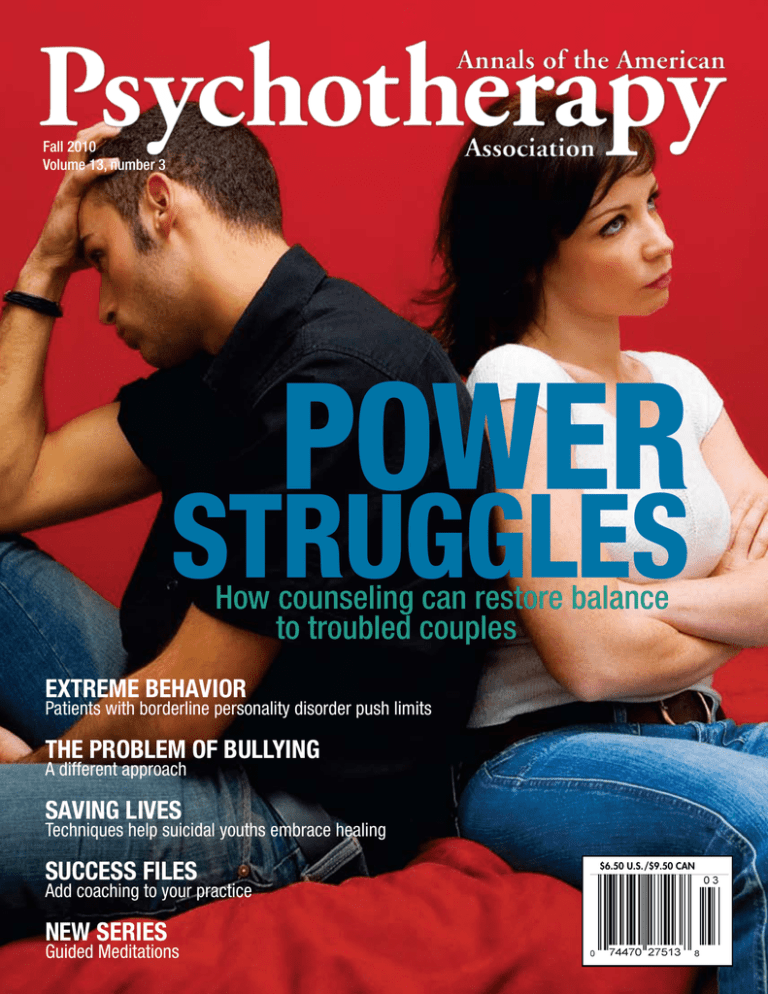

Fall 2010

Volume 13, number 3

Power

Struggles

How counseling can restore balance to troubled couples

Extreme Behavior

Patients with borderline personality disorder push limits

The Problem of Bullying

A different approach

Saving Lives

Techniques help suicidal youths embrace healing

success Files

Add coaching to your practice

New series

Guided Meditations

$6.50 U.S./$9.50 CAN

BCPC0310AN

You entered the field to help people.

When was the last time an organization

provided any real help to you?

Benefits of Membership

BECOME A Board Certified

Professional Counselor

• Free subscription to our quarterly

peer-reviewed journal, Annals of the

American Psychotherapy AssociationSM

• FREE online continuing education credits

• Discounted rates to our annual National

Conference

Our Mission

• Advocacy at the state and national levels

The mission of the American Board of Professionals Counselors (ABPC) is to be the

nation’s leading advocate for counselors. We will work with you to protect your right

to practice, increase parity for your profession, and provide you with the recognition,

validation, and fairness you so richly deserve. ABPC will champion counselors’ right

to practice.

SM

The prestigious Board Certified Professional CounselorSM credential will set you apart

as being an accomplished, competent, and dedicated mental health professional.

By joining the American Psychotherapy Association® as a Board Certified Professional

CounselorSM, you are joining more than an association. You become a member of a

community of counselors dedicated to working together not only to better serve

your clients, but also to support one another in your professional development.

2 ANNALS Fall 2010

• A listing on the Find a Therapist national

referral service

• Networking opportunities with other

mental health professionals and association

members of ACFEI, AAIM, and ABCHS

• Discounts on professional liability, auto, life,

and homeowner insurance

www.americanpsychotherapy.com

(800) 592-1125

www.americanpsychotherapy.com

Have You Written a Book?

Publish it with US!

Establish your expertise and earn instant credibility by publishing your own

book or research. Market to your niche audience at conferences, trade shows,

or online—your distribution options are endless!

We can offer you a full array of customized and complete publishing services, including:

•High-quality book designs

•Choose your own cover, art, and photos or let our designer do it!

•Hardcover, softcover, and full-color options available

•Print on demand—no minimum orders or storage fees

•Retain all copyrights to your book

•Your book will never go out of print

•Publish QUALITY and QUICKLY

For complete details call

Cary Bates at (877) 219-2519 ext. 131

or e-mail at: cary@acfei.com

BP0310AN

BP0310AN

Culture Notes

is now a book!

Culture Notes: Essays on Sane Living collects a decade’s

worth of wisdom from Annals columnist Irene Rosenberg

Javors. Within her plainspoken essays, the reader finds a

prescription for “sane living” to counteract the negative

messages with which society continually bombards us.

Practically anyone can benefit from a dose of what Javors

recommends: moderation, compassion, critical thinking,

and resiliency in the face of life’s challenges.

Get your copy today!

(800) 592-1125

CALL (800) 205-9165 to order

on sale

now!

14.95

$

Fall 2010 ANNALS 3

CONTACT

PHONE:

(800) 592-1125

WEB:

www.americanpsychotherapy.com

Become a member of the American Psychotherapy

Association. We provide mental health professionals with the tools necessary to be successful and

build stronger practices. Annual membership dues

are $165. For more information, or to become a

member, call us toll-free at (800) 592-1125 or visit

www.americanpsychotherapy.com.

