PRENTICE HALL Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458

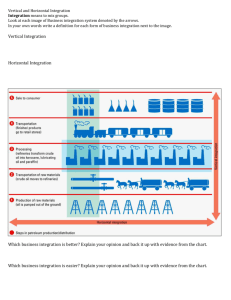

advertisement

PRENTICE HALL

Upper SaddleRiver, New Jersey07458

,...

areas after selling off the milling operations, the old core of the company. ...[In

these

cases],however, new management was brought in and acquisition and divestment used to

make the transition. So, even though vestiges of the old name remain, these are substantially different companies. ...

The vast majority of our researchhas examined one kind of strategic change-diversification. The far more difficult one, the change in center of gravity, has received far less

[attention]. For the most part, the concept is difficult to measureand not publicly reported

like the number of industries in which a companyoperates.Casestudies will have to be used.

But there is a need for more systematic knowledge around this kind of strategic change.

by Henry

Mintzberg

The "one best way" approach has dominated our thinking about organizational structure

since the turn of the century. There is a right way and a wrong way to design an organization. A variety of failures, however, ha.~made it clear that organizations differ, that, for

example, long-range planning systemsor organizational development programs are good for

some but not others. And so recent managementtheory has moved away from the "one best

way" approach, to"'ard an "it all depends" approach, fonnally known as "contingency theory." Structure should reflect the organization's situation-for example, its age,size,type of

production system,the extent to which its environment is complex and dynamic.

This reading arguesthat the "it all depends" approachdoes not go far enough, that structures are rightfully designed on the basisof a third approach, which might be called the "getting it all together" or "configuration" approach. Spansof control, types of fonnalization and

decentralization, planning systems,and matrix structures should not be picked and chosen

independently, the way a shopper picks vegetablesat the market. Rather, these and other elemcnts of organizational design should logically configure into internally consistent groupings.

When the enonnous amount of researchthat has been done on organizational structure is looked at in the light of this conclusion, much of its confusion falls away,and a convergence is evident around several configurations, which are distinct in their structural

designs, in the situations in which they are found, and even in the periods of history in

which they first de\'eloped.

To understand these configurations, we must first understand each of the elements that

make them up. Accordingly, the first four sections of this reading discussthe basic pans of

organizations, the mechanisms by which organizations coordinate their activities, the parameters they use to design their structures,and their contingency, or situational, factors. The

final section introduces the structural configurations, each of which will be discussed at

length in Section III of this text.

,

Six Basic Parts of the Organization

At the base of any organization can be found its operators, those people who perform the

basic work of producing the products and rendering the services.They form the operating

core. All bur the simplest o~nizations also require at leasr one full-rime manager who

.Excerpted originally from The StructUring0{ Organizacions(Prentice Hall. 1979). with added secrions from

Power in and ATOundOrganizalions (Prentice Hall. 1983). This chapter was rewritten for this edition of the text.

basedon two other excerptS: "A Typology of Organizational Structure." published as Chapter 3 in Danny Miller

and Peter Friesen. Organizalions: A Quanntm View. (Prentice Hall. 1984) and "Deriving Configurations,"

Otapter 6 in MinlZbeTgon Management: InsideOUT SLTange

World of Organizalions (Free Press,1989).

CHAPTER6 33 I

Dealingwith Structure and Systems T

occupies what we shall call the strategicapex,where the whole system is overseen. And as

the organization grows, more managersare needed-not only managersof operators but also

managers of managers. A middleline is created, a hierarchy of authority between the Operating core and the strategic apex.

As the organization becomesstill more complex, it generally requires another group of

people, whom we shall call the analysts.They, too, perform administrative duties-to plan

and control formally the work of others-but of a different nature, often labeled "staff."

These analysts form what we shall call the technosm4CtUTe,

outside the hierarchy of line

authority. Most organizationsalso add staff units of a different kind, to provide various internal services, from a cafeteria or mailroom to a legal counselor public relations office. We

shall call these units and the part of the organization they form the support staff.

'Finally, evety active organization has a sixth part, which we call its ideology(by which

is meant a strong "culrure"). Ideology encompassesthe traditions and beliefs of an organization that distinguish it from other organizationsand infuse a cenain life into the skeleton

of .its strucrure.

This gives us six basic pans of an organization. As shown in Figure 1, we have a small

strategic apex connected by a flaring middle line to a large, flat operating core at the base.

These three parts of the organization are drawn in one uninterrupted sequence to indicate

that they are typically connected through a single chain of formal authority. The technostructure and the support staff are shown off to either side to indicate that they are separate

from this main line of authority, influencing [he operating core only indirectly. The ideology is shown as a kind of halo that surrounds the entire system.

These people, all of whom work inside the organization to make its decisions and take

its actions-full-time employeesor, in some cases,committed volunteers-may be thought

of as inJluencerswho form a kind of internal coalition. By this term, we mean a systemwithin which people vie among themselvesto determine the distribution of power.

In addition, various outside people also try to exert influence on the organization, seeking to affect the decisions and actions taken inside. These external influencers, who create

a field of forces around the organization, can include owners, unions and other employee

FIGUREl

The Six Basic Parts of

the Organi:ation

Id~logy

(

332

CHAPTER6

..Dealin~

with Structure and Systems

~

,

associations.suppliers. clients, partners, competitors, and all kinds of publics, in the form of

governments, special interest groups,and so forth. Together they can all be thought to form

an external coalition.

Sometimes the external coalition is relatively passive(as in the typical behavior of the

shareholdersof a widely held corporation or the members of a large union). Other times it

is dominaredby one active influencer or some group of them acting in concert (such asan

outside owner of a businessfirm or a community intent on imposing a certain philosophy

on its school system). And in still other cases,the external coalition may be divided,as different groups seek to impose contradictory pressureson the organization (as in a prison buffeted between two community groups, one favoring custody,the other rehabilitation).

six BasicCoordinating Mechanisms

E\'ef)' organized human activity-from the making of pottery to the placing of a man on

the moon~ives rise to two fundamental and opposing requirements: the dit'ision of labor

into \'arious tasks to be performed and the coordinationof those tasks to accomplish the

acti\'iry. The structure of an organization can be defined simply as the total of the \\'ays in

which its labor is divided into distinct tasks and then its coordination achieved among

those tasks.

