.00 104 Silcott participated in six different trade networks or interaction spheres. Some of these can be documented archaeologically, for example the regional and national networks, whereas the others can be approached only through ethnography. These six trade networks were: (1) local; (2) local-commercial; (3) area-commercial; (4) regional; (5) national; and (6) intemational. The local network of Silcott was a barter system called “neighboring”. It is familiar to anthropologists as the dyadic and polyadic contract. Neighboring was a social contract between two individuals or two families in which tasks too large for individuals were tackled collectively. Neighboring was a phenomenon of frontier America and of a generally cashless economy. By sharing work as harvest, barn building, and slaughtering, a greater mutual wealth could be achieved. The economic function of such ties created social relationships. These invariably led to greater social cohesiveness. Distribution of social and economic ties was usually horizontal and single-stranded, that is, relationships developed among peers and the activities were generally task specific. Neighboring can be many-stranded, a complex relationship based along several different lines. For example, two families help each other at harvest, at slaughtering, and at general gettogethers. Horace Miner made a study of a farming community in Iowa where he found that “a farmer may ‘neighbor’ with some family a mile down the road and ignore the farmer next to him . . . simply because he follows the dictates of personal preferences and congeniality’’ (Miner 1949:37). This held true in Silcott as well (Day-Ames 1975). One might neighbor with a half-dozen families at various times during the year, each of whom in turn neighbored with a slightly different set of families. The multitude of single-stranded and many-stranded relationships wove a network of social alliances binding Silcott into a single integrated community. On the geographcal fringes of Silcott relationships were woven with families whose social and economic ties were primarily oriented elsewhere. In the upper reaches of Alpowa Creek, along Knotgrass Ridge, people who were oriented towards either Peola or Silcott usually neighbored with closer people. If you interacted more with Silcott people you identified with Silcott-you might live nearer to Peola but consider yourself to be “from” Silcott, whereas your neighbor a mile further towards Silcott might be “from” Peola. The distinction was made on the basis of neighboring. The boundary of the community was not a straight line on a map but instead a zig-zag patchwork of farmsteads. Economic ties of neighboring created social ties, which in tum created social boundaries and resulted in economic boundaries-a swing full circle. Neighboring may be regarded from two aspects: practical and economic. From a practical standpoint it makes sense; some things cannot be done efficiently with a small number of people. Examples include major construction projects such as road building or barn building. With cooperation the work can be done. Similarly, but for different reasons, was the slaughtering of livestock. By alternating the slaughtering between several families, fresh meat was available more frequently without the need for either greater consumption or preservation. This is also a form of insurance. Giving away meat when you have it causes an indebtedness which can be claimed at a later time when you do not have any meat. The more persons indebted to you, the greater your security if some calamity descends upon your farm. Indeed, “many superficially odd village practices make sense as disguised forms of insurance” (Lipton 1968: 341). In later years farmers brought their own hogs and shared only the labor, not the meat. The economic factor of neighboring is an important one, for in a society such as Silcott where there was little cash, labor was traded, not bought. Up until about 1910 labor was often traded on par, that is, you worked a day for someone and later he worked a day for you. No consideration of wage rates was TRADE NETWORKS AND INTERACTION SPHERES-A VIEW FROM SILCOTT 105 made. This resulted in capital gains without construct what these stores were like has been the expenditure of hard-to-come-by cash. difficult because people remembered the Once a cash equivalence for work was mea- stores from different time periods and the sured, the reciprocal relationship was under- stores were changing throughout the time mined. When work could be expressed in of occupation. The country general store was the focal dollars, people were more reluctant “to be so beholden” to someone else. Wage labor was point for the entire community, but after essentially limited to work in the big company about 1890 general stores began to decline (Carson 1965:279-280). The reason for this orchard or the grain warehouse. Neighboring, as a socio-economic entity, decline was a shift in orientation, socially binds families and binds the community. and economically. Mail order houses such as Sears Roebuck It is a local network for the distribution of wealth in the form of goods and labor. Neigh- Company and Montgomery Ward Company boring results in informal bartering disguised took an increasing amount of the country as gift giving and helping-visit a neighbor store profit. This was particularly galling beand bring some garden produce, help him cause the