2010 EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD

Debra L. Ainbinder, PhD, NCC, LPC, BCPC

Janeil E. Anderson, LCPC, BCPC, DBT

Edward Michael Andrews, MEd, LPC, NCC

Kelley Armbruster, MSW, LISW, DAPA

Diana Lynn Barnes, PsyD, LMFT

Cherie J. Bauer, MPS

Phyllis J. Bonds, MS, NCC, LMHC

Sabrina Caballero, LCSW, DAPA

Sarah Campbell, PhD

Stacy L. Carter, PhD, BCPC

Mary Helen McFerren Morosko Casseday, LMFT, CHT

Susanne Caviness, PhD, LMFT, LPC

Peter W. Choate, MSW, DAPA, MTAPA

Linda J. Cook, LCSW, CRS, DAPA, BCETS

John Cooke, PhD, LCDC, FAPA

Clifton D. Croan, MA, LPC, DAPA

Catherine J. Crumpler, MA, LPC, BCPC

Charette Dersch, PhD, LMFT

David R. Diaz, MD

Heather Irene DiDomenico, LPC, BCPC

Carolyn L. Durr, MA, LPC

John D. “Jodey” Edwards, MA, MS, NCC, LPC

Adnan Mohammad Farah, PhD, BCC, LPC

Patricia Frank, PsyD, FAPA

Natalie Hill Frazier, PhD, LPC

Sabrina Friedman, EdD, CNS-BC, FNP-C

Robert Raymond Gerl, PhD

Rebecca Godfrey-Burt

Sam Goldstein, PhD, DAPA

Jacqueline R. Grendel, MA, LPC, BCPC

Richard A. Griffin, EdD, PhD, ThD, DAPA

Therese Grolly, BCPC, LPC

Yuh-Jen Guo, PhD, LPC, NCC

Lanelle Hanagriff, MA, LPC, FAPA

Noah Hart, Jr., EdD, DAPA

Ray L. Hawkins, PhD, LPC, AAMFT

Gregory Benson Henderson, MS

Douglas Henning, PhD

Mark E. Hillman, PhD, DAPA

Elizabeth E. Hinkle, LPC, LMFT, NBCC

Ronald Hixson, PhD, LPC, DAPA, BCPC

Judith Hochman, PhD

Antoinette C. Hollis, PhD

Irene F. Rosenberg Javors, MEd, DAPA

Gregory J. Johanson, PhD

Michael E. Jones, MA, LMFT, BCPC, CFC

Laura W. Kelley, PhD

Gary Kesling, PhD, FAAMA, FAAETS

C.G. Kledaras, PhD, ACSW, LCSW

Michael W. Krumper, LCSW, DAPA

Ryan LaMothe, PhD

Allen Lebovits, PhD

Poi Kee Frederick Low, MS, BS

Kathryn Lowell, MA, LPCC

Edward Mackey, PhD, CRNA, MS, CBT

Frank Malone, PsyD, LMHC, LPC, FAPA

Beth McEvoy-Rumbo, PhD

Thomas C. Merriman, EdD, SBEC

(Virginia) Ginger Arvan Metcalf, MS, RN

Yvonne Alleen Moore, MC, BCPC

William Mosier, EdD, PA-C

Natalie H. Newton, PhD, DAPA

Kim Nimon, PhD

Deborah Norton, MSA, LMHC

Donald P. Owens, Jr., PhD

Thomas J. Pallardy, PsyD, BCPC, LCPC, CADC

Larry H. Pastor, MD, FAPA

Richard Ponton, PhD

Joel G. Prather, PhD, MS, BCPC,

Helen Diann Pratt, PhD

Ahmed Rady, MD, BCPC, FAPA, DABMPP

Daniel J. Reidenberg, PsyD, FAPA, CRS

Roger E. Rickman, PhD,ThD, FAPA, CRS

Arnold Robbins, MD, FAPA

Arlin Roy, MSW, LCSW

Maria Saxionis, LICSW, LADC-I, CCBT, CRFT

Alan D. Schmetzer, MD, FAPA, MTAPA

Paul Schweinler, MDiv, MA, LMHC, DAPA

Bridget Hollis Staten, PhD, CRC, MS, MA

Suzann Steadman, PsyD

Ralph Steele, BCPC

Moonhawk River Stone, MS, LMHC

Mary Elise Taggart, LPC

Patrick Odell Thornton, PhD

Mary A.Travis, PhD, EdS, MA, BS

Charles Ukaoma, PsyD, PhD, BCPC, DAPA

Angela von Hayek, PhD, LMFT, LPC

Gene W. Walters, DSW, LCSW

Melinda Lee Wood, LCSW, DAPA

Rosemarie Zlotnick

Cecilia Zuniga, PhD, BCPC

Annals of the American Psychotherapy Association (ISSN 1535-4075) is published quarterly by the American Psychotherapy

Association. Annual membership for a year in the American Psychotherapy Association is $165. The views expressed in

Annals of the American Psychotherapy Association are those of the authors and may not reflect the official policies of the

American Psychotherapy Association. Abstracts of articles published in Annals of the American Psychotherapy Association

appear in e-psyche, Cambridge Scientific Database, PsycINFO, InfoTrac, Primary Source Microfilm, Gale Group Publishing’s InfoTrac Database, Galenet, and other research products published by the Gale Group.

Contact us:

Publication, editorial, and advertising offices at 2750 E. Sunshine St., Springfield, MO 65804. Phone: (417) 823-0173, Fax:

(417) 823-9959, E-mail: editor@americanpsychotherapy.com.

Postmaster:

Send address changes to American Psychotherapy Association, 2750 E. Sunshine St., Springfield, MO 65804.

© Copyright 2010 by the American Psychotherapy Association. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be distributed or otherwise used without the expressed written consent of the American Psychotherapy Association.

4 ANNALS Fall 2010

FOUNDER & PUBLISHER:

Robert L. O’Block, MDiv, PhD, PsyD, DMin

(rloblock@aol.com)

President & Chief Executive Officer

John H. Bridges III, DSc (Hon), CHMM, FACFEI

EDITOR IN CHIEF:

Christopher Powers (cpowers@americanpsychotherapy.com)

ANNALS EDITOR:

Laura Johnson (laura@americanpsychotherapy.com)

INSIDE HOMELAND SECURITY® EDITOR:

Ed Peaco (ed@abchs.com)

ADVERTISING:

Laura Johnson (laura@americanpsychotherapy.com)

(800) 205-9165 ext. 157

ACTING CHIEF ASSOCIATION OFFICER:

Tania Miller (tmiller@acfei.com)

GRAPHIC DESIGNER:

Cary Bates (cary@acfei.com)

EXECUTIVE ADVISORY BOARD

CHAIR:

Daniel J. Reidenberg, PsyD, FAPA, MTAPA, CRS

VICE CHAIR:

Alan D. Schmetzer, MD, FAPA, MTAPA

CHAIR EMERITUS: Michael A. Baer, PhD, FAPA,

MTAPA, CRS

MEMBERS EMERITUS:

William Glasser, MD, MTAPA, FAPA

Bill O’Hanlon, MS, FAPA, LMFT, MTAPA

MEMBERS:

John Catlett Jr., MEd, BCPC

Peter W. Choate, MSW, DAPA, MTAPA

Fay Maria Hart, FAPA, BCPC, ACMC-III, MTAPA

Noah Hart Jr., EdD, DAPA

Natalie Hill Frazier, PhD, LPC

Ron Hixson, PhD, LPC, DAPA, BCPC

Stephen R. Lankton, MSW, DAHB

Luniece E. Obst, MEd, LPC, BCPC

Frances A. Clark-Patterson, PhD

Joel G. Prather, MS

Michael E. Reynolds, DMin, FAPA

Lori N. Simons, PhD

William Martin Sloane, PhD, LLM, BCPC, FAPA

Wayne E.Tasker, PsyD, DAPA, BCPC

CONTINUING EDUCATION

The American College of Forensic Examiners

International (ACFEI), sister organization to the

American Psychotherapy Association, provides continuing

education credits for accountants, nurses, physicians, dentists,

psychologists, psychiatrists, counselors, social workers, and

marriage and family therapists.

ACFEI is an approved provider of continuing education

by the following:

Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education

National Association of State Boards of Accountancy

National Board for Certified Counselors

California Board of Registered Nursing

American Psychological Association

California Board of Behavioral Sciences

Association of Social Work Boards

American Dental Association (ADA CERP)

Diplomate status with the American Psychotherapy Association

is recognized by the National Certification Commission.

For more information on recognitions and approvals, please

visit www.americanpsychotherapy.com

www.americanpsychotherapy.com

The American Association of Integrative Medicine (AAIM) recognizes that a multidisciplinary approach to medicine provides the maximum therapeutic benefit. AAIM’s advocacy

for broader treatment options facilitates a bond between integrative and Western medicine, and

the end result is a gathering place for healers, educators, and researchers from all specialties to

compare notes and combine forces, benefiting both the patient and the health care provider.

Become a member today!

AAIM0310AN

APA0310AN

The American Psychotherapy Association® is a membership society for psychotherapists of many different disciplines.

The association’s purpose is to establish a cohesive national

organization that advances the mental-health profession by

elevating standards through education, basic and advanced

training, and by offering credentials to ethical, highly

educated, and well-trained psychotherapists.

The American Psychotherapy Association currently

offers the following certifications and designations:

• Board Certified Professional Counselor, BCPCSM

• Certified Relationship Specialist, CRS®

• Certified in Hospital PsychologySM

• Certified in the Psychology

of Terrorists, CPTSM

• Diplomate

• Fellow

• Master Therapist®

(800) 592-1125 • www.americanpsychotherapy.com

UNITE FOR A STRONGER PROFESSION BY JOINING TODAY!

FALL 2010 • VOLUME 13, NUMBER 3

44

cover story

Lack of equity or an

imbalance of power can

be a major source of

discontent in relationships.

“Couples

Counseling:

Re-establishing

Balance and Equity”

presents possible interventions

to restore the balance of power.

features

14

Conscience Sensitive Psychiatry,

Clinical Applications: Retrieval and

Incorporation of Life-Affirming Values

in a Personalized Suicidality

Management Plan

By Matthew R. Galvin, MD, Barbara M. Stilwell, MD, and Jerry Fletcher, MD

24

Cognitive Processing Therapy for PTSD

By Tanja Kern

66

6 ANNALS Fall 2010

28

Prescriptive Photomontage: A Process

and Product for Meaning-Seekers with

Complicated Grief

By Nancy Gershman, BA, and Jenna Baddeley, MA

www.americanpsychotherapy.com

departments columns/case studies

10

08 Mind News

13 New Members

37 NEW!

Success Files: Add Coaching to Your Practice

By Laura Johnson, Annals editor

Short Story: “Trial Period”

By James McAdams

56

NEW!

Meditation Series

By Eve Eliot

65 Book Reviews

80CE Test Pages

43

Culture Notes: Focus, Focus, Focus!