I.

2.

M/lc/uti adjuscmencachieves coordination of work by the simple process of inforntal

communication. The people who do the work interact with one another to coordinate,

much as tWo canoeists in the rapids adjust ro one another's actions. Figure 2a shows

mutual adjustment in terms of an arrow betWeentWo operators. Mutual adjustment is

obviously used in the simplest of organizations-it is the most obvious way to coordinate. But, paradoxically, it is also used in the most complex, because it is the only

means that can be relied upon under extremely difficult circumstances, such astrying

to figure out how to put a man on the moon for the first time.

Direct .~u/x.'T1li.~i/Jn

in which one person coordinates by giving orders to others, tends to

come into play after a certain number of people must work together. Thus, fifteen people in a war canoe cannot coordinate by mutual adjustment; they need a leader who,

by virtue of instructions, coordinates their work, much as a football team requires a

quarterback to call the plays. Figure 2b showsthe leader as a manager with the instructions as arrows to the operators.

Coordination can also be achieved by standardization-in effect, automatically, by

virtue of standards that predetermine what people do and so ensure that their work is coordinated. We can consider four forms-the standardizationof the work processesthemselves,

of the ourputs of the work, of the knowledge and skills that serve as inputs to the work, or

of the norms that more generally guide the wor}}.

3.

4.

Sttl11dardization

of work processes

means the specification-that is, the programmingof the content of the work directly, the proceduresto be followed, as in the caseof the

assemblyinstructions that come with many children's toys. As shown in Figure 2c, it is

typically the job of the analysts to so program the work of different people in order to

coordinate it tightly.

Standardizationof outputs means the specification not of what is to be done but of its

results. In that way, the interfaces between jobs is predetermined, as when a machinist

is told to drill holes in a certain place on a fender so that they will fit the bolts being

welded by someone else,or a division manageris told to achieve a sales growth of 10%

so that the corporation can meet some overall salestarget. Again, such standardsgenerally emanate from the analysts, as shown in Figure 2d,

CHAPTER 6 333

Dealingwith Structure and Systems T

-.

.'."..

FIGURE2

The Basic Mechanisms

of Coordination

-"

0"

,-Co

I

0

a) Mutual Adjustment

c) Standardizationof Work

5.

6.

-r0

b) Direct Supervision

d) Sundardization of Outputs

Standardizationof skil~. as well as knowledge, is anothet, though looser \vay to achieve

coordination. Here, it is the worker rather than the work or the outputs that is standardized. He or she is taught a body of knowledge and a set of skills \vhich are sub5equently applied to the work. Such standardization typically takes place outside the

organization-for example in a professional school of a university before the \vorker

takes his or her first job-indicated in Figure 2e. In effect, the standardsdo not come

from the analyst; they are i~ternalized by the operator as inputs to the job he or she

takes. OJOrdination is then achieved by vinue of various operators' having learned

what to expect of each other. When an anesthetist and a surgeon meet in the operating room to remove an appendix, they need hardly communicate (that is, use mutUa)

adjustment, let alone direct supervision); each knows exactly what the other \vill do

and can coordinate accordingly.

Standardizationof norms means that the workers share a common set of beliefs and can

achieve coordination based on it, as implied in Figure 2f. For example, if eve!)' member of a religious order sharesa belief in the imponance of attracting converts, then all

will work together to achieve this aim,

These coordinating mechanisms can be considered the most basic elements of strUcture, the glue that holds organizations together. They seem to fall into a rough order: As

334

'If'

CHAPTER6

Dealing with Structure and Systems

organizational work becomes more complicated, the favored means of coordination seems

to shift from mutual adjustment (the simplest mechanism) to direct supervision, then to

standardization, preferably of work processesor norms, otherwise of outputs or of skills,

finally reverting back to mutual adjustment. But no organization can rely on a single one of

those mechanisms; all will typically be found in every reasonablydeveloped organization.

Still, the important point for us here is that many organizations do favor one mechanism over the others, at least at certain stagesof their lives. In fact, organizations mat favor

none seem most prone to becoming politicized, simply becauseof the conflicts that naturally arise when people have to vie for influence in a relative vacuum of power.

~

Tile Essential Parameters of Design

The essenceof organizational design is the manipulation of a seriesof parametersthat determine the division of labor and the achievement of coordination. Some of these concern the

design of individual positiorlS, others the design of the superstructure (the overall network

of subunits, reflected in the organizational chan), some the designof lateral linkages to flesh

out that superstructure, and a final group concerns the design of the decision-making system of the organization. Listed as follows are the main parametersof structural design, with

links to the coordinating mechanisms.

...Job specialization refers to the number of tasks in a given job and the workers' control

over these tasks. A job is horizontallyspecializedto the extent that it encompassesa few

narrowly defined tasks, verticallyspecialized to the extent that the worker lacks control

of the tasks perfonned. Unskilled jobs are typically highly specialized in both dimensiorlS;skilled or professionaljobs are typically specializedhorizontally but not venically.

"Job enrichment" refers to the enlargement of jobs in both the vertical and horizontal

dimerlSion.

...Behavior

fonnalization refers to the standardization of work processesby the imposition of operating irlStructions, job descriptiorlS, rules, regulatiorlS, and the like.

Structures that rely on any fonn of standardization for coordination may be defined as

bureaucratic,those that do not as organic.

...Training

refers to the useof fonnal irlStructional programsto establish and standardize

in people the requisite skills and knowledge to do panicular jobs in organizatiorlS.