storekeeper was usually the postbuild his barn. This relationship lasts, however, master as well. Even though Sears would only if it is reciprocal. Reciprocity, whether sell merchandise in plain brown boxes, the it is formal or informal, must occur if neigh- storekeeper/postmaster usually knew the boring is to be continued, if the dyadic social source. But there was not much to be done about it. Mail order houses offered much contract is to be fulfilled. Probably the only area where archieology lower prices and greater variety than the can study this local network of neighboring country store could. Of course, the storekeeper is in the sharing of slaughtered livestock. It is did have some advantages-he could offer quite likely that certain families would ex- credit, something which the mail order places change a given unit of meat each time, say could not do until C.O.D. came into being. a quarter or side of beef, and that some pref- Mail orders were also subject to long delay, erence might be formed regarding the side damage in transit, freight charges, and often of the animal exchanged. This behavior would cheap merchandise. The storekeeper had the largely be idiosyncratic, yet it might well be advantage of having the merchandise where predictable. For example, each time Farmer it could be examined. The biggest problem A butchers a hog he gives the right front the storekeeper faced was competing with quarter to Farmer B. Farmer B returns the the tremendous variety to be found in mail next time with a left front quarter for Farmer order catalogs. The country store could only A. This kind of disparity should be revealed stock a small quantity and variety of merin the frequencies of the various bones in chandise. the archaeological site. For the sites excavated The customers of the old general store did not in Silcott, there is not, however, any kind of expect to find each article at various grades and indication of this in the rather small faunal prices. The volume of business would not support more than one kind of axe, one kind of assemblage. The hypothesis is not negated; rake, one quality of boot (Carson 1965:70). we are simply not in a position to test it. For some of the prehistoric sites in The Alpowa, The problem of variety was the reason for Richard Lee Lyman (1976) has been able to another competitor: the city store. Until the document differential sharing on the basis advent of a good system of roads, the country of faunal remains recovered. dealer had little competition from city stores: The local-commercial network in Silcott Trading areas were established by the distance consisted of the interaction between the cusa farm family could travel by horse back, oxcart, tomers and the two general stores. Trying to or wagon. A circle with a five-mile radius would 106 represent a fair estimate of the amount of geotake graPhY in which a a serious commercial interest (Carson 1965:23). Because Silcott was so sparsely settled, the distance the which customers were to was greater-fifteen to twenty Interestingly enough, former residents that five was a pretty long ride to visit someone. Even as late as the 1920’s, using automobiles, “the farm On the average six to eight for hardware, fourteen for furniture, and twenty for women’s fashions” 1965:290)’ The advent Of good roads after War I brought new business t’ the and it took business away as well; but it always than it brought in. took more business Cliff Wilson built his general store about 1905; five years later, in 1910, his half-brother, Bill Wilson, built a general store two hundred yards to the north of CWs. Until about 1914 or so both stores competed with general merchandise but there was hardly enough business for one store much less both. Cliff was also the postmaster so he had an additional Source of income. Bill Wilson expanded his operations to include a saloon and dance hall and gradually (though never completely) phased out his general merchandise line. Both places rented out rooms for the night, though properly speaking they were only beds. Cliff also diversified by putting in gasoline pumps after World War I, a sign of impending doom for Silcott appearing under the .guise of progress. Both for a new road stores eventually became only convenience along the south side of the river to Clarkston. stores. ‘<Theold country trader found himself The road would eliminate the two ferry trips between wind and water, left with a shrinking Or the Overland trip which was then business of low-profit necessities, the sugar, It the need for the salt, and the flour, and convenience goods local general stores and such as a pocket tin of smoking tobacco, a eliminate many of the social ties binding the deck of Camels, cola drinks, and the overalls community together. It would make it possible that did not get on the shopping list when the for people to go to town and family last visited the city” (Carson 1965:286). The ferry trip was so expensive that “farmers Judging from informants, descriptions of from southern Asotin County frequently cl. iffs from the early 1920’s until his death in in made a three-day journey to Pomeroy’ beto market lieving it to go the long than to pay high ferry fees to nearby Lewiston” (Anon. 1955:9). Facility of transportation was the single greatest factor in the dynamics of trading networks. Distance was less of a factor than topography because the steep canyons restricted and constricted travel. Initially, the automobile did not necessarily make the trip easier. It did make it faster, but the automobile required good roads. However, the trip to town did, eventually, become easier: What the railroad did to the buffalo, the automobile did to the country merchandiser. Going to town meant riding to the nearest big community, twenty to forty miles away, where there were full stocks of goods in all lines, better prices for eggs and chickens, as well as movies, barbers, dentists, lawyers, beauty shops, service stations-not just one facility, but a]] the conveniences of urban life (Carson 1965:281). 