Critical Steps to Take Before Sending an Officer

advertisement

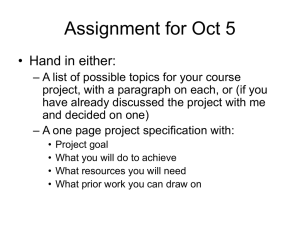

All photos Steven Ruttle Critical Steps to Take Before Sending an Officer CDE #34055 By Rhonda Harper he definition of an emergency is different for each individual— one person’s emergency may be another person’s non-emergency. The 9-1-1 system has only been around since the late 1960s and is still relatively new, so continuing education is critical for both the telecommunicators handling the calls and the general population. Using 9-1-1 In a Jan. 1968 press conference, AT&T announced the designation of the numbers 9-1-1 as a universal emergency number, but it was not until Oct. 1999 that President Clinton signed Senate Bill 800, which finalized 9-1-1 as the nationwide emergency telephone number. 1 That’s a 31.5year span between implementation 24 PUBLIC SAFETY COMMUNICATIONS ∥ ◀ ▶ october 2013 ∥ and finalization, a major gap in the effort to educate the public on the differences between an emergency and a non-emergency. PSAPs field calls every day that are true emergencies: shootings, stabbings and domestic disturbances, to name just a few. But we must also acknowledge the in-progress calls received daily. Some callers dial 9-1-1 to ask for the ◀ ▶ www.apcointl.org ∥ www.apcointl.org ◀ ▶ october 2013 ∥ ◀ ▶ PUBLIC SAFETY COMMUNICATIONS 25 Law Enforcement Communications the primary goal for telecommunicators is to establish which questions are really needed on the various calls received. time, report that their food was made incorrectly, request a polygraph test on a significant other suspected of cheating or to simply report that a neighbor smells and should be made to take a bath (among numerous other unsavory examples). Alternatively, there are callers who will take the time to dial a nonemergency number when an incident is actually occurring, simply because they don’t want to bother anyone. How often do agencies place callers on hold, after being given permission to do so, only to find out the call was in fact an actual emergency needing immediate dispatch? When each of these potential callers has their own perception of what an emergency is or isn’t, how can we get the general public on the same proverbial page? Is it even possible? Public safety emergency services professionals must deal with a substantial gray area when determining whether a call is a true emergency. This essentially means that no two calls may be handled in exactly the same manner. For example, when it comes to Emergency Medical Dispatch (EMD) calls, there’s a specific protocol in place to determine the questions that must be asked and the directions that must be provided to the caller depending on the medical emergency. However, the same isn’t true for requests for law enforcement. When handling these calls, common sense must be utilized as to what questions should be asked and which might not apply to the given set of circumstances. There are numerous tools that can 26 PUBLIC SAFETY COMMUNICATIONS ∥ ◀ ▶ october 2013 ∥ be utilized within each agency. An example would be the APCO Law Enforcement Dispatch Guidecards. These guidecards can be adapted to provide a list of questions that support the needs of an individual agency. However, they still allow room for interpretation and individual judgment, and mainly serve as simple assistance when the telecommunicator is stumped or unsure of where to go next in their questioning. Take, for example, two different emergency calls involving domestic disturbances. The telecommunicator may ask questions regarding vehicle descriptions in one, but skip those questions on the next call if there are no vehicles involved. Thanks to the human element, no two calls are exactly alike. In any given situation, one small caveat can change the course of how the telecommunicator conducts their call questioning or how the call is handled. Ultimately, ◀ ▶ www.apcointl.org Cautionary Tales Regardless of the incident or situation, the single most important question to ask on any call is, “What is the location of the emergency?” Without the location, the next question doesn’t matter because we don’t know where to send our responders. Wording is important here. If the calltaker just asks, “what is your address,” and not “what is the location of the emergency,” the caller may state their home address even if they aren’t there. Once the location has been obtained and confirmed, the base level questions can follow: Who, what, when, how and, importantly, are there any weapons involved? Asking about weapons is a must to ensure responder safety. Even if a caller is extremely calm, it does not