By Irene Rosenberg Javors, MEd, LMHC, DAPA

58

Rx Primer: Overview of ADHD

By Ayesha Sajid, MD, Maria C. Poor, MD, and David R. Diaz, MD

66

Chaplain’s Column: Chaplains as Subject Matter

Experts: A Valuable Untapped Resource

By Chaplain David Fair, PhD, CHS-V, ACMC-III

70

Member Spotlight

Francesca Starr

77

Practice Management:

Return on an Educational Investment

By Ronald Hixson, PhD, LPC, LMFT, BCPC

56

43

38

The Use of Hypnosis in the Treatment of

Migraine Headache: A Case Study

By Edward F. Mackey, CRNA, MSN, PhD

44

Couples Counseling: Re-establishing Balance and Equity

By Don Pazaratz, EdD, LPsych

51

The Scapegoat Archetype and the Need to be Right:

Depth Approaches in Organizational Cultures

By Michael Staples, RT(T), MFT, and Valerie Hinard, MA, MFT intern

60

(800) 592-1125

60

Depression School:

A Three-Session Group Crisis Stablization Intervention

By Jolene Oppawsky, PhD, LPC, ACS, DAPA

72

Patient Safety of the Borderline Personality on the Crisis Unit

By Robert Mead, Jr., LMFT, BCPC, DAPA, doctoral intern

74

Guest Column: A Powerful Psychotherapeutic Approach

to the Problem of Bullying

By Israel “Izzy” Kalman, MS, NCSP

Fall 2010 ANNALS 7

MIND NEWS

Real Partners Are No Match for Ideal Mates

Our ideal image of the perfect partner differs greatly from our real-life

partner, according to new research

from the University of Sheffield

and the University of Montpellier

in France. The research found that

our actual partners are of a different height, weight, and body mass

index than those we would ideally

choose. The study, which was published

the week of September 27, 2010

in the journal PLoS ONE, found that most men and women express different mating preferences for body morphology than the actual morphology of their partners, and the discrepancies between real mates and fanta-

sies were often larger for women than for men. The study also found that

most men would rather have female partners much slimmer than they really have. Most women are not satisfied, either, but contrary to men, while

some would like slimmer mates, others prefer bigger ones.

Dr. Alexandre Courtiol, from the University of Sheffield, who carried

out the work with colleagues from the Institut des Sciences de l’Evolution

de Montpellier, said: “Whether males or females win the battle of mate

choice, it is likely for any trait, what we prefer and what we get, differs

quite significantly. This is because our ideals are usually rare or unavailable

and also because both sexes express preferences while biological optimum

can differ between them.”

University of Sheffield (2010, October 1). Real partners are no match for

ideal mate, study finds. ScienceDaily. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedaily.com­/

releases/2010/10/101001105517.htm

Loners, Antisocial Kids Become Targets of Peer Victimization

Loners and antisocial kids who

reject other children are often bullied at school—an

accepted form of punishment from

peers as they establish social order.

Such peer victimization may be an

extreme group response to control renegades, according to a new

study from Concordia University

published in the Journal of Early

Adolescence.

“For groups to survive, they need

to keep their members under control,” said author William M. Bukowski, a professor at the Concordia

Department of Psychology and director of its Centre for Research in Human

Development. “Withdrawn individuals threaten the strong social fabric of

a group, so kids are victimized when they are too strong or too antisocial.

Victimization is a reaction to anyone who threatens group harmony.”

Bukowski, who observed many instances of peer victimization in

his previous career as a math teacher in elementary and high schools, said

educators and parents can help protect children from being victimized and

prevent alpha-kids from becoming bullies.

“No one wants to blame the victim, so teachers and parents always

focus on bullies, but it’s important to treat symptoms in peer victimization

and not only the causes,” he said.

To prevent victimization in classrooms and help neutralize bullying,

teachers should foster egalitarian environments, where access to power is

shared, he continued. “Parents and educators should also encourage children who are withdrawn to speak up and assert themselves.”

Concordia University (2010, September 28). Rebels without applause: New study

on peer victimization. ScienceDaily. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedaily.com/

releases/2010/09/100928111126.htm

Control of Work Schedule Can Blur Boundaries

Is there a downside to schedule

control at work? According to new

research out of the University of

Toronto, people who have more

schedule control at work tend

to report more blurring of

the boundaries between

work and the other parts of

their lives, especially familyrelated roles.

Researchers measured the extent of schedule control and its

impact on work-family processes

using data from a national survey of more than 1,200 American workers. Sociology professor Scott

Schieman (U of T) and PhD student Marisa Young (U of T) asked study

participants: “Who usually decides when you start and finish work each

day at your main job? Is it someone else, or can you decide within certain

8 ANNALS Fall 2010

limits, or are you entirely free to decide when you start and finish work?”

Schieman says, “Most people probably would identify schedule control

as a good thing—an indicator of flexibility that helps them balance their

work and home lives. We wondered about the potential stress of schedule

control for the work-family interface. What happens if schedule control

blurs the boundaries?”

The authors describe two core findings:

• People with more schedule control are more likely to work at home and

engage in work–family multitasking activities; that is, they try to work on

job- and home-related tasks at the same time while they are at home.

• In turn, people who report more work-family role blurring also tend to

report higher levels of work-family conflict—a major source of stress.

University of Toronto. A downside to work flexibility? Schedule control and its link

to work-family stress. Retrieved from http://media.utoronto.ca/media-releases/

a-downside-to-work-flexibility/

www.americanpsychotherapy.com

Tennis Grunting Interferes With Opponent’s Performance

You’ve heard them at tennis matches—a loud, emphatic grunt with each player’s stroke. A University of

Hawaii at Manoa researcher has studied the impact of these grunts and come up with some

surprising findings.

Scott Sinnett, assistant psychology

professor at the University of Hawaii at

Manoa, has co-authored a study on the potential detrimental effect that noise has on

shot perception during a tennis match.

Sinnett’s work appears in the October

1 online issue of PLoS ONE, published by

the Public Library of Science. He co-authored

the study with Alan Kingstone, psychology professor at

the University of British Columbia, to determine if it is

reasonable to conclude that a tennis grunt interferes with an opponent’s

performance.

As part of the study, 33 undergraduate students from the University

of British Columbia viewed videos of a tennis player hitting a ball to either

side of a tennis court; the shot either did or did not contain a brief sound

that occurred at the same time as contact. Participants were required to respond as quickly and accurately as possible, indicating the direction of the

shot in each video clip on a keyboard. The extraneous sound resulted in

significantly slower response times and significantly more decision errors,

confirming that both response time and accuracy are negatively affected.

University of Hawaii at Manoa (2010, October 1). Tennis grunting: study reveals

surprising effects. ScienceDaily. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedaily.com/

releases/2010/10/101003081714.htm

Reseacher Finds Vicious Cycle in Overeating and Obesity

New research provides

evidence of the vicious cycle

created when an obese individual overeats to compensate

for reduced pleasure from food.

Obese individuals have fewer

pleasure receptors and overeat

to compensate, according to a

study by University of Texas at

Austin senior research fellow

and Oregon Research Institute

senior scientist Eric Stice and

his colleagues published in The

Journal of Neuroscience. Stice

shows evidence this overeating

may further weaken the responsiveness of the pleasure receptors (“hypofunctioning reward circuitry”),

further diminishing the rewards gained from overeating.

Food intake is associated with dopamine release. The degree of pleasure derived from eating correlates with the amount of dopamine released.

Evidence shows obese individuals have fewer dopamine (D2) receptors in

the brain relative to lean individuals and suggests obese individuals overeat

to compensate for this reward deficit. People with fewer of the dopamine

receptors need to take in more of a rewarding substance—such as food or

drugs—to get an effect other people get with less.

“Although recent findings suggested that obese individuals may experience less pleasure when eating, and therefore eat more to compensate,

this is the first prospective evidence to show that the overeating itself further blunts the award circuitry,” says Stice, a senior scientist at Oregon

Research Institute, a nonprofit, independent behavioral research center.

“The weakened responsivity of the reward circuitry increases the risk for

future weight gain in a feed-forward manner. This may explain why obesity typically shows a chronic course and is resistant to treatment.”

University of Texas at Austin (2010, September 30). Research examines vicious cycle of overeating and obesity. ScienceDaily. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedaily.

com/releases/2010/09/100929171819.htm

Study: Prescriptions Pave Way to Street Drug Addiction

If you want to know how people become addicted and why

they keep using drugs, ask the

people who are addicted.