1937 and the closing of the store, very few sales were made. Cliff and Mollie Wilson had very few needs and desires, They could get by on next to nothing: food, and kerosene for the lamp, were about all they needed. The store was a shamble, the candy wormy, the food in boxes either long since eaten by mice, or rotten. One passerby stopped for gas and also bought a box of crackers not opened for several milesone mouse, no crackers. Cliffs role in the community was reinforced by his role as postmaster. But even in its heyday people tried to avoid purchasing major items at his general store because they were shopworn and high-priced. Nevertheless, at least in its first two decades, it was an important social and economic focal point for the community. During the evening when Cliff “disturbed” the mail, people would gather around and gossip, and in the mid-1920’s TRADE NETWORKS AND INTERACTION SPHERES-A VIEW FROM SILCOTT listen to his radio. Both Cliff and Bill figure greatly in local folklore, as culture hero and anti-hero. They both fit the model of a storekeeper as described by Gerald Carson (1965). Both sold goods which were not what they were actually supposed to be. For example, no matter what kind of motor oil you wanted, Cliff kept it in stock. Of course, it all came out of the one and only oil barrel. But in truth it was that oil, for he would add a little of the proper brands to keep from lying about it. Bill Wilson’s was more of a convenience store after its first few years. His saloon and ice cream emporium provided income to supplement his gambling winnings. Bill’s Place was a male bastion. Women just did not go there much, because of the liquor, gambling, and perhaps even worse, dancing. One woman lived some thirty yards away but was never inside the store. She preferred to bypass it for Cliffs. Bill oriented much of his business towards the harvest workers in the orchards and grain fields. He supplied them with food and clothing as well as with an entertainment center. Both stores offered credit, but very judiciously. Informants stated that neither place offered credit, but continued to state that both “carried” certain people, especially just before harvest. Most likely their official policy was one of no credit, but those persons they were really familiar with could get credit. Because offering credit is risky, the store owner must either limit credit or limit business. Barbara Ward wrote about two general stores in a small Chinese fishing village which did not seemingly have enough business for two stores. The reason was the credit system: each storekeeper could know the personal finances of only about half of the village well enough to extend credit. This imposed a limit on the amount of business each storekeeper could safely maintain (Ward 1967:138). There is not enough evidence on the internal dynamics of Silcott to know if this was also a factor there. We know that they gave credit, but we do not know the limitations of it. Another system for which there is only a 107 little evidence from Silcott is that of differential pricing. Country storekeepers marked their stock with a code system so they could offer a graduated price scale. This permitted them to fleece the wealthy passerby and give bargains to good customers and friends without blatantly advertising such to customers standing nearby. Several coding systems were used, some of the more popular ones are given by Carson (1965:92). It is likely that both Bill and Cliff used coding systems, but there is no evidence. We do know that they gave a better price or a greater measure to certain people, probably favored customers. Said one informant, “Bill gave more candy for the penny”. The lowering of the price paid for special customers or similarly the giving of greater quantities for the same price insured that customers continued business. The merchant gives up a little profit for increased security. Of course, this is done only if there is competition from other merchants. In a monopoly it would be unnecessary. Sidney Mintz’s study of i, marketplace in Haiti gives us some insight into the relationship of preferential treatment (Mintz 1967). The special treatment given to certain customers he called pratik. Pratik strengthens the buyer-seller relationship and has a number of advantages: the trade is more predictable since the seller knows a certain part of the stock will be purchased; and the buyer knows the merchandise will be available at a good price. In open competition the merchant might receive more money but this would increase competition and substantially decrease security. Furthermore, in hard times without the pratik relationship the seller would have less reliable income and the buyer no reliable source to obtain materials from. In other words, pratik is a means of increasing security