Training is a key design parameter in all work we call professional. Training and formalization are basically substitutes for achieving the standardization (in effect, the

bureaucratization) of behavior. In one, the standards are learned as skills, in the other

they are imposed on the job as rules.

...Indoctrination

refers to programsand techniques by which the nonns of the members

of an organization are standardized,so that th~y become resporlSiveto its ideological

needs and can thereby be trusted to make its decisiorlS and take its actiorlS.

Indoctrination too is a substitute for formalization, as well as for skill training, in this

case the standards being internalized as deeply rooted beliefs.

...Unit

grouping refers to the choice of the basesby which positiorlSare grouped together into units, and those units into higher-order units (typically shown on the organization chan). Grouping encourages coordination by putting different jobs under common supervision, by requiring them to share common resourcesand achieve common

measures of perfonnance, and by using proximity to facilitate mutual adjustment

among them. The various basesfor grouping-by work process,product, client, place,

and so on-can be reduced to tWo fundamental ones-me function perfonned and the

marketserved.The fonner (illustrated in Fig. 3) refers to means, that is to a single link

CHAPTER6 335

Dealing with Structure and Systems

"Y

8'

~

FIGURE

,

3

!

I

Grouping

A Cultural

by Function:

!

Center

Finance

Operations

Public

Relations

Box Office

Maintenance

and Garage

in the chain of processesby which products or services are produced; the latter (in Fig.

4) to ends, that is. the \vhole chain for specific end products. services,or markets. On

what criteria should the choice of a basis for grouping be made?First, there is the consideration of workflow linkages, or "interdependencies." Obvi()Usly, the more tightl).

linked are p<)sitionsor units in the workflow, the more desirable that they ~e grouped

together to facilitate their c0<1rdination.Second is the consideration of prlxess interdependencies-for example, acrosspeople doing the same kind of work hut in different workflows (such as maintenance men working on different machii1cs). It sometimes makes senseto group them together to facilitate their sharing of equipment or

ideas,to encouragethe improvement of their skills, and Sl)on. Tl1ird is the question of

scale interdependencie.~.For example, all maintenance people in a factory may ha\.e to

be grouped together becauseno single department has enough maintenancc work for

one person. Finally, there are the social interdependencics, the need to ~'TOUp

people

together for s<xial reaS<1ns,

as in coal mines where mutual supp<)rtunder dangerous

working conditions can be a factor in deciding how to group people. Clearly, grouping

by function is favored by prlxess and scale interdependencies. anJ to a lL'Sserextent by

social interdependencies (in the sensethat people who do the samc kind of joh often

tend to get along better). Grouping hy function als<)encourages spcciali:ation, for

example, hy allowing specialiststo come together under the supervision of one of their

own kind. The problem with functional grouping, however. is that it narrows perspectives, encouraging a focus on means instead of ends-thc way to do the job instead of

the reaSl)nfor doing the job in the first place. Thus grouping by m,trket is usedto favor

coordination in the workflo\v at the expense of processand scale speciali:ation. In general, market grouping reducesthe ability to do specialized or repetitivc tasks well and

is more wasteful, being less able to take advantage of economies of scale and often

requiring the duplication of resources.But it enables the organization to accomplish a

wider variety of tasksand to change its tasks more easily to serve the organi:ation's end

markets. And so if the workflow interdependencies are the important ones and if the

organization cannot easily handle them by standardization, then it \vill tend to favor

the market basesfor grouping in order to encourage mutual'adjustment and direct

supervision. But if the workflow is irregular (as in a "job shop"), if standardi:ation can

easily contain the important workflow interdependencies, or if the process or scale

interdependencies are the important ones, then the organization will be inclined to

seek the advantagesof specialization and group on the basis of function instead. Of

"t"t"

C-:HAPTER6

!'(jURE 4

(;rtluping by Market:

The Canadian Post Office*

Atlantic

Postal

Region

Western

Postal

Region

South

Toronto

Nova

Scotia

Postal

District

Metro Area

Western

Proc.Plant I

II

Postal

Ontario

Postal

!

District

District

Montreai

Metro Area

Proc.Plant

Postal

~,~~_!_~

i

.Hcadquarter

scaff ~roups deleted.

Mantioba

Postal

District

Saskatchewan

Postal

District

course in all but the smallest organizations,the question is not so much which basisof

grouping, but in what order. Much as fires are built by stacking logs first one way and

then the other, so too are organizations built by varying the different basesfor grouping to take care of various interdependencies.

""

Unit size refers to the number of positions (or units) contained in a single unit. The

equivalent term, span of control, is not used here, becausesometimes units are kept

small despite an absenceof close supervisorycontrol. For example, when expens coordinate extensively by mutual adjustment, as in an engineering team in a space agency,

they will form into small units, In this case,unit size is small and span of control is low

despite a relative absence of direct supervision. In contrast, when work is highly stanCHAPTER 6 337

Dealingwith Structure and Systems "f'

"'"

""

dardized (because of either fonnalization or training), unit size can be very large,

becausethere is little need for direct supervision. One foreman can supervisedozensof

assemblers,becausethey work according to very tight instructions.

Planning and control systems are used to standardize outputs. They may be divided

into tWo types: action planning systems, which specify the results of specific actions

before they are taken (for example, that holes should be drilled with diametersof 3 centimeters)j and performancecontTolsystems,which specify the desired results of whole

ranges of actions after the fact (for example, that salesof a division should grow by 10%

in a given year).

Liaison devices refer to a whole seriesof mechanismsused to encourage mutual adjustment within and betWeenunits. Four are of particular importance:

Liaison positionsare jobs created to coordinate the work of tWo units directly, without having to pass through managerial channels, for example, the purchasing engineer who sits between purchasing and engineering or the sales liaison person who

mediates between the salesforce and the factory. These positions carry no formal

authority per sej rather, those who serve in them must use their lX)wers of persuasion, negotiation, and so on to bring the two sides together.