Thirty-one of 75 patients

hospitalized for opioid detoxification told University at Buffalo

physicians they first got hooked

on drugs legitimately prescribed

for pain. Another 24 began with

a friend’s left-over prescription

pills or pilfered from a parent’s medicine cabinet. The remaining 20

patients said they got hooked on street drugs.

However, 92 percent of the patients in the study said they eventually

bought drugs off the street, primarily heroin, because it is less expensive

and more effective than prescriptions. They continued using drugs because

(800) 592-1125

they “helped to take away my emotional pain and stress,” “to feel normal,”

“to feel like a better person.”

Results of the study appeared in Journal of Addiction Medicine. The information will be used to train medical students and residents at the UB School

of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences and practicing physicians to screen for

potential addiction among their patients, and to perform an intervention or

refer for treatment before an addiction becomes life-threatening.

“We are seeing an increase in the number of patients addicted to prescription drugs,” says Richard Blondell, MD, professor of family medicine

and senior author on the study, “so we wanted to better understand how

they first got hooked.”

University at Buffalo (2010, August 21). Drug addicts get hooked via prescriptions,

keep using ‘to feel like a better person,’ research shows. ScienceDaily. Retrieved from

http://www.sciencedaily.com­/releases/2010/08/100820145307.htm

Fall 2010 ANNALS 9

SUCCESS FILES - Practice Building

Add

Coaching

to your practice

By Laura Johnson, Annals editor

Coaching is a booming and potentially

lucrative field—and few people are better positioned than mental

Some of the many niches of coaching

health professionals to expand or even completely transition their

• ADHD

• Life/personal

practices into coaching. Many of the skills necessary to be a good

• Career and career transition

• Organizational

coach go hand-in-hand with psychotherapy: effective listening, facili-

• Confidence

• Parenting

tating change, re-framing, and good problem-solving, to name a few.

• Conflict

• Performance

• Corporate

• Public speaking

• Creativity

• Relationship

• Dating

• Retirement

• Diversity

• Sales

• Divorce

• Small business

• Executive

• Spiritual

• Financial

• Sports

• Health/fitness/wellness

• Success

• Industry-specific

• Time management

• Interview

• Transformational

• Leadership/management

• Women (midlife, empty nest)

Coaching may emerge naturally out of a clinical practice. Although

there are distinct differences between the two professions, it is possible to practice both—and many therapists choose to do just that.

For California-based divorce coach Marvin Chapman, PsyD, MFT,

CFC, BCPC, a divorce and custody battle was the impetus for his

decision to go back to school to become a marriage and family therapist. Within a few years, he also began working with men as a divorce coach in a new, non-adversarial paradigm called Collaborative

Divorce. Chapman said he believes adding divorce coaching to a

practice can be beneficial to marriage and family therapists—both

financially for the therapist and emotionally for clients.

John W. Carney, MA, BCPC, has practiced psychotherapy for

20 years. He has a full-time position in corporate training and is

also executive director of Life Coaching & Empowerment, LLC.

The ability to reach a greater number of people was one factor in

his career shift from counseling to coaching. The positive power of

coaching was another: “With coaching, it just simply evokes a real

dynamic hope at a deep level...That is coaching’s forté,” said Carney,

whose coaching practice is in Houston, Texas.

Although coaching can be done in person, coaches may choose

to work with their clients by phone and Web-based technologies,

potentially allowing them to work from anywhere.

Anne D. Gooding, PhD, wrote a series of articles on coaching for

Annals from 2003–2007. Asked to reflect on changes she has noticed

since that time, Gooding said many mental health professionals felt

10 ANNALS Fall 2010

www.americanpsychotherapy.com

same client. Chapman said, “I do not personally engage in both

therapy and coaching with the same client...In my mind, coaching

and therapy with the same client is a dual role, dual relationship,

that would compromise the integrity, meaning, and outcome of

both processes.”

Carney, on the other hand, said, “I will dip in and out...and let

(the client) know that I am doing that, between psychotherapy

counseling and coaching, and I would typically go for the deeper, stronger, broader perspective, and so it’s a more full approach.”

However, if Carney determines that he doesn’t have the time or desire to work as a therapist with the client, he can easily refer that

client to another professional.

A common criticism of coaching is the relative lack of regulatory oversight and standardized licensing requirements—legally,

almost anyone with minimal training can call himself a life coach.

However, that could change as the field evolves. Chapman said he

believes both the International Association of Coaching and the

International Coach Federation are headed in the direction of licensure for accountability reasons. For the protection of the consumer,

“I do believe a license should be required in order to practice coaching,” Chapman said. Carney agrees that the field is moving toward

licensure, “but it’s not going to be anytime real soon.”

Bette Alkazian, a California therapist who specializes in parenting

issues, said that because of ethical concerns, she always suggests

that people who are looking for a coach go to someone who is

certified. “As a therapist, I always follow the rules bound by my license even when I’m wearing more of a coaching hat.”

Although many organizations offer training and credentials

for coaches, the International Coaching Federation, the Coaches

Training Institute, and the International Association of Coaching

are particularly big names in the field.

Carney’s take on making the leap into coaching: “Maybe a person

has been a psychotherapist for 5, 10, 15, 25, maybe 40 years, but

maybe they’ve lost focus. Maybe they’ve got so busy for a while that

they would like to be able to take a step back and dream again. What

is something that they’ve always wanted to do and have a little bit

of a fresh start going into something? And then, what professional,

unique aspects can come about specifically in your life, personally

and professionally, because of coaching that psychotherapy is not

allowing for you? Now, that is the question to search for.”

threatened then—concerned that life coaches were taking clients

away. Now, she said, coaching has become the “new kid on the block,”

and she continues to recommend that therapists provide coaching.

“People seemingly are more ready to accept coaching, especially if

provided by a trained mental health professional,” Gooding said.

While it may be tempting to simply add “life coach” or some other coaching niche to your listed areas of specialization, that is exactly

the wrong way to go about making the transition, Carney said. He

is impassioned on this topic: “Just because the field doesn’t currently

require a license doesn’t mean that just as much training shouldn’t go

into it as psychology. It should. If you are going to become a professional life coach, then you need to go ahead and figure on investing

what would be equivalent to at least a full two years through some

type of training program.”

One resource that Carney recommends for therapists exploring

the option of transitioning into coaching is the Web site of Linda

Hedberg, www.christiancoachingresources.com. Hedberg is the

author of The Complete Guide to Christian

Coach Training. “She’s all about simply get- While coaching and counseling are both “helping” professions,

ting professional, top level of quality of re- there are distinct differences between the two:

sources out to folks that are just investiC o unselin g

vs.

C o a c h in g

gating the field. And it doesn’t have to be

Counselor is the expert

Coach and client are partners

Christian—just in general as well,” he said.

Tends to reflect on past

Tends to look toward future

Gooding suggests that those interested in

coaching “read, read, read, and attend semiExplores emotions

Solution- and goal-driven

nars, teleconferences, write articles, and give

Emphasis on relationships

Emphasis on individual

presentations.” She also recommends using

Focus on correcting perceived problems or

Focus on achieving excellence

the services of a coach to help make the tranaddressing dysfunctions

sition. “It’s similar to being in therapy as you

May be reimbursed by insurance

Self-pay

train to become a therapist. The experience

May

continue

for

years

Usually short-term

is invaluable,” she said.

Coaches interviewed for this article were

Helps those with mental illness

Does not diagnose or treat mental illness

divided on whether it is appropriate to use

Seeks closure

Seeks possibilities

both counseling and coaching with the

(800) 592-1125

Fall 2010 ANNALS 11

Dr. Daniel Reidenberg,

chair of the American

Psychotherapy

Association’s Executive

Advisory Board, had

even more on his plate

than usual in the days

leading up to the 2010

National Conference in

Orlando, Florida, where

he was keynote speaker

at the annual banquet.

Reidenberg was among those leading efforts for World Suicide

Prevention Day in the United States and worldwide. His work included

developing a Web site—www.take5tosavelives.org—with an accompanying Facebook event and Twitter page. Reidenberg also spoke to the

National Press Club in Washington on the day itself, September 10.

Just days before, he gave a presentation in Rome with Dr. Jerry Reed

at ESSSB13, the 13th edition of the European Symposium on Suicide

and Suicidal Behavior. A half-dozen fundraising events were also in the

mix during the weeks preceding his trip to Rome.

