Department of Homeland Security Department of Agriculture

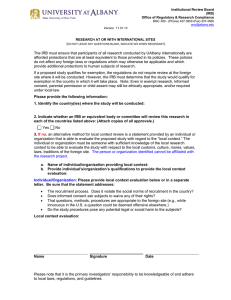

advertisement