Task forces and standing committeesare institutionalized fonns of meetings which

bring membersof a number of different units together on a more intensive basis,in

the first caseto deal with a temporary issue,in the second, in a more permanent and

regular way to discussissuesof common interest.

Integratingmanagers--essentially liais<)npersonnel with fonnal authority-provide

for stronger coordination. These "managers" are given authority not over the units

they link, but over something important to those units, for example, their budgets.

One example is the brand manager in a consumer goods finn \vho is responsible for

a certain product but who must negotiate its production and marketing with different functional departments.

MatTix s~ctUre carries liaison to its natural conclusion. No matter what the bases

of grouping at one level in an organization, some interdependencies always remain.

Figure 5 suggestsvarious waysto deal with these "residual interdependencies": a different type of grouping can be used at the next level in the hierarchy; staff units can

be fonned next to line units to advise on the problems; or one of the liais<}ndevices

already discussedcan be overlaid on the grouping. But in each case,one basis of

grouping is favored over the others. The concept of matrix structure is balance

betWeen tWo (or more) basesof grouping, for example functional with market (or

for that matter, one kind of market with another--say, regional with pr(1duct).This

is done by the creation of a dual authority structure-rwo (or more) managers,

units, or individuals are made jointly and equally responsible for the same decisions.

We can distinguish a permanentfoFmof matrix structure, where the units and the

people in them remain more or less in place, as shown in the example of a whimsical multinational finn in Figure 6, and a shifting form, suited to project work, where

the units and the people in them move around frequently. Shifting matrix structures

are common in high-technology industries, which group specialists in functional

departments for housekeepingpurposes(processinterdependencies. etc.) but deploy

them from various departments in project teams to do the work, as shown for

NASA in Figure 7.

Decentralization refers to the diffusion of decision-making power. When all the power

restsat a single point in an organization, we call its structure centralized; to the extent

that the power is dispersedamong many individuals, we call it relatively decentralized.

We can distinguish vertical decentralization-the delegation of formal power down the

8

338

T

CHAPTER 6

Dealingwith Structure and Systems

T

,

Il<;VRE 5

~Irll.:turcs to Deal with

H",iJuallnterdependencies

b) Line and Staff Structure

c) Liaison OverlayStructure (e.g., Task Force)

FIGURE 6

A Permanent Matrix

StrUcturein an

International

Flrnl

hierarchy ro line managers-from horizontaldecentralization-the extent to which formal or informal power is dispersedour of the line hierarchy ro nonmanagers (operarors,

analysts, and suppon staffers). We can also distinguish selectitledecentralization-the

dispersal of power over different decisionsto different places in the organization-from

parallel decentralization-where the power over various kinds of decisions is delegated

to the sameplace. Six fonns of decentralization may thus be described: (1) venical and

horizontal centralization, where all the power restsat the strategic apex; (2) limited

horizontal decentralization (selective), where the strategic apex shares some power

with the technostructure that standardizeseverybody else's work; (3) limited venical

CHAPTER6 339

Dealingwith StructUreand Systems T

~

,

FIGURE i

~hiftin~MatrixStructure

I~~~I

m the NASA Weather

I~~

Satellite Program

Source:Modified from

Delbecqand Filley (1974:16).

--

decentralization (parallel), where managersof market-based units are delegated the

power to control most of the decisionsconcerning their line units; (4) venical and horizontal decentralization, where most of the power rests in the operating core, at the

bottom of the structure; (5) selective venical and horizontal decentralization. where

the power over different decisions is dispersedto various places in the organization,

among managers.staff expertS,and operatorswho work in teams at various levels in the

hierarchy; and (6) pure decentralization, where power is shared more or less equally by

all members of the organization.

The Situational Factors

A number of "contingency" or "situational" factors influence the choice of these design

parameters. and vice versa.They include me age and size of the organization; its technical

systemof production; various characteristics of its environment. such as stability and complexity; and itS power system. for example. whether or not it is tightly controlled by outSi~e

influencers. Some of me effectSof these factors, as found in an extensive body of research

literature, are summarized below as hypotheses.

(8

340 CHAPTER

6

..Dealing

with StruCtUre and Systems

i

t

1

.

AGE AND SIZE

'"

'"

'"

'"

'"

The older an organization, the more formalized its behavior. What we ha,.e here is

the "we've-seen-it-all-betore" syndrome.As organizations age, they tend to repeat their

behaviors: as a result, these become more predictable and so more amenable to formalization.

The larger an organization, the more formalized its behavior. Just as the older organization formalizes what it has seen before, so the larger organization formali:es what

it seesoften. ("Listen mister, I've heard that story at least five times today. Just fill in

the form like it says.")

The larger an organization, the more elaborate its structure; that is, the more specialized its jobs and units and the more developed its administrative components. As

organizations grow in size, they are able to specialize their jobs more finely. (The big

barbershop can afford a specialist to cut children's hair; the small one cannot.) As a

result, they can also specialize--or "differentiate"-me work of their units more extensively. This requires more effort at coordination. And so the larger organization tends

also to enlarge its hierarchy to effect direct supervision and to make greater use of its

technostructure to achieve c()()rdination by standardization, or else to encourage more

coordination by mutual adjustment.

The larger the organization, the larger the size of its average unit. This finding relates

to the previous two, the size of units growing larger as organizations thernsel,'es grow

larh'erhecause (I) as heha,'ior becomesmore formalized. and (2) as the work of each

unit hecomesmore homl~eneous, managersare able to supervisemore emplo)'ees.

Structure reflects the age of the industry from its founding. This is a curious finding,

but one that we shall see holds up remarkably well. An orh'anization'sstructure seems

to reflect the age of the industry in which it operates, no matter what its own age.

Industries that predate the industrial revolution seem to favor one kind of structure.

thl)sc of the age of the early railroads another, and so on. We should obviously expect

different structures in different periods; the surprising thing is that these structures

seem to carry through to ne\\' peril~s, old industries remaining relatively true to earlier structures.