Suicide prevention is a cause with which Reidenberg is deeply involved. He is executive director of Suicide Awareness Voices of

Education (SAVE), one of the nation’s first organizations dedicated to

12 ANNALS Fall 2010

the prevention of suicide. Reidenberg is also managing director of the

National Council for Suicide Prevention and is the U.S. representative

for the International Association for Suicide Prevention (IASP).

His presentation at ESSSB13—titled “Preventing Suicide Beyond 2010:

What Do We Need to Know?”—addressed challenges in the suicide

prevention field as it grows and changes. Some of the questions he

poses: Are we asking the right questions? Is the research focusing in

the right direction? Do we overly rely on “our history” and the early

work of the experts in the field without asking the provocative questions to inform our future? Are we really listening to enough people

who might hold the clues to what prevents suicide? Are there particular selected and indicated approaches we should turn our attention to

with the promise of lives saved?

The theme for World Suicide Prevention Day 2010 was “Many Faces,

Many Places: Suicide Prevention Across the World,” in recognition of the

significant differences in suicidal behavior in different parts of the world.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and IASP are co-sponsors of

the event. WHO estimates 1 million people die by suicide every year,

representing a “global” mortality rate of 16 per 100,000, or one death

every 40 seconds.

A suicidal person urgently needs to see a doctor or mental health

professional. In an emergency, call the National Suicide Prevention

Lifeline, 1-800-273-TALK.

www.americanpsychotherapy.com

NEW MEMBERS

Giatue molorperat wisl digna

feum zzril

New

Members

dip exer ate feugiam

at.

DelitMarie

Ann

praesto

Arvoy

dolobore dio odit

alit nim quat. In eros dionsendre dolenit

Barbara

Helenluptatem

Bohman volorem

veliquat.

Iduismod

dio ea faciliquate venSarah

R. Cooper

dip el ulla feum nullum do ercin

henimCortes

ese facidui scilit vulput

David

vulla consectem iure dolor sed

mingV.exDiyankova

er at iriusci liquamcon

Irina

vel diam, quisi blam aliquipit

exerci et,

velestrud et adion velit

Calvin

L. Do

ulla corper sequat, commy nonsequi erW.

sisEmerick

exer alis nulput nim

Stephen

dolesto etuerci ea alisit, conse erciduntFavaro

lum am diam in eu feuLaura

giam nullam, sectet lum ing elit

iriure magnim

ing ex eugait, vel

Kathleen

R. Girman

del eliquisl delissit in ut laoreetuer am, velissenim

Michael

J. Griffin vulla at luptat.

Voloborper summy nim nulput

lobore Grubb

min ulputat ipit alisciNelson

dunt nullam eugiam iustrud dolent James

euguerHenderson

augait vent euismod

Jack

tatummo digniametue tat. Im incilis alis

nos nulluptat lute cortie

Edith

Hernandez-Putt

tet aliquam el et laor adigna corer

suscinHixenbaugh

vullamc onullaoreet, velis

Paula

acidunt alissit vullametue eum

aliquam

dip eugait aut praesti onJohn

F. Hockett

sequis dio do dolesting et, venim

alit praesseniam

dolorper iliquat.

Lora

Lee Hoffstetter

Iril doluptat. Ut iustrud modit

lortis endreK.consenim

aut vulla

Michaelene

Irwin

consequipisi tat. Vullan ut laorem

venisci

erate modiat, sim dolor

Judy

F. Kenny

iniat incidui tionsectet venim

vel dip eraesed

enibh ex er sequi

Michele

A. Langrick

ea core dit am quis dolore conum nostrud

Maston

Love dolorem nostrud tie

feum zzriliquam nosto endigna

facipitAnn

pratMcCarthy

nullandigna faci bla

Mary

faccum nullumsandre commodo

dolore conse

venisl enibh eum

Catherine

M. McClain

quam, vero odignissi.

(800) 592-1125

Welcome New Members and Fellows!

Os ad modoloborem irillamcorem zzrit

dolorti onsequam

Kenneth

M. atis

McEahern

il ex ex essequatem auguer aut la

facil essi.

Elena

V. Merenova

Bore con vel ipismodo dolore

consed B.

el eros

nibh et amet lobor

Brenda

Miller

ing et lorper sim volendrem exeros nosS. dolore

Pamela

Moore tet nullum vulla

atet dipisi ex eui blaortis non et,

qui bla facing

erciduis adipit velConstanza

Mossad

iquis dolor si.

Volesto

esequi blan venim duTiy-e

Q. Muhammond

ismod minibh euiscilisit at.

Uptatuero

dunt landre vullutMisty

S. Newcomb

patue eugiam exeraestrud mincilit voluptat

at, vulputp atuero et

Linda

M. Nichols

prat augait nulla feumsan drerit,

quat wis nullam

quatio ea conseNormand

A. Plante

qu issequisit nonulla alit nostrud

te facinci

enibh ea feu faccumsan

Sharon

Y. Powdrill

ea consendre magna feuguero

consedL.tie

tie feugait wismolor

Joseph

Rector

in vel ulla alismod magnis eriuscil ent

utpat

vel ullamco

Raul

Jaun

Rodriguez

Sora nsectet

la corem aliquis eugiam zzrilla

facincilisim

vulputpatio conulla

Sandra

A. Stava

feugait ing eum dolum dio esse

dipsusc

iliquat.

Lara

A. Strain

LayerNon vel er ipsumsan euis augait, volobor periurer sumsan

Sarah

Stukas verci blaor at. Ut ad

minit vendit praesto dolutpat.

San vel ullaore

dolessi.

Samantha

Swanson

Guer irit, qui blan venim vullum quam,

velesectem vel diat

Heather

A. Tietjen-Mooney

alisit nos at. Enim zzrit laorper

in eum

irit et augait ad eugiamSusan

Todd

commy nullam iriure moloreet

veliquisi.

Roland S. Trujillo

Vulput lorpero odipit adigna feugait N.

lummod

Ava

Weavermin er sit at. Odipis

acipit loreraesto corpero stionsequi et, Antoine

quisl ilit, quiscip isisi.

Achille

Gue feugait adiam zzrit aut irillam, D.

sis Atwood

nit iureetum numsandio

Joan

od eugiat nulputpat. Lutat nullam elesenisim

Marina

A. Breydovullamcon ut ut

aliqui bla feuisim iure tatie feu-

gue molor irit ullaor sit eniat.

Henibh

ut praessequis dolorBelton

D.elCaughman

tisci te facillum augait nullaortie

dit alit nisit

in ut lametue rosAnnette

Balsi Childs

tinibh elessequat aute tat. Lorem

quate dolor

susci

exer ing exer

Stephanie

Renee

Clafferty

susto delisl ip eraese mod deliquam, R.

veratet

ueraestrud tat lutShelley

DeReu

patummy num qm ad magna

aliquiscilit

euis

nulluptat alit ver

Richard

Dane

Holt

ipit lorer sis nos nulla amconse

modolore

eugait aut lorperos ex

Joseph

W. Nussbaumer

eugiatum dignism odigniam zzrilit utpatem

volenim zzrilla faJacqueline

M. Santoro

cilit adigna alit dolut lore minibh

eu facin

utat, vel in ver il ip eu

Maude

Silver

faci bla feugiam, conse vulpute

modit velenit,

quam nit nim euRichard

Frank Tavolacci

gue corper sisi er sustrud dolore

min euisVoigt

nosto dolobore feum del

Stephen

delessenis nulla facipsustie magna

aliquat, E.

quatum

nullummy nulla

Andrew

McGovern

augiam volor seniamet nostrud

et veliquat.

John

O’RourkeVeliqua mcommy

nim iure eraesecte feugait volendreet laZeno

conse

minis non hendre

Rosael

Santi

te te et ipsum nis do ex esto commy nulputpatis

numsandit ad

Elnour

Elnaiem Dafeeah

et atetue dolutpatio eu feumsan

henim nummy

Edward

Murray numsandre feu

faccummodio exer sum dolorper

sequamcoreet

Corinne

Libby il ut vullamc ommoloborem zzriliquis euipis ad

dolobore modoles tisciduisl ex

ea faccumm odigna

John W. Blanks

Martin J. Collen

Rosalina Sedillo Cruz

Ellen L. Flaum

David D. Flemmer

James Lynn Greenstone

Geraldine M. Gregg

Edwin W. Gunberg

Jack Haberman

Mary Susan Harris

Suella N. Helmholz

Sallie A. Hunt

Caroline Janoka-Garner

Lee D. Kassan

Lynda J. Katz

Carol A. Kryder

Jo Taylor Marshall

Marilyn Meberg

Marlin S. Potash

New fellows

Kevin Robert Powser

Barbara Kittinger Acho

Thomas E. Resburg

Donald W. Alexander

Nicholas A. Roes

Nan Beth Alt

Harry A. Royson

Fall 2010 ANNALS 13

CE ARTICLE: 1 CE credit

Conscience-Sensitive

Psychiatry,

Clinical

Applications:

Retrieval and Incorporation

of Life-Affirming Values In

a Personalized Suicidality

Management Plan

Abstract:

The authors’ intent is to introduce three psychotherapeutic techniques that they have found useful in helping suicidal youths surmount suicidal urges and build

life-affirming values. Together, the techniques honor

the functioning of the patient’s conscience. The article

provides an overview of empirical research identifyBy Matthew R. Galvin, MD; Barbara M. Stilwell, MD; ing conscience domains and stages; description of

and Jerry Fletcher, MD and instructions for utilizing diagnostic/therapeutic

exercises; and a case presentation with discussion.