necessarily mean that they, or someone else, won’t be holding a weapon when responders arrive. When calltakers skip the basic questions and make assumptions early in the call, mistakes can be made. Any delay can result in serious injury or death and increases the agency’s liability exponentially. It’s an unfortunate reality that we sometimes hear news of 9-1-1 calls gone wrong due to simple mistakes that could have been avoided. Telecommunicators falling asleep at the console, responders sent to the incorrect location because an address was not verified, responders not sent at all because a call was forgotten about, telecommunicators hanging up the phone too early or even sending the wrong type of emergency response—any of these can cause a potentially life-threatening delay. One common problem has been geographical issues resulting from population growth. With new neighborhoods popping up all the time, there are bound to be similar or even identical location names. For telecommunicators working in consolidated agencies and dispatching for multiple service areas, there may be several street names that are the same or very similar from city to city. As we all know, when a call comes in, “seconds save lives,” but if we rush without confirming the exact location of the emergency to report a burglary in progress, but the calltaker recorded the incorrect address and city. Officers responded to the address they were given, and when they arrived to no emergency situation they cleared the scene and dismissed the call. It was not until later that they discovered the grave consequences of the mistake that had been made: the caller had been stabbed several times and died from her wounds. In another well-known case from 2008, a telecommunicator in Fulton County, Ga., received a 9-1-1 call from a woman in respiratory distress. The telecommunicator stayed on the line with the caller after sending responders, but she had misheard the woman’s location and had entered Wells Street instead of Wales Street. The two streets may sound similar, but they are in two different jurisdictions, and the confusion could have been avoided if the calltaker had confirmed the city. Responders eventually arrived at the correct address after the dispatch mistake was discovered, but there had already been a 25 minute delay and the caller had died of a pulmonary embolism.3 In 2010, a 9-1-1 telecommunicator in Oakdale, Calif., dispatched fire units to an address in the wrong jurisdiction after receiving a report of a fire. In this case the same address is duplicated in two cities serviced by the same agency. The wrong city was placed into the system after it was not verified. The mistake was discovered approximately three minutes after the call was received, but when another telecommunicator took on the responsibility of dispatching the appropriate units to the correct city, they dispatched the call on the wrong radio channel. This series of mistakes created a six minute delay in responder arrival.4 Earlier this year in Colorado Springs, a hiker reported seeing a fire smoldering while he was out hiking. The dispatcher told the caller that the Pueblo Forest Service was already aware of the fire and would be on the scene Without the location, the next question doesn’t matter or asking the essential subsequent questions, information can be missed and responders can potentially be sent to the wrong location. Let’s not forget the case study of DeLong vs. Erie County from APCO’s Public Safety Telecommunicators 1, Sixth Edition textbook.2 This was one of the first lawsuits involving public safety telecommunications, but it certainly wasn’t the last. A caller dialed 9-1-1 ∥ www.apcointl.org ◀ ▶ october 2013 ∥ ◀ ▶ PUBLIC SAFETY COMMUNICATIONS 27 Law Enforcement Communications shortly. Unfortunately, this particular fire was a separate incident and the fire service was never notified. The delay in response was enough time for the smoldering fire to grow into a wildfire that burned for three days, destroyed 300 homes and killed two people.5 How often have we received calls from citizens in our jurisdictions that are reporting incidents near a location where we already have a call for service? It’s easy to assume the calls are stemming from the same situation, but what if they aren’t? We must allow each call to stand on its own merits and perform the proper call questioning until it can be determined with certainty that the call is a duplicate or must be entered for dispatch into the system. The risks of improper call handling are too great to disregard. Do Your Due Diligence When dispatching for law enforcement agencies, there are two