Questionnaire design and analysing the data using SPSS page 1

advertisement

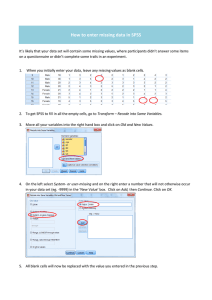

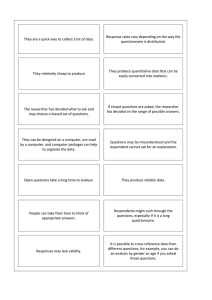

Questionnaire design and analysing the data using SPSS page 1 Questionnaire design. For each decision you make when designing a questionnaire there is likely to be a list of points for and against just as there is for deciding on a questionnaire as the data gathering vehicle in the first place. Before designing the questionnaire the initial driver for its design has to be the research question, what are you trying to find out. After that is established you can address the issues of how best to do it. An early decision will be to choose the method that your survey will be administered by, i.e. how it will you inflict it on your subjects. There are typically two underlying methods for conducting your survey; self-administered and interviewer administered. A self-administered survey is more adaptable in some respects, it can be written e.g. a paper questionnaire or sent by mail, email, or conducted electronically on the internet. Surveys administered by an interviewer can be done in person or over the phone, with the interviewer recording results on paper or directly onto a PC. Deciding on which is the best for you will depend upon your question and the target population. For example, if questions are personal then self-administered surveys can be a good choice. Self-administered surveys reduce the chance of bias sneaking in via the interviewer but at the expense of having the interviewer available to explain the questions. The hints and tips below about questionnaire design draw heavily on two excellent resources. SPSS Survey Tips, SPSS Inc (2008) and Guide to the Design of Questionnaires, The University of Leeds (1996). The format of your questions will affect the answers; Keep your questions short, less than twenty five words if possible. Keep questions understandable make sure the subject understands the terms used and importantly how the format of the questionnaire works (an already filled in example is often useful for this). Don't use “double negatives,” they can be confusing. Choose appropriate question formats so they are understandable to the person answering and that enable you to analyse the resultant data. Some questions can be easily answered with a simple single answer (e.g. do you smoke (y/n); what gender are you? (m/f), but others may require multiple choices a scale or, perhaps even a grid. Do make sure you know how to analyse the data you get, if you can't analyse the resulting data there was little point in collecting it. A research proposal should address analysis, a simple sentence "data will be analysed using SPSS" may pass the buck to SPSS but won't help much when you refer back to your plan. You should have an eye on the analysis when designing the questionnaire. Checking this is feasible should be part of the piloting; this will check that the data are arrangeable in the formats needed for analysis and that you have the resources to do it. Questionnaire design and analysing the data using SPSS page 2 You might include open ended questions in the questionnaire, do though be aware that they will be "tainted" by the context of being in with strictly quantitative questions. The pilot is a good time to use more open questions to check there are sufficient options on multi choice answers and that there is sufficient discrimination in the questions, so not all the answers are the same when there is likely to be a range of views/responses. Ambiguous questions. Check for ambiguity in your questions, make sure what you're asking is obvious. Ambiguous questions not only yield no useful data but can frustrate the respondent and encourage them to give up! Avoid asking two questions at once. For example, “Are you happy with the amount and timeliness of feedback you receive from your tutors?” Analyzing the responses to such a question would be made practically impossible because you won’t be able to tell which part of the question the respondent was answering. Leading Questions. Leading questions will bias the results, this will reduce objectivity and hence the value of the research. What is your opinion of the price of cinema admission? Very expensive - Expensive - Fair - Cheap - Very cheap Cinema tickets are too expensive: Strongly agree - Agree - Disagree - Strongly disagree You'll never get it 100% right, the question above has a rather subjective, "Fair" is open to interpretation - we might have used "About right" - it is hard to not be ambiguous and leave no room for interpretation. Notice on the second of the two versions above that I didn't put a middle "neutral" value in. There is room for debate on this subject, not providing a fence for folk to sit on might encourage people to vote one way or another - but if a respondent has truly a neutral view they might choose to not fill in that question and so there is a bias in the data. The second version could be complimented by the same question asked in the opposite way, e.g. "Cinema tickets are not too expensive". We would expect to get a good level of negative correlation between the two versions, if so, this would indicate internal validity, if not it might indicate