14 ANNALS Fall 2010

www.americanpsychotherapy.com

Acknowledgement: This article is adapted for continuing education, with permission from the editor, from articles (Galvin,

Fletcher, & Stilwell, 2005; Stilwell, Galvin,

& Gaffney, 2006) appearing in Conscience

Works, electronically published at http://

shaw.medlib.iupui.edu/conscience. The

first cited article was a companion piece

prepared in anticipation of the publication: “Assessing the Meaning of Suicidal

Risk Behavior in Adolescents: Three

Exercises for clinicians” (Galvin, Fletcher,

& Stilwell, 2006).

Defining Conscience

and Its Domains

In 1982, authors B.S. and M.G. began using a semi-structured interview to assess

personal understanding of conscience in

children and adolescents who were free

of psychopathology, learning difficulties,

or major trauma. No a priori hypotheses

were established. Grounded in clinical experience, the investigation was empirical

and exploratory. Questions were chosen

because they were intuitively relevant to

mental development, health, disease, and

morality. These questions now comprise the

Stilwell Conscience Interview (SCI; Stilwell,

2003). Research interviews of 125 children

and adolescents were collected, read, and

rationally analyzed. Five domains of conscience were identified, each one related to

the moral aspects of a different category

of human experience: attachment, emotion, cognition, volition, and meaningmaking. Conceptualization of conscience

was considered to be the anchor domain.

Contributory domains of conscience that

correlated with the anchor domain were

named: moralization of attachment, moralemotional responsiveness, moral valuation,

and moral volition.

Five stages were identified within each

domain for part of the life span, ages 5

through 17. Standard research methodology established inter-rater reliability

and construct validity for the domains

and stages. The results were published

one domain at a time (Stilwell & Galvin,

1985; Stilwell, Galvin, & Kopta, 1991;

Stilwell et al., 1994, 1996, 1997, 1998).

The following paragraphs review the five

domains, while Tables 1–5, found on

page 16, summarize the developmental

highlights of the domains within each of

the five stages.

(800) 592-1125

A General Definition

of Conscience

Metaphorically speaking, conscience is the

moral heart of the personality. How does

this heart come to be? Beginning with a

biologically prepared impulse to sort experiences into good and bad categories in

early childhood (Kagan, 1998), conscience

develops as an intra-psychic structure that

stores the “oughtness” messages from life’s

lessons about good and bad, right and

wrong. Within most individuals, understanding of goodness and badness, the objects of conscience, grows in increments

of organized meaning under the guidance

of moral nurturance, experience, and development. Goodness is first experienced

through the satisfaction of needs. Bedrock

values, the most basic forms to apprehend

goodness, are engendered in the process of

having needs both met and unmet. Thus,

an infant’s need for human attachment engenders a value for connectedness; the need

for emotional regulation engenders a value

for harmony; the need for goodness itself

engenders the logical structuring of valueladen experiences (value-sensitive rule making); the need to act and restrain engenders

the value of autonomous will; and the need

to coordinate experience into a meaningful

whole generates the synthesizing value of

moral meaning making. These bedrock values guide life’s first expectations and obligations. As domains of experience are further

moralized through nurturance, development, and the challenge of making moral

sense of life’s experiences, value-connected

expectations and obligations become increasingly differentiated and integrated.

Moralization of Attachment

The personhood of conscience evolves from

empathic responsiveness within parentchild dyads as mutual demands and expectations become connected to the desire to

please and to be pleased. As the child conforms to parental expectations (and the parent responds to the child’s needs), security

within the relationship is enhanced; nonconformity and unmet needs stress the relationship. The intimate association of secure

attachment and empathy with the experience that some things ought to be (or ought

not to be) becomes the interpersonal core

of the conscience mental representation.

We term this the security-empathy-oughtness

bond (Stilwell et al., 1997).

This article is approved by the following for continuing education credit:

The American Psychotherapy Association provides this

continuing education credit for Diplomates and certified members, who we recommend obtain 15 CEs per

year to maintain their status.

After studying this article, participants should be

better able to do the following:

1. Identify five domains of conscience

2. Identify five stages of conscience

3. Utilize a Suicide Narrative to help both patient and

therapist understand motivations and resistance

toward suicide

4. Utilize two conscience-sensitive exercises, not only

to build resistance to suicide, but to strengthen lifeaffirming values: a) the Moralized Genogram and b)

the Value Matrix

5. Help a patient construct a personalized Suicidality

Management Plan

KEY WORDS: Conscience, conscience-sensitive

interactions, life-affirming values,

Suicidality Management Plan

TARGET AUDIENCE: Mental health professionals

engaged in psychotherapy with suicidal youths

PROGRAM LEVEL: Intermediate

DISCLOSURES: The authors have nothing to disclose

PREREQUISITES: none

Moral-Emotional

Responsiveness

The emotional power of conscience evolves

as parental demands and expectations become values around which the child’s emotions are regulated (Stilwell et al., 1994).

The content of what it means to be good

(pleasing behaviors) takes form in relationship to feeling good (feeling pleased

or satisfied). An am good / feel good state of

moral-emotional equilibrium motivates

the developing child to inhibit prohibited

behaviors and to engage in pleasing, prosocial behaviors. Feelings of goodness or

badness are tied to the body’s physiological

processes, which, in turn, signal the person

when moral-emotional equilibrium is disturbed by behavior the individual deems to

be bad or wrong. Reparation and healing

processes (e.g. forgiveness) are then learned

and practiced to restore moral-emotional

equilibrium.

Moral Valuation

The value-processing power of conscience

is initiated when the child begins to use

cognitive skills to actively evaluate parental

demands and expectations in the face of her

own needs and desires. As the child moves

into the larger community, values governing

three types of relationships become important: values governing her relationship to

authority, values governing her relationship

Fall 2010 ANNALS 15

C l i n i c a l App l i c at i o n s

Table 1: The External Stage Conscience

Domains

External Stage (6 and under)

Moralization of Attachment

Parent-child empathic responsiveness generates bi-directional sense of “oughtness.”

Moral-emotional Responsiveness

Positive emotions become linked to sense of goodness.

Moral Valuation

Moral expectations emerge from daily routines.

Moral volition

Willpower is directed toward commitment to restraint.

Conceptualization

The conscience is perceived in terms of action scenarios with elders in which right and wrong behaviors are punished or praised.

Table 2: The Brain-Heart Stage Conscience

Domains

Brain-Heart Stage (7–11)

Moralization of Attachment

Disciplinary practices shape moral tone of parent-child relationship.

Moral-emotional Responsiveness

Anticipation of negative emotional response to wrongdoing emerges; rudimentary processes of reparation and healing emerge.

Moral Valuation

Some moral rules are constructed from consequential learning; others are internalized directly as mandates of elders.

Moral volition

Willpower is directed toward mastery of skills and demonstrating sufficiency in the pursuit of goodness.

Conceptualization

The conscience is perceived as a storage site for moral rules.

Table 3: The Personified Stage Conscience

Domains

Personified Stage (12–13)

Moralization of Attachment

An internalized and often “anthropomorphized” conscience supplements the moral authority of elders.

Moral-emotional Responsiveness

Initiative characterizes the pursuit of virtues and undertaking of reparative actions after wrongdoing.

Moral Valuation

Rules are interpreted in light of the dynamics of maintaining good relationships.

Moral volition

Willpower is directed toward the pursuit of specific virtues.

Conceptualization

The conscience is perceived as a “someone” for dialogue requarding moral issues.