TECHNICAL SYSTEM

Technic-'ll system refers to the instruments used in the operating core to produce thc outputs. (This should be distinb'Uishedftom "technoll1!,.'Y,"which refers to the kru)wlcdgc hasc

of an organization.)

I

I

1

i

I

I

I

I

1

...The

more regulating the technical system-that is, the more it controls the work of

the operator the more formalized the operating work and the more bureaucratic

the ...tructure of the operating core. Technical systems that regulate the work of the

operators--for example, massproduction assemblylines-render that work highly routine and predictable, and S()encourage its specialization and formalization. \\'hich in

turn create the conditions for bureaucracyin the operating core.

...The

more complex the technical system, the more elaborate and professional the

support staff. Essentially, if an organization is to use complex machinery, it must hire

staff experts who can understand that machinery-who have the capability to design,

select, and modify it. And then it must give them considerable power to make decisions concerning that machinery, and encourage them to use the liaison devices to

ensure mutual adjustment among them,

...The

automation of the operating core forms a bureaucratic administrative structure

into an organic one. When unskilled work is coordinated by the standardization of

CHAPTER6 34 I

Dealingwith Structure and Systems T

work processes,we tend to get bureaucratic structure throughout the organization,

becausea control mentality pervadesthe whole system. But when the work of the operating core becomes automated, social relationships tend to change. No". ir is machines,

not people, that are regulated. So the obsession with control tends ro disaprearmachines do not need to be watched over-and with it go many of the managersand

analystswho were needed to control the operators. In their place come the support specialists to look after the machinery, coordinating their own work by mutual adjustment.

Thus, automation reducesline authority in fuvor of staff expertise and reducesthe tendency to rely on standardization for coordination.

ENVIRONMENT

Environment refers to various characteristics of the organization's outside context, related

to markets, political climate, economic conditions, and so on.

T

T

T

T

The more dynamic an organization's environment, the more organic its structure. It

stands to reason that in a stable environment-where nothing changes-an organi:acion can predict its future conditions and so, all other things being equal, can easily reI\'

on standardization for coordination. But when conditions become dynamic-when th~

need for product change is frequent, labor turnover is high, and p<)litical conditions are

unstable-the organization cannot standardize but must instead remain flexible

through the use of direct supervision or mutual adjustment for c()()rdination, and :;0 it

must usea more organic structure. Thus, for example, am1ies,which (end to be highly

bureaucratic institutions in peacetime, can become rather org,mic when engaged in

highly dynamic, guerilla-type warfare.

The more complex an organization's environment, the more decentralized its structure. The prime reasonto decentralize a structure is that all the inft)rmation needed to

make decisions cannot be comprehended in one head. Tl111S.when the operations of

an organization are based on a complex body of knowIL-dge,there is usuallya need to

decentralize decision-making power. Note that a simple cnvironment can be srable or

dynamic (the manufacturer of dressesfaces a simple environmcnt yer cannot predict

style from one seasonto another), as can a complex one (tl1e spcci,llist in perfected

open heart surgeryfacesa complex task, yet knows what to expect).

The more diversified an organization's markets, the greater the propensity to split it

into market-based units, or divisions, given favorable economies of scale. Wl1en an

organization can identify distinct markers-geographical regions, clicnts, hut especially products and services-it will be predisp<)5edto split itself into hi~h level units on

that basis,and to give each a good deal of control over its own openttions (that is, to

use what we called "limited vertical decentralization"). In simple tenns, diversification

breeds divisionalization. Each unit-can be given all the functions ass()Ciatedwith itS

own markets. But this assumesfavorable economies of scale: If the operating core cannot be divided, as in the case of an aluminum smelter, also if some critical function

must be centrally coordinated. as in purchasing in a retail chain, then full divisionalization may not be possible.

Extreme hostility in its environment drives any organization to centralize it.~struCture temporarily. When threatened by extreme hostility in its envirl.)nment. the tendency for an organization is to centralize power, in other words, to fall back on itStightest coordinating mechanism, direct supervision. Here a single leader can ensure fast

and tightly coordinated responseto the threat (at least temporarily).

342

""

CHAPTER6

Dealingwith Structure and Systems

T

POWER

...The

greater the external control of an organization, the more centralized and formalized its structure. This imponant hypothesis claims that to the extent that an

organization is controlled externally, for example by a parent finn or a government that

dominates its external coalition-it tends to centralize power at the strategic apex and

to fonnalize its behavior. The reasonis that the two most effective ways to control an

organization from the outside are to hold its chief executive officer responsible for its

actions and to impose clearly defined standards on it. Moreover, external control forces

the organization to be especiallycareful about its actions.

...A

divided external coalition will tend to give rise to a politicized internal coalition,

and vice versa. In effect, conflict in one of the coalitions tends to spillover to the

other, as one set of influencers seeksto enlist the support of the others.

...Fashion favors the structure of the day (and of the culture), sometimes even when

inappropriate. Ideally, the design parameters are chosen according to the dictates of

age, size, technical system,and environment. In fact, however, fashion seemsto playa

role too, encouraging many organizations to adopt currently popular design parameters

that are inappropriate for themselves. Paris has its salons of haute couture; likewise

New York has its offices of "haute structure," the consulting firms that sometimes tend

to oversell the latest in structural fashion.

The Configurations

W~ have now intr(~uced various attributes of organizations--:parts, coordinating mechanisms, design parameters. situational factors. How do they all combine?

We proceed here on the assumption that a limited number of configurations can help

explain much of what is obsen'ed in organizations. We have introduced in our di~ussion

six ha.'iicparts of the organiz.1tion,six basic mechanisms of cl)()rdination. aswell as six basic

typcs of dccentrdlization. In fact. there seemsto be a fundamental corrcspondence between

all of thesc sixes, which can be explained by a set of pulls exerted on the organization by

each of its six parts, as shown in Figure 8. When conditions favor one of these pulls. the

as.'iociatcdpart of the organiZ:ltion becomeskey. the c()()rdinating mechanism appropriate

to itsclf hecomcs prime, and the form of decentralization that passespower to itsclf emerges.