people were just clicking the same response to all the questions. Layout and question types. Be absolutely unambiguous about how the subject should fill in the question, e.g. Do you hold a full driving licence? (Please circle the correct choice) YES NO Questionnaire design and analysing the data using SPSS page 3 or probably better; Do you hold a full driving licence? YES…□ NO…□ Use tick boxes rather than just blank space to solicit the subjects' choice, line them up with centred tabs, use, for example, the "Insert symbol" feature in MS Word to insert a box character. MS Word can offer more tricks, the "Forms" feature offers you a way to make the document interactive, useful if you intend to deliver and receive forms by email. Strongly agree Agree Ambivalent Disagree Strongly disagree □ □ □ □ □ If your word processor doesn't offer box characters use brackets [ ]. An attractive survey form will be more appealing to the respondent and encourage a better quality of data. You can make a paper survey more inviting by enhancing readability, including white space to avoid large uninviting blocks of text, this increases readability. A very busy or cluttered questionnaire can confuse respondents. Colour might help in some cases, for example to delineate between sections. Avoid using lots of different fonts, typically stick with Arial and use bold for headings, using lots of different text styles can make the document look scrappy and confuse the respondent. Surveys conducted online have a greater variety of objects available to spice up the presentation but do make sure they don't detract from the basic data gathering agenda. The issue here is about your confidence in setting an online survey up and the issue of bias - it wouldn't be very good, for example, at assessing the level of computer confidence among a target group! Try it out! Run a Pilot. When you have created the ultimate questionnaire try it out. It is very unlikely to be right first time! Don't just pilot the survey but carry that data through to analysis to check that your analysis plan is capable of offering the results you are aiming for. Solicit comments from your pilot group, friends might be shy of being critical, make sure they feel it is OK to note the shortcomings. How long should a questionnaire be? How long is a piece of string? - there is no definite rule but as guidance the amount of time people will happily take in filling it in will depend on their interest or "stake" in it. I f you want to press me for a guide then twenty Likert type questions is probably Questionnaire design and analysing the data using SPSS page 4 OK but forty is probably too many! It does depend partly on the target group. The real issue is how long does it take to fill it in? Another good reason to properly pilot it! What kind of questions should I use? They should fit two criteria; they should furnish the data required and they should give you data that can be arranged into a format you can analyse. There are a couple of examples above, the Likert scale question and the yes/no question. It is vital that you consider how you will analyse the resultant data when adopting a question style. Yes/No and Likert questions are great, the Yes/No question yields categorical (Nominal) data. More specifically Yes/No or Male/Female are a specific type of category called a dichotomous category, one that can take just one of two values. You might meet others, e.g. How did you get to work today (tick one only); Walk Car Bus Train Other □ □ □ □ □ The "Other" category is useful - if on the pilot you get a large contingent of "Other" then you might analyse these and introduce an extra named category. Compare the question above to this one… What transport do you use to travel to work (tick all that apply); Walk Car Bus Train Other □ □ □ □ □ This second version lets the respondent tick all the boxes they use or have used. The resulting data is more complex to analyse. It does have an advantage in that it lets us gauge the range of transport used, it doesn't though give us any discrimination between the popularity of the various modes of transport, if someone only used a car once this year they might sensibly still tick "Car" and "Bus" even if all their other journeys to work were buy bus. Questionnaire design and analysing the data using SPSS page 5 Sorting and ordering questions. Sorting and ordering questions tend to increase the complexity of analysis. Rank the types of transport you use for travel to work, 1 = use most often, 5 = use least often; Walk Car Bus Train Other □ □ □ □ □ The data from this question will be richer than that from the earlier examples but as a consequence much more complex to analyse! The question you must address is "am I making a rod for my own back?" i.e. don't make a questionnaire that you can't analyse, you have to get the results out of the data when it is all gathered! Can I include open ended questions? Many questionnaires place open-ended questions at the end, this makes analysis easier but do remember that these "qualitative" questions will be seen in the light of the quantitative ones that precede them - this is generally an issue when mixing qualitative and quantitative methodologies in the same questionnaire. The questions in the