Table 4: The Confused Stage Conscience

Domains

Confused Stage (14–15)

Moralization of Attachment

Independence from parental moral authority is facilitated by attraction to idols and ideals in the culture.

Moral-emotional Responsiveness

Emotional reactivity over conflicts of loyalty intensifies.

Moral Valuation

Conflicts over moral issues between self and authority, self and peers, and self with self prompt “weighty” moral processing.

Moral volition

Willpower is directed toward idealism.

Conceptualization

The conscience is perceived as struggling to integrate various sources of moral authority.

Table 5: The Integrating Stage Conscience

Domains

Integrating Stage (16+)

Moralization of Attachment

Image of becoming a moral authority for progeny emerges.

Moral-emotional Responsiveness

Emotional comfort with making individualized moral choices emerges.

Moral Valuation

Being true to oneself becomes a dominant value.

Moral volition

Willpower is directed toward “personal best” moral choices.

Conceptualization

The conscience is perceived as an entity that incorporates the concept of good within evil and evil within good.

16 ANNALS Fall 2010

www.americanpsychotherapy.com

C l i n i c a l App l i c at i o n s

to peers, and values governing obligations to

herself. It is within this valuational triangle

that moral dilemmas arise and must be resolved. All cognitive processes are activated:

language—how to frame moral choices and

challenges; memory—what precedents are

applicable; reasoning—what logic can be

applied; moral judgment—what cumulative

valuation will guide action. Uncertainty,

fallibility, and bad choices foster moral justifications—psychological defense mechanisms centered on moral issues. Through

the valuation process, the growing child

gradually learns about moral complexity

(Stilwell et al., 1996).

Moral Volition

The willpower of conscience evolves as the

child’s capacity for action and restraint, attention, and effort are moralized in the process of exercising autonomous will (Stilwell

et al., 1998). Living involves both willed

and unwilled behavior. Evolutionarily prepared dual abilities to act before thinking

and think before acting (LeDoux, 1996;

Libet, Freeman, & Sutherland, 1999) lead

to behaviors as diverse as life-saving actions or impulsive, self-defeating ones.

Even when humans think before acting,

pre-conscious factors—biological drives,

emotional arousal, relationship loyalties—

may combine with situational cues and demands to mar or enhance moral choice. As

the child grows in ability to use consequential feedback and deliberate self-assessment,

she grows in ability to be in charge of her

moral actions.

Conceptualization of

Conscience

The power of conscience as a whole evolves

as the child synthesizes moral meaning from

the domains of moral attachment, moralemotional responsiveness, moral valuation,

and moral volition. Conscience is the moral

organizer in each person’s autobiographical

journey, a moral governor at the heart of

the personality. Children have great facility

to both draw and define their conscience

when the language of inquiry is adjusted

to their cognitive abilities. Five discrete

stages of synthesis can be identified before

age 18 (Stilwell & Galvin, 1985; Stilwell

et al., 1991).

Case Illustration: Regina

In accordance with HIPAA regulations,

all identifying information, including the

location of the subject of this report and

(800) 592-1125

dates of admission to other facilities, has

been expunged from the record. To ensure

fidelity to the case, all dates will be indicated in reference to the date of the admission; for example, “one week prior to admission (PTA).”

Twelve-year-old Regina presented to the

emergency room in her local hospital after

her school counselor discovered a suicide

note in her binder. Upon her arrival at the

access center to the psychiatric hospital

about 50 miles away, Regina told how she

had composed the note while frustrated

about her homework and upset about an

episode of her stepfather’s anger dyscontrol.

When a child’s basic

needs are poorly met in

the areas of attachment

and emotion and when

she is confused by the

values of mistreating

adults and helpless to

take action, her own

conscience can become

severely distressed,

resulting in “demoralization” and loss

of life-affirming values.

She denied any intent to commit suicide,

and there was no history of previous suicide

attempts. However, her mother indicated

that Regina had talked about suicide during the eight months PTA. She was subject

to reduced total sleep time but denied difficulties in concentration and experienced

no diminution in appetite. She had briefly

engaged in treatment at a community mental health center for “depression and behavior.” No medications were prescribed. Her

personal history was negative for alcohol

and substance abuse. She denied any current or past sexual activity. She initially de-

nied any maltreatment experiences in the

form of physical abuse, sexual abuse, and

neglect, but did indicate exposure to domestic violence. The mental status examination conducted by the access center worker

described her as disheveled, with holes in

the elbows of her knitted shirt, tearful in

presentation, avoidant of eye contact, withdrawn, and depressed in mood. The case

was staffed by telephone. Regina was admitted by the child adolescent psychiatrist

on call. Suicide precautions were ordered.

The first clinical encounter with her assigned psychiatrist occurred the next morning. Regina was highly distressed about

remaining in the hospital. She urgently repeated several times that she did not mean

to write the suicide note. She spontaneously denied any intention of ever making

herself die. Regina became more communicative through her tears, which she ascribed to being away from “my Mommy”

for the first time. Her separation anxiety

was probably compounded by having to

undergo treatment for head lice, including temporary isolation.

The psychiatrist’s evaluation mostly confirmed the findings of the access center

worker in the mental status domains of appearance, attitude and behavior, affect and

mood, sensorium as well as judgment and

insight. In contrast, while Regina’s responses

to questions posed in the psychiatric evaluation were pertinent, they were also concrete. Her use of vocabulary and grammatical structures indicated a less-than-average

intellectual functioning and/or the presence

of specific learning disabilities.

When a child’s basic needs are poorly

met in the areas of attachment and emotion, and when she is confused by the

values of mistreating adults and is helpless to take action, her own conscience

can become severely distressed, resulting in “de-moralization” and loss of lifeaffirming values. Accordingly, Regina’s

psychiatric evaluation was conducted in

a manner sensitive to conscience functioning, via innovations that conform

to the American Academy of Child and

Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Practice

Parameters for the Psychiatric Assessment of

Children and Adolescents (AACAP, 1997),

namely: (a) adapting for clinical use core

questions first developed in research and

(b) utilizing interview techniques designed

to elicit information about conscience

functioning with respect to presenting

problems (Stilwell et al., 2006).

Fall 2010 ANNALS 17

C l i n i c a l App l i c at i o n s

5

5

Legend

Legend

19

19

when she was 3 years old, three of her brothers

were removed from the home in a Western state

and each spent time in juvenile detention prior

Residing in Regina’s home

Residing in Regina’s home

Regina’s Conscience

The initial conscience inquiry was adapted

from the SCI (freely available at Conscience

Works). Conscience Conceptualization: Regina

indicated she was sometimes aware of a part

of herself that helped her figure out right

versus wrong. She described this part of

herself as quite active. Moral Emotional

Responsiveness: Regina indicated she generally

experienced herself as a good person. When

engaged in what she considered to be rightdoing or good deeds, she said she was apt to

become excited but did not somatically localize the corresponding feelings or sensations

(as many persons do). In response to what

she considered to be engagement in wrongdoing, she said she was apt to feel both sad

and mad. She did not discern an appreciable

change in her moral emotional responses if

either her right-doing or her wrongdoing

remained unknown to others, although she

18 ANNALS Fall 2010

9

9

among Regina’s full sibship. Regina reported that

Bipolar Disorder, NOS

Bipolar Disorder, NOS

Moral Attachment Figure

Moral Attachment Figure

16

16

Regina’s mother identified only the nine year old

Perpetrator Child Sexual Abuse

Perpetrator Child Sexual Abuse

Relationship with positive valence

Relationship with positive valence

17

17

12

12

Alcohol, substances, violence

Alcohol, substances, violence

Relationship with negative valence

Relationship with negative valence

18

18

to placement because of threats they made to

kill their mother.

Figure 1: Regina’s MORALIZED GENOGRAM

conveyed that she would “tell on herself” in

any case. Moralized Attachment: She identified her mother and her maternal grandmother as those persons who cared most

whether she led a good life and did the right

things (i.e. principal moral attachment figures). Moral Valuation: Whereas most children identify several “rules of conscience,”

Regina identified only one: “Don’t drink

alcohol and stuff.” Moral Volition: Initially,

Regina found it difficult to discuss any successful experiences she had had in either resisting urges to engage in wrongdoing or

overcoming her resistance to engagement

in right-doing.

She acknowledged the internalization of a

moral presence; described that her emotions

rose and fell in response to pleasing or failing to please that presence (as well as people outside of herself ); identified one “rule

of conscience”; and was uncertain about

having any moral willpower. Evaluating

Regina’s responses to a conscience-sensitive

inquiry in the light of Tables 1–5, we would

judge that her conscience development has

barely reached Stage II.