1l1C organizatil)n is thus dra\\'n to design itself as a particular configuration. We list here

(scc Tahle I) and then intr(xiuce hriefly the six resulting configuration.-;, t()gether with a

seventh that tends to appear when no one pull or part dominates.

TABLE 1

CONFIGURATION

PRIME

~

COORDINAnNG

MECHANISM

Direct Supervision

Professional organizatitffi

Scandardizacion of

work processes

Srandardizacion of

Diversified organization

Scandardization of

Innovative organization

Mutual adjustment

Scandardization of

skills

outputs

Missionary organization

Political organization

norms

None

TYPE OF

KEY PART OF

ORGANIZATION

DECENTRALIZATION

Vertical and horizontal

centralization

Limited hori:ontal

Technustructure

decentralization

Operating core

Hotizontal

deccntrali:ation

Limited vertical

Middle line

decentralization

Support staff Selected decentralization

Decentralization

Ideology

None

Varies

CHAPTER 6 343

Dealingwith Structure andSystems ""

~

T

!

FIGURE 8

Basic Pulls on the

O"""anization

Politics: Pullin~ Apart

THE ENTREPRENEURIALORGANIZATION

i

344 CHAPTER 6

-no.,I;""

..,i..h ~"rll("fllrp ~nd Systems

..".

since size too drives the structure toward bureaucracy.Not infrequently the chief executive

purposely keeps the organization small in order to retain his or her personal control.

The classic caseis of course the small entrepreneurial firm, controlled rightly and personally by its owner. Sometimes, however, under the control of a strong leader the organizarion can grow ro large. Likewise, entrepreneurial organizations can be found in other sectors too, like government, where strong leaderspersonally control panicular agencies,often

ones they have founded. Sometimes under crisis conditions, large organizations also revert

temporarily to the entrepreneurial form to allow forceful leaders to try to save them.

THE MACHINE ORGANIZATION

The machine organization is the offspring of the Industrial Revolution, when jobs became

highly specializedand work became highly standardized. As can be seen in the figure above,

in contrast to entrepreneurial organizations, the machine one elaborates its administration.

First, it requires a large technostructure to design and maintain its systemsof standardization, notably those that formalize its behaviors and plan its actions. And by virtue of the

organization's dependence on these systems,the technostructUre gains a good deal of informal power, resulting in a limited amount of horizontal decentralization reflecting the pull

to rationalize. A large hierarchy of middle-line managersemergesto control the highly specialized work of the operating core. But the middle line hierarchy is usually structured on a

functional basis all the way up to the top, where the real power of coordination lies. So the

structure tends to be rather centralized in the vertical sense.

To enable the top managersto maintain centralized control, both the environment and

the production system of the machine organization must be fairly simple, the latter regulating the work of the operators but not itself automated. In fact, machine organizations fit

most naturally with massproduction. Indeed it is interesting that this strUcture is most

prevalent in industries that date back to t~ period from the Industrial Revolution to the

early part of this century.

THE PROFESSIONALORGANIZATION

CHAPTER 6 345

Dealing with Structure and Systems T

. '"

There is another bureaucratic configuration, bur becausethis one relies on the standardiza.

tion of skills rather than of work processesor outputs for its coordination, it emergesas dramatically different £Yomthe machine one. Here the pull to professionalizedominates. In having to rely on trained professionals-people highly specialized,but with considerable Control

over their work, as in hospitals or universiries-to do its operating tasks,the organization surrenders a good deal of its power not only ro the professionalsthemselves but also to the ass0ciations and institutions that selectand train them in the first place. So the Structure emerges

as highly decentralized horizontally; power over many decisions. both operating and strategic, flows all the way down the hierarchy, to the professionalsof the operating core.

Above the operating core we find a rather unique structure. There is little need for a

technostructure, since the main standardization occurs as a result of training that takes

place outside the organization. Becausethe professionalswork so independently, the sizeof

operating units can be very large,and few first line managersare needed. The sUpport staff

is typically very large too, in order to back up the high-priced professionals.

The professional organization is called for whenever an organization finds itself in an

environment that is stable yet complex. Complexity requires decentralization to highly

trained individuals. and stability enables them to apply standardized skills and so to work

with a good deal of autonomy. To ensure that autonomy, the production system must be neither highly regulating, complex. nor automated.

THE DIVERSIFIEDORGANIZATION

Like the professionalorganizarion, the diversified one is not so much .m inregrared organization as a ser of rather independent entiries coupled t(~erher by a hx)Seadminisrrative

srructure. Bur whercas those enrities of rhe professional organization arc individuals, in the

diversified one they are units in the middle line, generally called "divisions," exerring a

dominanr pull to Balkanize. This configurarion differs from the others in onc major respecr:

ir is not a complete structure, bur a parcial (lne superimposed on the others. Each division

has its own strucrure.

An organization divisionalizes for one reaS<)n

above all, becauseits pr(~ucr lines are

diversified. And that tends to happen most often in the largest and most mature organizations, the ones that have run out of opportunitieS-{)r have become bored-in their traditional markets. Such diversification encouragesrhe organization to replace functional by

market~basedunits, one for each distinct product line (as shown in the diversified organization figure), and ro gram considerable auronomy to each to run its own business.The

result is a limited form of decentralization down the chain of command.

How doesthe central head4uartersmaintain a semblance of control over the divisions!

Some direction supervision is used. But too much of that interferes with the necessarydivisional autonomy. So the headquarrers relies on performance control systems, in other

words, the standardization of outputs. To design these control systems,headquarterscreates

346 CHAPTER 6

...Dealin£

with Structure and Systems

T

T

,

a small technostructure. This is shown in the figure, acrossfrom the small central support

staff that headquarterssets up to provide certain services common to the divisions such as

legal counsel and public relations. And becauseheadquarters' control constitutes external

control. as discussedin the first hypothesis on power, the structure of the divisions tend to

be drawn toward the machine form.