basic types of calls—emergencies and nonemergencies—and each has different sub-categories that determine which questions need to be asked and which questions may not be necessary. The telecommunicator should remain on the line during any in-progress call, providing it does not place the caller in danger, in order to get continually updated and accurate information to responders. If a situation occurs in which speaking may not be possible, ask the caller to keep an open line even if they must be silent or leave the phone behind if they must flee or hide. The telecommunicator can put themselves on mute so that the phone doesn’t give away the location of a caller in danger—no noise will come through the line, but the calltaker will still be able to hear what is going on in the background and provide valuable information to emergency responders. Just as every caller has their own definition of what constitutes an emergency, the same goes for their description of time. As we all know, time is of the essence and it doesn’t take long for suspects to slip away. One caller may state something “just occurred” if the incident happened within the last couple of minutes or less, while another caller may consider “just occurred” to mean within the last 15 minutes. Providing an accurate description of the time 28 PUBLIC SAFETY COMMUNICATIONS ∥ ◀ ▶ october 2013 ∥ period of each incident allows responders to be on the lookout for potential suspects while en-route to the location. Firefighters and EMS responders are different from law enforcement in that they are not issued weapons to protect themselves, other than possibly mace or pepper spray in some jurisdictions. Unfortunately, mace may not be enough to stop someone from shooting a responder or getting close enough to stab or harm them physically. Providing suspect descriptions to firefighters and EMS personnel not only keeps them safe, it also allows them to keep an eye out while staging and waiting for the scene to become secure. Whether dealing with emergency or non-emergency calls, the same basic questions are universally required. Again, location is the most important question on any call, followed by the basics of who, what, why, how and are there any weapons involved. When dealing with non-emergency ◀ ▶ www.apcointl.org calls, we never know exactly what the caller will be reporting and therefore each question will then spur the next until all appropriate information is obtained. Always remember that emergency calls can also come in over administrative or non-emergency lines. Training & Education The need for 9-1-1 education throughout our communities is paramount in understanding the correct usage of 9-1-1, when to call 9-1-1 and when to utilize non-emergency numbers. Each dispatch agency should have its own set of policies and procedures that dictates how calls are handled. Some agencies are allowed to screen their calls, weeding out those that deal with civil issues or other factors not handled by law enforcement. Other call centers are not given any choice and must take any call requesting an officer, regardless of the situation. At my agency, we try to provide our callers with the proper nonemergency information when they call in on emergency lines for situations that aren’t actually emergencies. Unfortunately, no matter how often we do this, some people continue to dial 9-1-1 for non-emergencies. Still, each call must be taken on its own merit, regardless of how many times we’ve heard from that caller with a false emergency, because ignoring an actual emergency call just one time can place a significant level of liability on both the dispatcher and the agency. We’ve already discussed the risks in making assumptions and not triaging each call as it comes in, so the question then becomes, “How can we avoid all of these negative potential outcomes in the first place?” Institute. Consider hosting a course at your agency, as this not only grants your agency one free training session for confirmed and full classes, but also allows your agency to get to know other agencies from the surrounding areas. Citizens in our jurisdictions believe that when they call for an officer one should appear instantly. How often have we received calls from someone stating they have waited more than 30 minutes, when in actuality they have only been waiting five or 10 minutes? When this occurs, what is your response? To avoid liability and still provide customer service, I generally state, “We have your call, we have not forgotten about you and we will send an officer as soon as one is available.” This allows your caller to understand that we are aware of their call, care