questionnaire might colour the thoughts of the respondent and influence their answers to the open questions. Questionnaire design and analysing the data using SPSS page 6 So how do I analyse it then? We can use a mixture of descriptive statistics and graphs and some nonparametric inferential statistics. Unlike examples when we have real measurements when we might be unsure about the wisdom of applying parametric methods, it is reasonable to apply nonparametric methods to the data collected from most questionnaires if the responses can be described as scores rather than true measurements. There is inevitable debate on this in the statistical community but I would suggest that you start from the basis of applying nonparametric methods rather than the other way round. The data in the file Students data 2001.sav was gathered as part of a large project looking at the IT skills of new students. The data in the file are only a part of the data gathered, we have just kept a few sample question, but for these questions all the gathered data are in the file. The part of the questionnaire that gathered the data is re-synthesised below, it is worth noting that when the data were gathered the university was split into schools, it has since been reorganised into a smaller number of faculties. Have a look at the questionnaire and check that you can see how it is related to the data file. When you analyse your own data you will have to translate the data from your questionnaires to a file on the computer. There are some general hints that might help; • Each of your subjects/respondents will usually have one row in the data sheet. • Each question will typically have one column (i.e. it will take up one variable). • Responses will be stored as numbers (e.g. 1 to 5 for lickert scales) and the “Value Labels” will ascribe text labels to the numbers. • If you have used Ranking or ordering questions then each option will take up a variable, this will also be the case when the respondent is asked to “tick all that apply” We can use the Students data 2001.sav data file to have a go at some methods that might be useful… First let’s look at the file, there are 2614 entries in the file from first year students in the year 2001. Each entry takes up one row in the data sheet, this is usual for SPSS data, so in this file there are 2614 rows. Depending upon the view of the data you have you will either see lists of words or numbers. You can toggle between the two views by choosing “Value Labels” from the “View” menu. Questionnaire design and analysing the data using SPSS page 7 What school are you studying in? EDS Education □ HSC Health and Social Care □ SCI Science and Mathematics □ SED Environment and Development □ SLM Sport and Leisure Management □ CMS Computing and Management Sciences □ SSL Social Science and Law □ ENG Engineering □ SCS Cultural Studies □ What is your Gender? Male Female □ □ How old are you? 18-24 25-30 31-40 41-50 51-60 60+ □ □ □ □ □ □ How do you rate your own basic computer use? Below basic level □ Basic □ Competent □ How do you rate your ability to use statistics software? (e.g. Minitab, SPSS) not competent competent □ □ Questionnaire design and analysing the data using SPSS page 8 To set these meanings behind the numbers you use the “Variable View” tab at the bottom of the screen. Click the “Values” column for the variable you want to create or alter labels for and then hit the small button that appears in the column, the “Value Labels” dialog box should appear. This is where you can type in each unique value and the corresponding text label. After typing in each pair click “Add” to add it to the list. You can also change and remove labels. Spend some time on your data to get the labels correct, these labels will appear on your graphs and other output it is best to keep them reasonably short. SPSS will not automatically check the spelling of your labels. Starting to look at the data. It only takes SPSS a few seconds to do what might take all evening to do with questionnaires spread all over the dining room floor! So we can afford to play with the data to tease out meaning from it. In our large sample of 2614 subjects we might want to do some basic demographic analysis, this is a useful preface to recording our results in any research project, it is where we tell the reader about the subjects who our results are based on. To analyse for simple percentages we can use the “Frequencies” command (choose Analyse then Descriptive Statistics, Frequencies). In this example I've put the Gender variable across to the variables box, have a go and hit the OK button. You might notice that the OK button is in a different place in this later version of SPSS, this change happened between versions 15 and 16, the functionality however is not altered. The output below is the resulting frequency table, it tells us that out of a total of 2614 respondents 1244 are female, 1342 are male and the data on gender is missing for 28. This accounts for all our 2614 subjects. The percentage columns are of interest, the “Valid Percent” is calculated after the missing values are ignored. The “Cumulative Percent” isn't relevant for this analysis, but if we had data that were for example, an ordinal satisfaction scale, then this might