A Landowner`s Guide to Leasing Land for Farming

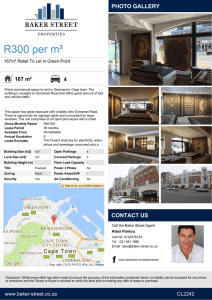

advertisement