about their call, and have not been forgotten about them. This approach will typically assist with most callers. However, we sometimes receive the occasional caller who, regardless of what we say, is only focused on the fact that the officer has not yet arrived. Every caller has their own definition of an emergency The simple truth begins with knowing and understanding the policies and procedures unique to your own agency. The next step is training. This step cannot simply occur once and never be touched on again. Within the public safety profession, technology and our communities are continuously changing, and we must change with them in order to stay ahead of the curve. Knowledge is not necessarily power. We have all worked with, known or recognized people who have been at an agency so long they won’t share information for fear of becoming obsolete. Everyone must learn how to accomplish tasks, not just one individual. Working as a telecommunicator is a team effort. Whether you are the sole dispatcher at your agency or you work with several others on a shift, you are not alone. There is a lot of training available and one great resource is the APCO ∥ www.apcointl.org ◀ ▶ october 2013 ∥ ◀ ▶ The Future As much as we want to help in most situations, we are limited by our resources. So the attitude of, “What’s the big deal, we’ll just send an officer” may overwhelm our available resources. In the current economy, budgets are still being cut and over the past few years something has occurred that I never thought would actually happen: Officers have been laid off from departments across the country. In the end, there is a significant level of liability that accompanies our industry and the jobs we perform every day. Always follow your agency’s policies and procedures and always confirm the location of the emergency. Finally, take a proactive role in community education about 9-1-1 information and the proper usage of this valuable tool. We need to work together to minimize the number of non-emergency calls that tie up emergency lines. ∥PSC∥ PUBLIC SAFETY COMMUNICATIONS 29 Law Enforcement Communications RHONDA HARPER, RPL, is the communications CALEA accreditation manager for the Fort Smith (Ark.) Police Department and an APCO Institute adjunct instructor. Contact her at rhonda. harper@fortsmithpd.org. REFERENCES 1. Allen G. (n.d.) History of 911. Dispatch magazine online. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2013, from www.911dispatch.com/911/history/. 2. APCO. Public safety telecommunicator 1, sixth edition. 3. Bennett DL and Garner M. (Aug. 6, 2008). Ga. woman on phone dies after 911 dispatcher mistake. EMS1.com. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2013, from www.ems1.com/emsproducts/computer-aided-dispatch-CAD/ articles/423354-Ga-woman-on-phone-diesafter-911-dispatcher-mistake/. 4. Botto M. (Dec. 27, 2010). Dispatcher mistakes found after dispatch delay. Dispatch magazine online. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2013, APCO Institute | 351 N. Williamson Blvd. Daytona Beach, FL 32114-1112 | 888-272-6911 | 386-322-2500 Fax: 386-322-9766 | institute@apco911.org | www.apcoinstitute.org $199 CALEA Public Safety Communications Accreditation Manager 34170 Online Starts Jan. 8, 2014 34171 Online Starts May 7, 2014 Communications Center Supervisor, 4th Ed. 34846 Rock Hill, S.C. Oct. 2-4 35434 Online Starts Oct.16 35999 Columbia City, Ind. Oct. 23-25 35435 Online Starts Nov. 13 36234 Oklahoma City, Okla. Dec. 4-6 35436 Online Starts Dec. 4 $349 Communications Training Officer 5th Ed. 35440 Online Starts Oct. 2 35441 Online Starts Oct. 16 36257 Fairfield, Conn. Oct. 21-23 36081 Gaithersburg, Md. Nov. 4-6 35442 Online Starts Nov. 13 35443 Online Starts Dec. 4 Communications Training Officer 5th Ed., Instructor 35421 Online Starts Oct. 9 $349 30 PUBLIC SAFETY COMMUNICATIONS Disaster Operations & the Communication Center 35446 Online Starts Nov. 6 35447 Online Starts Dec. 4 $199 Emergency Medical Dispatcher 5.2 34350 Online Starts Oct. 23 36351 Swansea, Mass. Nov. 5-8 34623 Online Starts Nov. 27 $379 Emergency Medical Dispatch Instructor 34360 Online Starts Oct. 16 34361 Online Starts Nov. 13 34362 Online Starts Dec. 11 $459 EMD Manager 34338 Online 34339 Online 34340 Online $199 Starts Oct. 9 Starts Nov. 6 Starts Dec. 4 $379 Fire Service Communications 1st Ed., Instructor 35416 Online Starts Oct. 9 $459 Starts Oct. 1st Leadership Certificate Program—Registered Public Safety Leader $995** **By invitation only. $459 • APCO Institute Presents Web Seminars $199 ∥ 1. President Nixon signed Senate Bill 800, which finalized 9-1-1 as the nationwide emergency telephone number. a.True b.False 2. A T&T designated the numbers 9-1-1 as a universal emergency number in what year? a.1966 b.1972 c.1968 d.1999 3. One of the first lawsuits involving public safety was: a. Erie vs DeLong County b. DeLong vs Eried County c. DeLong vs Erie County d. Erie County vs DeLong County ◀ ▶ october For a complete list of convenient, affordable seminars on topics vital to your agency, visit www.apcointl.com/institute/webinars.htm. Current APCO members receive a $20 discount. Dates, locations and prices are subject to change.Students who enroll in Institute Online classes will be assessed a $50 Distance Learning fee. Tuition is in U.S. funds. 