by decreasing competition. While a system like pratik can be offered as an explanation of how and why competition between the two Wilsons’ stores was possible it is probably not the explanation. Preferential pricing and giving better measure has been documented for American general stores by 108 Carson (1965) and has been inferred for Silcott from informants’ comments. Archaologically we cannot say which items were purchased at a particular place. For example, we cannot tell if a medicine bottle found at Weiss Ranch Dump came from either of Silcott’s two stores. The reason for this is that there were too many places available for items to be purchased. Thus, we cannot examine internal versus external economic factors through archxology. We cannot say that a certain percentage of the material recovered was originally purchased in Bill Wilson’s Store, a certain percentage from Cliff Wilson’s and a certain percentage from Lewiston merchants. We cannot approach it through written records or the ethnography, either. Area merchants no doubt did a considerable business with people in Silcott. Merchants up the Snake River in Lewiston and Clarkston probably got most of the business, but merchants in the county seat, Asotin, surely received some trade. Occasional trips were made to Colton and Uniontown to sell produce, but that necessitated crossing the Snake and travelling about 15 miles up the meandering Steptoe Canyon to the uplands on the north side. Infrequent trips to Wawawai by buggy, train, or boat resulted in very little cash flow except, perhaps, in wagers when the Silcott Reds baseball team played Wawawai. For the people living higher up The Alpowa the economic orientation was directed somewhat towards the settlement of Peola, but when real purchases would be made they would probably go either to Pataha City or Pomeroy. Since about a third of the area covered by the Silcott community lies in Garfield county much of those people’s business took them to Pomeroy, the Garfield County seat, some twenty to thirty miles away. The people in the higher elevations of The Alpowa went to Pomeroy much more frequently than to Clarkston or Lewiston. Only five artifacts were recovered in Silcott that were demonstrably from area merchants: three beer bottles from the Lewiston Bottling Works and two medicine bottles from the Lewiston Owl Drug Store, but even these were made in the Midwest for those Lewiston merchants. One must bear in mind in the following sections that most items eventually reached Silcott by way of the merchants in Lewiston and Clarkston. In terms of the archaeological evidence, we are on firmest ground when we deal with the regional and national networks from which Silcott ultimately derived its consumer goods. Just how did those networks appear from the perspective of the consumen in Silcott? Based upon the archaeological evidence, the Northwest region produced little of the merchandise consumed in Silcott. Only the four primary nodes in the areal network are represented: San Francisco, Portland, Seattle, and Spokane. Spokane seems to be represented rather poorly considering its distance (100 linear miles) and ex-officio status as “capital” of the Inland Empire. Spokane was linked to the East via railroad on September 8, 1883 but it was not until September 9, 1898 that the Northem Pacific Railway reached Lewiston from Spokane (Meinig 1968:370; Anon. 19555). The Camas Prairie Railroad, built along the north side of the Snake River between Lewiston and Riparia, was finished in 1909 and completed Lewiston’s link to the Northwest rail network (Meinig 1968:383). Although railroads certainly facilitated the flow of goods into, and the flow of produce out of the region, the importance of water transport cannot be ignored. Steamboats ran the Lower Snake River between its confluence with the Columbia River and Lewiston from 1861 until 1940. Because this eventually linked Lewiston (and hence Silcott) to Portland, Oregon, we should expect that economic orientation prior to 1898 should have been directed towards Portland much more than Spokane and Seattle. In other words, the primary node for Silcott would have been Portland until 1898, but after that date Spokane increasingly replaced Portland’s dominance. Seattle was probably less important than Spokane in terms of trade dynamics in the interior until the turn of the century. Certainly it was sub- TRADE NETWORKS AND INTERACTION SPHERES-A VIEW FROM SILCOTT ordinate to Portland. Seattle’s base as a primary node was a result of trade with Alaska and the Orient, not with the interior of Washington. Very few artifacts were identified as coming from the Pacific Northwest (Table 1). This is somewhat surprising-intuitively it seems there should be much more. The majority of artifacts from the four Northwest cities (Spokane, Seattle, Portland, San Francisco) generally are limited to extracts and spices, liquor, medicine, and work clothing. The place of manufacture for most artifacts was not determined; many artifacts could have come from the Northwest but since they were unmarked it could not be substantiated. The archaeological information from Silcott provides valuable insight into purchase patterns. With Silcott we find goods produced in the East were not only economical to ship to Silcott but were also in demand there. Silcott was obviously tied in with the national economy via a complex distribution network. Although the