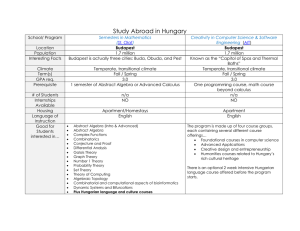

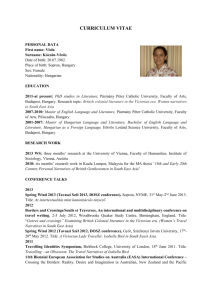

Hungary

advertisement