Family School Partnership Toolkit - Colorado Springs School District

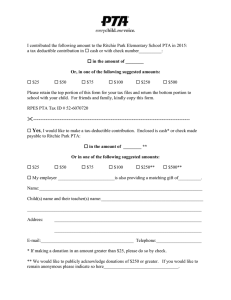

advertisement