degree of their interaction is difficult to measure, it must have been great. The distribution map (Figure 2 ) shows the known location of each company which produced the artifacts found in Silcott, at the time they manufactured those artifacts. Each symbol reflects the number of each kind of company. The companies are concentrated in a broad belt reaching from the Midwest eastward through southern New England. This concentration was, of course, the major American industrial center of the early twentieth century. This is not in itself surprising. Indeed, it should be expected. But, it is encouraging to see reality actually reflected in the archaeological record. What is surprising are the numbers of products which eventually reached Silcott. Of the numbers of American products recovered in Silcott, a total of 1043 artifacts were identified to their place of manufacture. This represents 15.3% of the artifacts (other than nails) found in the excavations. This appears to be a sufficiently large enough sample to provide a view of Silcott’s participation in the national network. Tables 2 and 3 show 109 that 78.9% of the companies (which produced 87.8% of the products) were located at a distance exceeding 1000 miles from Silcott, and 75.2% of the companies (representing 77.4% of the products) were located at a distance exceeding 1500 miles. Clearly the majority of the identified products in Silcott originated at a long-range distance from there (Figure 3). These data suggest that the economic hypothesis put forth by Klein (1973) is probably not applicable outside of the major industrial region in the Northeast. The evidence from Silcott shows that it was very much a part of the national distribution network. However, we really do not know all the links in that network. While straight line distance gives a useful measurement for comparison, it does not indicate the actual distance a product travelled. Material from the East Coast may have come to Portland by steamer, then to Lewiston by the Columbia-Snake waterway, or by rail. Products could also come from the east by rail but the evidence is nonexistent. The material from the Midwest likely came over the Northern Pacific Railway. The consumers in Silcott were no doubt affected by the transcontinental rad system, and later by the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914. Without comparative data from elsewhere in the Northwest, the relative impact of these events cannot be determined archaeologically, nor can the data from Silcott be seen in proper perspective. We can surmise that most material came by rail, but the exact route cannot be known. The routing through jobber and wholesaler, the hauling patterns, the warehousing, will all remain unknown. All we can say is that the system was successful in transporting the artifacts from production in the East to ultimate consumption in Silcott. Mail order houses probably accounted for many of the cash purchases in Silcott. They likely would have done even more business except for their cash only policy. Cash was a rare commodity in Silcott. Until the 1910’s there was little cash in Silcott, but as commercial orchards developed and provided 110 jobs, and as homesteads were sold to the sheep company, the barter economy changed into a cash economy. Until that time people were in the lengthy process of acquiring enough land to survive on, for it took lots of land in most of Silcott to be successful-Silcott was nicknamed “Starvation Flat”, and for good reason. With cash they were able to increase their purchases from mail order houses such as Sears Roebuck and Montgomery Ward. While we know mail order was important, there is no way to discover just how important it actually was. The only definite mail order artifacts recovered were a liquor bottle embossed with the name of a Portland mail order house, and portions of three Sears catalogs. Although many other artifacts undoubtedly were mail order these could not be identified because most kinds of items available from mail order could be found in area stores as well. It is not known where the coffee in a tin can in a Portland factory was grown. The tea came from Ceylon and the ginger from Africa. Companies Products SO 0 0 0 0 0 s g s s s I O I D 0 ‘ U ( Y I 0 0 I 0 0 l P ! : I 0 0 FIGURE 3. Percentages of companies and products by distance. Silcott participated as ultimate consumer in a trade network which stretched around the entire world. From an archzological standpoint we can never really investigate the complex international networks because so much of the imported goods were raw materials. The few dozen artifacts known to have been imported to Silcott grossly under-represent the actual figures for consumption of materials derived from foreign sources. Many of the identified ceramic vessels recovered in Silcott were made in England, although some were made in Germany, Poland, and Japan (Table 1). Three ale bottles were made in England, while one was made in Germany. The only other foreign artifact identified was an English sheep shears. Summary The people of Silcott particpated in a hierarchy of economic and social networks linking them eventually to the rest of the United States and the rest of the world. Each level of this network hierarchy affected Silcott differently and each level intermeshed with every other level. The “neighboring” in Silcott made possible a surplus of cash which could be used to purchase