be useful (we might be making statements like “76% of responders were not dissatisfied”). It can sometimes be helpful to think of the kind of statements that you might make about the results, this can help guide your analysis. Questionnaire design and analysing the data using SPSS page 9 Which column would you use? The valid percent leads us to statements like “51.9% of those responding to the question were male”, it would be sensible to offer the level of reply (in this case 98.9%) or (and I like this approach) put the results in a table, the actual figures can be put in brackets next to the percentages. A column can be made for the response rate for each question if you like. We could similarly look at the age profile of our respondents. Try this now. From the cumulative percentage column we can see that over 90% of respondents (91%) are 30 or younger. More importantly it gives us a good breakdown of the responses. Looking at two variables at once, for example; are the age profiles similar within the genders? This is where crosstabulations come in useful. To create a crosstabulation pick "Crosstabs" from the Analyse, Descriptive Statistics menu, I've put the "Age" variable in the rows box and "Gender" in the columns. The output shows us the number of people in each age group but this time there is a column for each gender as well as a total column that should have the same figures in as the earlier frequency table we created unless age or gender data are missing. This simple cross tabulation allows us to see that although there are slightly less females overall there are considerably more in the 31-40 and 41-50 age groups than there are males in those age ranges. We can get a better view of these results that will help us compare the gender/age relationship if we calculate percentages. We can ask SPSS to calculate the percentage of each gender in each age group. To do this go back to the Crosstabulation dialog box (Analyse, Descriptive stats, Crosstabs) and click the “Cells” button. Then click to add column percentages. The resulting table looks more complex because it gives both the raw number of respondents in each combination of gender and age group. You can if you want show percentages only by switching off the “Observed Counts” in the cells dialog. Questionnaire design and analysing the data using SPSS page 10 In a results section you wouldn’t simply copy and paste the output tables into the document, you might create a table including the output but in a more readable format, for example; Crosstabulation of Age and Gender showing percentages within each gender. Make sure the title of your table clearly states what it intends to illustrate. Age In this case we can see that larger percentages of females than males over 30 are becoming students. Gender Male Female 18-24 1159 (88.50%) 989 (81.70%) 25-30 73 (5.60%) 75 (6.20%) 31-40 60 (4.60%) 98 (8.10%) 41-50 15 (1.10%) 46 (3.80%) 51-60 2 (0.20%) 3 (0.20%) will use for this is the Chi-square statistic. We would have been surprised though if all the percentages were the same, some variability due to chance is inevitable. We can look to inferential statistics to tell us how likely we are to see such a difference in the percentages by chance. The statistic we Chi-Square Tests Asymp. Sig. The “Statistics” button Value df (2-sided) on the Crosstabs dialog Pearson Chi-Square 34.816a 4 .000 lets you request the Chi-square statistics. Likelihood Ratio 35.628 4 .000 They come in various Linear-by-Linear 32.798 1 .000 types, in our example Association here we don’t need to N of Valid Cases 2520 worry about which to a. 2 cells (20.0%) have expected count less than 5. The use, the p-value (Asymp. Sig) in each case is minimum expected count is 2.40. reported as “.000”, we would report this as p<0.0005. (Note in this case the Pearson method has a note suggesting we use an alternative, we can though use the next one down. ) A way to show this graphically… A bar chart would be useful to give an idea of the number of respondents from each school; we can go a step further and illustrate the male/female ratio at the same time. In the example here the height of the bar gives the number of respondent and the bar is stacked to show the male to female ratio for each bar. Questionnaire design and analysing the data using SPSS page 11 To get this graph I used the old fashioned graph method, now tucked away under “Graphs, Legacy dialogs, Bar”, notice that in the initial dialog box for this method we have the option to go for a stacked bar chart, if you don’t want a stacked bar chart then leave it set at “simple” , the resulting dialog will not be as complex since you wouldn’t have to say which variable to use for the stacking. This method could easily be applied to other questions where the answers were categorical, for example the question about travel. A brief recap about analysing “tick one only” type questions. The data are coded into a single variable; this can take on one of five values in this example, depending upon the respondents’ choice. The numbers 1-5 used to code the data are given labels as previously described. This time a “Simple” bar chart can be requested from the legacy graph menu. The result isn’t too spectacular in this case, because the