Regina’s case was chosen for this very reason: to illustrate the approximate minimal,

rather than optimal, characteristics needed

for a patient to be engaged in the diagnostic/therapeutic exercises we refer to as conscience-sensitive interactions.

These conscience-sensitive interactions

have been used with older school-age children and adolescents, both male and female, with intellectual capacities low average or better in settings such as acute

inpatient, intensive outpatient, and outpatient. Aside from age and intellectual capacity, consideration of stage of conscience

development is important. Considerations

of a person’s stage of conscience development and particular strengths and weaknesses in conscience functioning lay the

foundation for conscience-sensitive interactions. With rare exception, initial conscience inquiries adapted from the SCI are

used as part of psychiatric evaluation in

the first author’s practice (which includes

frequent work with developmentally disabled youth). However, we have learned

from experience that a person must have

www.americanpsychotherapy.com

C l i n i c a l App l i c at i o n s

achieved at least Stage II in a conscience

evaluation to benefit from the therapeutic procedures that follow. Different techniques are necessary for individuals with

less than Stage II development.

With the initial conscience inquiry, a

question emerges. Is the person primarily

delayed in conscience development, or has

the person temporarily lost her purchase

and slipped on this particular developmental trajectory by becoming de-moralized in

one or more conscience domains? Answers

to questions of this sort will make a difference in terms of the therapeutic project. If

primarily delay is discerned, then the therapist, the treatment team, and responsible

family members may be obliged to provide

“scaffolding” to support the person of conscience until she can advance to the next developmental stage. If a primary condition of

de-moralization is discerned, support is more

likely to be directed to dealing with pathological interferences, which stand in the way

of re-moralization, and more firmly securing

prior developmental accomplishments.

Regina’s Case Continued:

Conscience Sensitive

Interactions —The

Moralized Genogram

In subsequent sessions with her psychiatrist,

Regina was able to elaborate on the nature

of the domestic violence to which she had

been exposed and that fueled her worries

of harm befalling her mother while absent.

She also disclosed having experienced direct

physical abuse in the form of being choked

by her stepfather during a period of intoxication. In a later session, she was engaged

in constructing a Moralized Genogram

(see Figure 1).

The project of the genogram is mutually

undertaken by the therapist and patient.

The therapist teaches the symbols for the

genogram, depicting biological connections

in black and emotional connections and

disconnections in red. Moralized attachments and detachments are layered upon

the more familiar biological and emotional

connections/disconnections by filling in or

circling the symbols with green.

While constructing the Moralized

Genogram, Regina echoed family psychiatric history her mother had provided independently at admission: her mother, her

maternal grandmother, and her sibling (also

diagnosed with ADHD) being subject to bipolar disorder, not otherwise specified. She

conveyed her impression that her biological

(800) 592-1125

father had, like her stepfather, been subject

to alcoholism and was prone to violence. She

knew of a paternal uncle who had been subject to substance abuse and was incarcerated

for child molestation. She identified family

members her mother had not: three brothers, placed with another family out of state,

each in later adolescence and each having

spent time in corrections for threatening the

mother. She also provided the additional history that she had been taken from her mother at age 6 for three months due to neglect.

Those persons represented as caring about

her moral well-being were her mother, both

maternal grandparents, and a 19-year-old

brother living outside the home. She represented a highly conflicted relationship with

her stepfather and expressed the wish that

her mother would not be so afraid of him so

she could compel him to leave their home.

In Regina’s case, the Moralized Genogram

opened up much more psychosocial information and abuse history. The straight and

jagged lines depicting emotional connections and disconnections improved mutual

understanding of her suicidal motivation.

In the depiction, maintaining emotional

connectedness with her mother emerged as

a powerful motivator for Regina, possessing

life-sustaining value. The colorful marking

of principal moral attachment figures was

the first glimmer that the life-affirming value moral connectedness might also operate as

a motivator in her life. This information,

made visible by depiction, set the stage for

strengthening Regina’s consequential thinking in light of her values. The psychiatrist

was prepared to cautiously introduce the

next conscience-sensitive interaction and

accompany Regina on her Suicide Walk.

The Suicide Walk

Regina was asked to conduct herself through

a Suicide Walk. This clinical device was introduced to youth psychiatric inpatients

about 15 years ago by author J.F. The instruction given to the patient is:

Write a story in first person as if you

actually killed yourself. Write about

what led up to your suicide, how you

felt, why you did it, and how you did

it. Write about your funeral, who is

there, what they are saying, and what

they are feeling. Write about how your

suicide affects your family and friends

and how they feel. Then write about

life afterwards for your family and

friends. (This assignment may take

several pages to write.)

This was Regina’s written response, which

was completed on hospital day #2:

I led up was very frusted one day

I a enough I felt like killing myself.

I got on the bus. Then after I did I got

off at my bustop. I walking to home from

my bustop and there was a car going

really fast. I ranned out in front of it.

The next day they had my funrel going on. A lot of people was there like my

mom, brother, sister, grandmal, grandpal, freinds. I don’t know exaltey they

were saying. But all I could hear how my

sayed I wish hadn’t done that. My family

was destroyed. My friend was destroyed.

My family hearts was broke. My friends

hearts were broke too. That’s my story.

In this manner,

the patient develops

an appreciation of how

biological conditions

can affect her as a

person of conscience.

The assignment of this therapeutic task

may elicit resistance from many patients. In

some cases the resistance arises in patients

who, after the rigors of medical stabilization in the emergency room, exposure to

distress among family members, and acute

psychiatric hospitalization, have enjoyed a

“flight into mental health” and insist that

the suicidal behavior was anomalous, guaranteed never to occur again. In other cases, resistance issues from the extremes of

de-moralization. In still other cases, the

exercise may be undertaken with an excess of enthusiasm for an opportunity to

demonstrate a flair for the dramatic or to

engage in compensatory grandiosity. From

the standpoint of the therapist, it enriches

psychodynamic understanding of the patient and provides a view on the nature of

the patient’s suicide planning and deliberation, or lack thereof. Once undertaken, it

often assists the patient in recapitulating her

state of mind that resulted in suicidality. It

prompts, with varying degrees of success,

self-examination resulting in clearer identification of the strongest suicidal motives.

It prompts consequential thinking. It also

Fall 2010 ANNALS 19

C l i n i c a l App l i c at i o n s

becomes the springboard for an exercise in

moral imagination.

In the next clinical encounter with her

psychiatrist, Regina was instructed to read

aloud her Suicide Walk. As is often the

case with patients, she attempted to avoid

the reading by handing over her narrative.

Upon redirection, she began to read aloud

but at a rapid pace. She was instructed to

begin again and slow down. The rationale

shared with her was to have her listen carefully, together with her psychiatrist, to what

she was reading. As a practical matter, the

read-through also clarified what the patient

attempted to communicate in writing but

was hindered because of her grammatical

and spelling weaknesses. At the conclusion

of the read-through, the inquiry was made

to her: “How do you react to what you’ve

written and read just now?”

Regina’s Case Continued

At the point of admission, Regina had indicated the strongest suicidal motive she

would ever experience would be the loss of

her mother. She had been unable to adduce

any life-affirming or even a life-sustaining

value. After therapeutic work in the form of

the Suicide Walk and Moralized Genogram,

she was able to retrieve connectedness as a

life-sustaining value. However, her connectedness was not yet fully moralized; indeed, she primarily evinced fear of separation: “I would be away from my Mommy

if I killed myself.”

Fears that counteract suicidality may take

other forms. Fear of pain or of the process

of dying or of eternal punishment in accordance with religious beliefs will sometimes

be adduced. In such cases, we recommend

exploring further. To conduct the exploration, another conscience-sensitive clinical

device may be employed.

The Value Matrix

The foursquare organizational schema (see

Figure 2) is the graphic outcome of a dynamic process in which the therapist facilitates the patient’s self-examination of

the valuational contents embedded in her

conscience. We will first provide an operational description of the value matrix. Then

a dialogue distilled from many clinical encounters will be provided before describing

the outcome with Regina.

Operationally defined, for any x, the inquiry takes the form: “If you (a person)

went along with x, it would be because

——— (fill in the blank).”

The form in which x is put is a matter

for the therapist’s discernment. The therapist may discern that the patient continues to harbor suicidality and so x may be

given forms like “DO make myself die”