items at the local stores or the city stores. That cash eventually flowed outward from Silcott stimulating the economy of the region and the nation. The national and regional economy produced and distributed the manufactured items which eventually flowed inward to Silcott. This pendulum of commerce swung from all the other farming communities of the nation to the manufacturers and back to the communities creating a rhythm, a metronome for the nation. What happened in Silcott did affect the nation, because Silcott was linked through the social and economic networks to all the other small farming communities. For the same reason, the flood or fire which destroyed some New England mill town ultimately had an effect upon Silcott. This paper outlined the expanding interaction spheres in which Silcott participated and the networks which bound those spheres TRADE NETWORKS AND INTERACTION SPHERES-A VIEW FROM SILCOTT 111 together. While considered separately here, retailers. Silcutt provided grain for the sourthey are in fact so woven as t o be, in reality, dough bread in San Francisco, apples for inseparable. The imported products found Denver, and the wool for Pendleton shirts. their way through the national, regional, local, and neighborhood networks. English shears cut the wool in Silcott; Brazilian coffee was ACKNOWLEDGMENTS sipped from Silesian cups, while Cuban sugar This paper is a slightly modified version of a chapter was stirred into the coffee by a spoon made in from my dissertation (Adams 1976). I would like Connecticut, and the cup set upon a cotton to thank my committee members for their comcloth made in India covering a table made in ments and criticisms: Frank C. Leonhardy, Robert Ackerman, Roderick Sprague, James Goss, and Indiana bought from Sears. In the return, Mary Elizabeth Shutler. I am also indebted to Silcott grain, fruit, and wool flowed outward Kjerstie Nelson and Eric Blinman for their assisfrom the farmers to the middlemen to the tance in manuscript preparation. REFERENCES ADAMS,WILLIAMH. 1973 An ethnoarchreological study of a rural American community: Silcott, Washington, 1900-1930. Ethnohistory, Vol. 20, pp. 335-346. 1975 Archreology of the Recent Past: Silcott, Washington, 1900-1930. Northwest Anthropological Research Notes, Vol. 9, pp. 156-165. 1976 Silcott, Washington: ethnoarchreology of a rural American community. Doctoral dissertation, Washington State University. University Microfilms, Ann Arbor. ADAMS,WILLIAMH., LINDAP. GAW,AND FRANKC. LEONHARDY 1975 Archaeological excavations at Silcott, Washington: the data inventory. Reports of Investigations, No. 53. Laboratory of Anthropology, Washington State University, Pullman. ANONYMOUS 1955 Jawbone Flat to Clarkston. Report of the history committee. Clarkston Community Study, Part 4. Clarkston, Washington. BRANDNAMESFOUNDATION 1947 43,000 Years ofpublic Service. Brand Names Foundation, New York. CARSON,GERALD 1965 The Old Country Store. E. P. Dutton, New York. COLCLEASER, DONALDE. 1967 Bottles: Yesterday’s Trash, Today’s Treasures. Old Time Bottle Publishing Company. Salem, Oregon. DAY-AMES. JACOUELINE n.d. Untitled manuscript on the ethnography of Silcott. On file in the Department of Anthropology, Washington State University, Pullman. GAW,LINDAP. 1975 The availability and selection of ceramics in Silcott, Washington, 1900-1930. Northwest Anthropological Research Notes, V O ~ . 9, pp. 166-179. KLEIN,JOELI. 1973 Models and hypothesis testing in historical archaeology. Historical ArchrPology, Vol. 7, pp. 68-77. LEONHARDY, FRANK C. AND JACQUELINEDAYh E S 1975 Silcott, Washington, 1890-1950: Anthropological perspectives on local history. Narrative report submitted to the National Endowment for the Humanities. Department of Anthropology, Washington State University, Pullman. LIPTON,MICHAEL 1968 The theory of the optimizing peasant. Journal of Development Studies, Vol. 4, pp. 327-35 1. LYMAN,RICHARDLEE 1976 A cultural analysis of faunal remains from the Alpowa locality. Master’s Thesis. Washington State University. MEINIG,D. W. 1968 The Great Columbia Plain: A Historical Geography, 1805-1910. University of Washington Press, Seattle. MINER,HORACE 1949 Culture and Agriculture: An Anthropological Study of a Corn-Belt County. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor. MINTZ,SIDNEY 1967 Pratik: Haitian personal economic rela- 112 Nelson Company, New York. tionships. In Peasant Society: A Reader, edited by J. Potter, M. N. Diaz, and G. M. WARD, BARBARA 1967 Cash or credit crops? An examination of Foster. Little, Brown, Boston. some inplications on peasant commercial ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA PERIODICAL PUBLISHERS’ production with special reference on the 1934 Nationally Established Trademark. Periodical multiplicity of traders and middlemen. Publishers’ Association of America, New In Peasant Society: A Reader, edited by York. J. M. Potter, M. N. Diaz, and G. M. Foster. RIORDAN, TIMOTHYB. Little, Brown, Boston. 1976 The Euroamerican component at Alpaweyma SEELY ( 4 5 ~ ~ 8 2 )Master’s . Thesis, Washington WHITE, JAMES 1974 The Hedden’s Store Handbook of ProState University. prietary Medicines. Durham and Downey, n.d. Silcott harvest 1931: a study of the indiPortland, Oregon. vidual through archzology. Northwest Anthropological Research Notes, In Press. WASHINGTON STATEUNIVERSITY JULIAN H. TOWLOUSE, PULLMAN, WASHINGTON 1971 Bottle Makers and Their Marks. Thomas