Practical Guidelines for the Fabrication of Duplex Stainless Steel

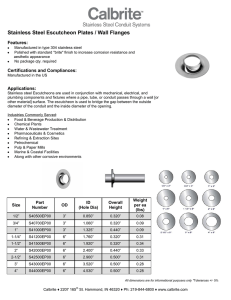

advertisement