THE INNOVATIVE

ORGANIZATION

,

I

I

,

None of the structuresso far discussedsuitsthe industries of our age,industries such asaerospace,petrochemicals, think-tank consulting, and film making. lllese organizations need

aN)Veall t(1innovate in very complex ways. The bureaucratic structures are too inflexible.

and the entrepreneurial one to() centralized. These industries require "project structures...

ones that can fuse experts drawn from different specialties into sm()()thly functioning creative teams. That is the role of our fifth configuration, the innovative organization, which

we shall aIM)call "adhocracy," dominated by the experts' pull to collaborate.

Adh(xracy is an organic structure that relies for coordination on mutual adjustment

am(mg its highly trdined and highly specialized experts, which it encouragesby the extensivc use of the liaiM)n devices--integrating managers,standing committees, and alJt)ve all

tao;kforces and matrix structure. Typically the experts are grouped in functional units for

housekL-epingpuTpt)5eS

but deployed in small market basedproject teams to do their work.

To these teams, 1()Catedall ove,' the structute in accordance \vith the decisions to be made.

is deleg;1tedlX)wer over different kinds of decisions. 5<)the structure hecomesdecentralized

sclL'Ctivelyin the vertical and horizontal dimensions, that is, pt)\ver is distributed unevenly,

all,)ver the structure, according to expertise and need.

All the distinctions of conventional structure disappearin the innovative or~anization.

;15can be seen in the figure above. With power basedon expertise, the line-staff distinction

evaporates. With power distributed throughout the structure. the distinction between the

strategic apex and the rest of the structure blurs.

These organizations are found in environments that are N)th complex and dynamic.

hecausethose are the ones that require sophisticated innovation. the type that calls for the

ct)()perative efforts of many different kinds of experts. One type of adhocracy is often associated with a production systemthat is very complex, sometimes automated, and so requires

a highly skilled and influential support staff to design and maintain the technical system of

the operating core. (The dashed lines of the figure designate the separation of the operating core from the adhocratic administrative structure.) Here the projects take place in the

administration to bring new operating facilities on line (as when a new complex is designed

in a petrochemicals firm). Another type of adhocracy produces its projects direcrly for its

clients (as in a think tank consulting firm or manufacturer of engineering prototypes). Here.

as a result, the operators also take part in the projects, bringing their expertise to bear on

CHAPTER 6 347

Dealingwith Structure and Systems T

,

them; hence the operating core blends into the administrative structure (as indicated in the

figure above the dashed line). This second type of adhocracy tends to be young on average,

becausewith no standard products or services,many tend to fail \vhile others escape their

vulnerability by standardizing some products or services and so converting themselves to a

form of bureaucracy.I

THE MISSIONARY ORGANIZATION

!

f

t

\

Our sixth configuration forms another rather distinct combination of the elements we have

been discussing. When an organization is dominated by its ideology, its members are

encouraged [0 pull together, and so [here [ends to be a loose division of labor, little job specialization, as well as a reduction of [he various forms of differentiation found in [he other

configurations--of the strategic apex from [he rest, of staff from line or administration from

operations, between operators, between divisions, and so on.

What holds [he missionary tc6e[her-that is, provides for its coordination-is the

standardization of norms, the sharing of values and beliefs among all its members. And the

key to ensuring this is their socialization, effected through the design parameter of indoctrination. Once the new member has been indoctrinated into the organization--once he or

she identifies strongly with the common beliefs-then he or she can be given considerable

freedom to make decisions. Thus the result of effective indoctrination is the most complete

form of decentralization. And becauseother forms of coordination need not be relied upon,

the missionary organization formalizes little of its behavior as such and makes minimal use

of planning and control systems.As a result, it has little techn()S[ruc[ure. Likewise, external professionaltraining is not relied upon, becausethat would force [he organization to surrender a certain control to external agencies.

Hence, the missionary organization ends up as an amorphous mass of members, with

little specialization as to job, differentiatipn asto part, division as to status.

Missionaries tend not to be very young organizations-it takes time for a set of beliefs

to become institutionalized as an ideology. Many missionaries do not get a chance to grow

very old either (with notable exceptions, such as certain long standing religious orders).

Missionary organizations cannot grow very large per se-they rely on personal contactS

among their members-althoUgh some [end to spin off other enclaves in the form of relatively independent units sharing the sameideology. Neither the environment nor the technical systemof the missionary organization can be very complex, becausethat would require

the use of highly skilled specialists,who would hold a certain power and status over others

and thereby serve to differentiate the structure. Thus we would expect to find the simplest

I We shall clarify in a later reading these tWObasic types of adhocracies. Toffler employed the term adhocracy in

his popular book Future Shock,but it can be found in print at least as far back as 1964.

348

'If'

CHAPTER 6

Dealingwith Structure and Systems

technical systems in these organizations, usually hardly any at all. as in religious orders or

in the primitive farm cooperatives.

THE POLITICAL ORGANIZATION

Finally, we come to a form of organization characterized, structurally at least, by what it

lacks. When an organization has no dominate part, no dominant mechanism of c()Qrdination, and no stable form of centralization or decentralization. it may have difficult), tempering the conflicts within its midst. and a form of organization called the political may

result. What characterizes its behavior is the pulling apart of its different parts, as shown in

the figure above.

Political organizations can take on different u)rms. Some are temporary,reflecting difficult transitions in strategy or structure that evoke conflict. Others are more permanent,

perhaps becausethe organization must face competing internal forces (say,between necessarily s[r()ng marketing and production deparTments),perhaps becausea kind ofpt)litical rot

has set in but the organization is sufficiently entrenched to SUppOrT

it (being, for example.

a m(lnopt)ly or a protected government unit).

