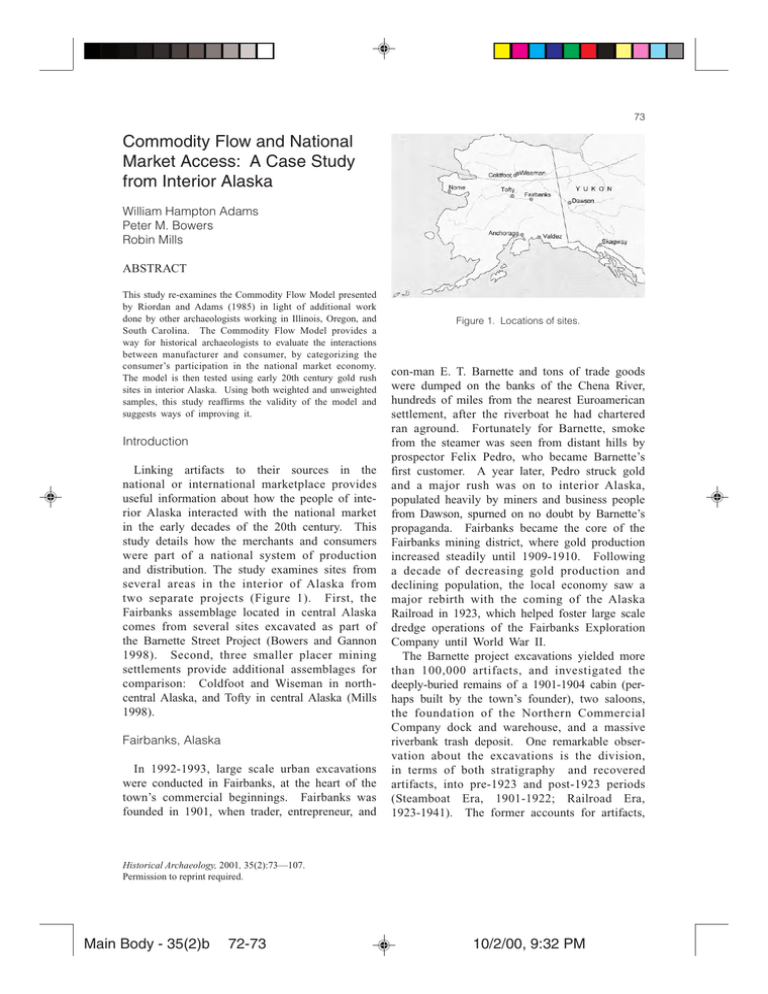

Commodity Flow and National Market Access

advertisement