travel modes are similar in this small sample, a larger sample would have given more chance of people using the less popular methods. The next two ways of addressing the transport question give richer data but at a severe price in data handling complexity. The third type (ranking) can be simplified to “skim off” data similar to this example if it all gets too confusing. Questionnaire design and analysing the data using SPSS page 12 Analysing “tick all that apply” type questions. The above question could be coded and stored in SPSS by allocating one variable to each option (Walk, Car etc.) The file “Travel 2.sav” has some fictitious data in for you to play with. The responses are coded as 1=yes and 0 = no, the gender variable is included to illustrate that this is just part of a larger set of responses that might all have been stored in the same file. Analysing this structure is not as simple as when the respondent can only give one response. The Frequencies method (Analyse, Descriptive stats, frequencies) can be used to calculate the total number of votes for each type of transport by putting the five variables into the variables box and then clicking the “Statistics” button on the frequencies dialog box and asking for the “Sum” of each variable. To get a graph you can use the Interactive legacy bar chart. The trick is to select all the necessary variables at once, do this by clicking on the first one then holding the shift key while clicking the last one. When they are selected drag them all to the horizontal axis (see the diagram). The “Specify labels” dialog should then appear, just OK this and finally, back in the “Create bar chart” dialog, select “Sums” instead of “Means” in the “Bars represent value” box at the bottom of the dialog box. You can now hit “OK”. The bars are in alphabetical order, this I expect can be altered, but frankly I’d rather not try! You might have a go at dragging the gender variable to the “Panel variables” box. Do though “Reset” this dialog before trying more tricks, it doesn’t like being used in this way. Questionnaire design and analysing the data using SPSS page 13 Analysing “Ranking” type questions. The data for this question, again fictional, are stored in the file called “Travel 3.sav”. A similar graph can be constructed as above, in the “tick all that apply” example but you might consider using the Median rather than the sum. Another issue is that although the respondent is probably happier grading their most popular travel mode as a "one", rather like a league table, the reader of the resultant graph would typically expect to see the taller bars representing the more popular choices. This isn’t the case unless you recode the data. Recoding data is a little involved, the command lives under the transform menu. The safe way to play with it is to use the “Save as” command to save a copy with a new name and play on that copy. The second graph here was done on recoded data and shows more clearly the popularity of each method. ---------------------------------------------------------In summary; Questionnaire data analysis. What type of data do you have? Remember that different statistical procedures are appropriate for types of data and of course what you want to show! The choices are limited by the level of measurement of the variable(s) to be analysed. Questionnaire derived data are likely to be nonparametric. The exception would be if you had people fill in their height or weight. Questionnaire design and analysing the data using SPSS page 14 The categorical or nominal variables resulting from this method of data gathering provide a list of choices with no meaningful order to the list, e.g. our first travel question, or hair colour. The mean of a categorical variable is meaningless. Use the mode, frequency tables and crosstabulations with categorical variables. To illustrate this type of data, use bar charts (or pie charts if you wish to show proportion). Ordinal variables have an implied order to the response choices. (e.g. 1= strongly agree, 2= agree, etc.) Typically use the median and mode for these variables, frequency tables (possibly even cumulative frequencies – but don’t get carried away) and crosstabulations. Bar charts can display results usefully. If your questionnaire yields some continuous variables (e.g. age in years where we know each year is the same distance apart from the next) we can apply many more statistics and if we really want we can condense them down into ordinal groups, (e.g. if we know the actual age we could reclassify the data into age groups.) -----------------------------------------------------------------SPSS Inc. (2004). SPSS Survey Tips [online], SPSS Inc. Last accessed on 3/11/2008 at: http://www.spss.com/PDFs/STIPlr.pdf University Computing Services, The University of Leeds (1996). Guide to the Design of Questionnaires. The University of Leeds Last accessed on (latest version) 3/11/2008 at: http://iss.leeds.ac.uk/info/312/surveys/217/guide_to_the_design_of_questionnaires/5 BUCKINGHAM, Alan and SAUNDERS, Peter (2004). The Survey Methods Workbook. Polity ------------------------------------------------The data and latest copy of the exercises will be available at; http://teaching.shu.ac.uk/hwb/ag/resources/resourceindex.html