2013 ∥ ◀ ▶ www.apcointl.org 5. I n 2013 a camper reported possibly leaving a fire smoldering in the Pueblo Forest. a.True b.False 1. Study the CDE article in this issue. 6. P roviding descriptions to firefighters and EMS personnel allows them to watch out for the suspect and report to law enforcement while keeping a safe distance. a.True b.False 7. Emergency calls come in on emergency lines only. a.True b. False 8. Common sense has no place in public safety communications. a.True b.False 9. S enate Bill 800, which finalized 9-1-1 as the nationwide emergency number, was signed into law in which year? a.1968 b.1992 c.2001 d.1999 4. In 2008, a 9-1-1 caller in Fulton County, Ga., died from: a. Pulmonary embolism b.Shooting c.Stabbing d.Fire Using the CDE Articles for Credit Fire Service Communications 1st Ed. 34763 Online Starts Oct. 9 34775 Online Starts Dec. 11 Illuminations 35836 Crisis Negotiations for Telecommunicators 34283 Online Starts Nov. 6 36355 Wyandotte, Mich. Dec. 16 Save More Lives • CDE Exam #34055: Law Enforcement Communications Customer Service in Today’s Public Safety Communications Center $199 34279 Online Starts Oct. 2 35987 Atlanta, Ga. Oct. 14 35376 Online Starts Nov. 6 35383 Missoula, Mont. Nov. 14 36237 Henderson, Ky. Nov. 18 • CLASS SCHEDULE Active Shooter Incidents for Public Safety Communications 34848 Benton Harbor, Mich. Oct.9 35104 Benton Harbor, Mich. Oct. 10 36214 Batavia, N.Y. Oct. 15 34939 Manheim, Pa. Oct. 16 35373 Online Starts Oct. 16 36272 Weston, W.Va. Oct. 22 36246 Mundelein, Ill. Nov. 5 35374 Online Starts Nov. 6 36185 Warrenton, Va. Nov. 12 35842 Lake Mary, Fla. Nov. 19 36353 Wyandotte, Mich. Dec. 2 from www.911dispatch.com/2010/12/27/ dispatcher-mistakes-found-after-dispatchdelay/ and http://pdf.911dispatch.com. s3.amazonaws.com/oakdale_fire_review. pdf. 5. Hendrick T. (April 30, 2013). Report: 911 dispatcher made mistake reporting Waldo Canyon Fire. Fox 31 Denver. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2013, from http://kdvr.com/2013/04/30/ report-911-dispatcher-made-mistake-reporting-waldo-canyon-fire/. 1 0. What is the most important question to ask on any call? a. Who is involved? b. What is going on? c. Where is the location of your emergency? d. Are there any weapons involved? Ordering Information: If you are APCO certified and will be using the CDE tests for recer­tification, complete this section and return the form when you send in your request for recertifi­cation. Do not send in the tests every month. There is no cost for APCO-certified personnel to use the CDE article program. 2.Answer the test questions online or using this form. Photocopies are acceptable, but don’t enlarge them. APCO Instructor Certificate # 3.Fill out the appropriate information section(s), and submit the form to: APCO EMD Basic Certificate # APCO Institute 351 N. Williamson Blvd. Daytona Beach, FL 32114 Questions? Call us at 888/APCO-9-1-1. You can now access the CDE Exam online! Go to http://apco.remote-learner. net/login/index.php to create your username and password. Scroll down to ”CDE Magazine Article Exams” and click on “Public Safety Communications Magazine Article Exams”; then click on “The Morning After Narrowbanding (34051)” to begin the test. Once the test is completed with a passing grade, a certificate is available by request for $15. Expiration Date: Expiration Date: If you are not APCO certified and would like to use the CDE tests for other certifications, fill out this section and send in the completed form with payment of $15 for each test. You will receive an APCO certificate in the mail to verify test completion. (APCO instructors and EMD students please use section above also.) Name: Title: Organization: Address: Phone:Fax: E-mail: I am certified by: ❑ MPC ❑ PowerPhone ❑ Other If other, specify: ❑ My check is enclosed, payable to APCO Institute for $15. ❑ Use the attached purchase order for payment. ∥ www.apcointl.org ◀ ▶ october 2013 ∥ ◀ ▶ PUBLIC SAFETY COMMUNICATIONS 31