Reforming Relationships: School Districts, External Organizations

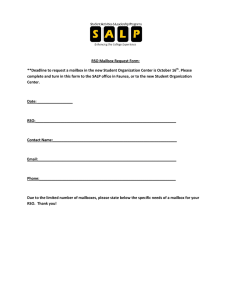

advertisement