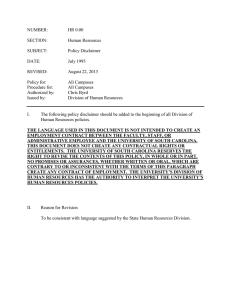

Contract Disclaimers in ERISA Summary Plan Documents: A

advertisement