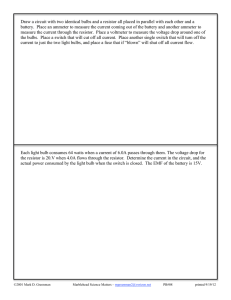

Topics: Parallel circuits, current sources

advertisement