Together, all these configurations seemto encomp,lSSand integrate a g()()ddeal of what

we kru)w abt)ut organizations. It should be emphasized however. that as presented, each

configur.ltion is idealized-a simplification, really a caricature of reality. No real organi:ation is ever exactly like anyone of them. although S()medo come remarkably close, while

othcrs seemto reflect combinations of them, sometimes in transition from one to another.

T!1e first five represent what seemto be the most common forms of organi:ations; thus

thesc \vill form the basis for the "context" section of this htx)k-I.,beled entrepreneurial,

mature, diversified, innovation. and professional.There. a reading in each chapter willl'e

devoted to each of these configurations, describing its structure, functioning, conditions.

strateh'Y-making process,and the issuesthat surround it. Other readings in these chapters

will look at specific strategies in each of these contexts, industry conditions, strategy technique.o;,and so on.

The other tWOconfigurations-the missionaryand the political-seem to be lesscommon. represented more by the forces of culture and conflict that exist in all organizations

than by distinct forms as such. Hence they will be discussed in the chapter that immediately follows this one, on "Dealing with Culture and Power." But becauseall these configurations themselves must not be taken ashard and fast, indeed becauseideology and politics work within different configurations in all kinds of interesting \vays,a final chapter in

the context section, on managing change. will include a reading called "Beyond

Configuration: Forces and Fonns in Effective Organizations," that seeksto broaden this

view of organizations.

CHAPTER 6 349

Dealingwith Structureand Systems T

MANAGING

Ford's customerservice division is successfullytrying out teams to better serve dealers and their

I

N THE MANIC RUSH to devise principles by which to manage and motivate companies, it is increasingly difficult to tell the big idea from the

fashionable quick fix. An idca, reengineering, say,is hailed as the newcure-all. A herd

of companiestears around chanting the new

mantra, often without clear strategic objectives. Then the rush to judgment begins:

"The best thing we ever did!" "No, an utter

flop!" And so it goes.

Take heart: That rare thing, a consensus,

RI,PORTI,R ASSOllA T[ Raji" M. I~(/o

'II)

FORTUNE

I\PRIL3.!'I'I:;

is beginning to evolve around a model corporation for perhaps the next 50 years-the

horizontal corporation. After more than

half a century during which the functional

hierarchy was the dominant-really the only

-model for organizational design, we are

on the cusp of a fundamental transition.

suggestsDavid Robinson, president of CSC

Index: "Changes in operating models arp '~

the tectonic shifts of the business worl

.

They don't happen often, but when they do.

they flatten the unprepared." In Robinson's

opinion, just such a change is under wa~':

'

"ployees, like this happy bunch at a Ford dealership in Virginia.

"It's a shift from [competing on] what we

make to how we make it." American Express Financial Advisors, which is moving

toward a more horizontal organization, sells

financial products-insurance and mutual

funds, for example. But its organizational

redesign focuses on how its financial plan~

(

sell

these

products,

"' 1!"' t-lationships

with

emphasizing

build-

customers.

..e horizontal corporation includes

these potent elements: Teams will provide

the foundation of organizational design.

They will not be set up inside departments,

like marketing, but around core processes,

such as new-product development. Process

owners, not department heads, will be the

top managers,and they may sport wonderfully weird titles; GE Medical Systemshasa

"vice president of global sourcing and order

to remittance."

Rather than focusing single-mindedly on

financial objectives or functional goals,the

horizontal organization emphasizescustomer satisfaction. Work is simplified and hierarchy flattened by combining related tasks

-for example, an account-management

process that subsumesthe sales,billing, and

service functions-and

eliminating work

that does not add value. Information zips

along an internal superhighway: The knowledge worker analyzes it, and technology

moves it quickly across the corporation instead of up and down, speeding up and improving decision-making.

Okay, so some of this is derivative; the obsessionwith process,for example,dates back

to Total Quality Management. Part of the

beauty of the horizontal corporation is that it

distills much of what we know about what

\()PII

~ 1000; ~nPT'IN~

01

MANAGING

works in managing today. Its advocatescall it

an "actionable model"-jargon for a plan

you canwork with-that allows companiesto

use ideas like teams,supplier-customer integration, and empowerment in ways that reinforce each other. A key virtue, saysPat Hoye,

dealer-service support manager at Ford Motor, is that the horizontal corporation is the

kind of company a customer would design.

The,customer, after all, doesn't care about

the servicedepartment's goals or the dealer's

,;;

--

sales targets; he just wants his car fIXed right

and on time-so the organization makes

those objectives paramount. In most cases,a

horizontal organization requires some employees to be organized functionally where

their expertise is considered critical, as in human resources or finance. But those departments are often pared down and judiciously

melded into a designwhere the real authority

runs along process lines. Done right, says

Frank Ostroff, a McKinsey consultant who

with former colleague Douglas Smith devised a clear, coherent architecture for the

new model in 1992,"the horizontal corporation can take you from 100 horsepower to

500 horsepower."

As never before, managemenJwill make

all the difference. Getting from here (the

vertical, functional organization) to there

(the horizontal, process-basedone) is quite

possibly the greatest managementchallenge

of our time. Unraveling lines of authority

92 FOR TUN E

APRIL 3. 1995

and laying out newones can entangle a com- Americans an array of AEFA financial

pany as quickly as a kitten will get tied up products like mutual funds, insurance, and ~

viti!

with a ball of wool. It is critical, experts say, investment certificates for a commission.

that processes be defined with adequate Only 30% of the planners stayed for four

breadth, which ensures that they span the years. Another problem: Selling on commiscompany and include customersand suppli- sion may be the norm in the industry, but

ers. The challenge, almost by definition, is people al AEFA believe illeaves them vulan epic one; you can't timidly test it in one nerable to tomorrow's competitors.

Like whom, precisely? Like Bill Gates, recorner of the organization. Says Mercer

plies Douglas Lennick, an executive vice

Management Consulting's David Miron:

"That's like building a house one room at a president, referring to Microsoft's yet-to-beapproved acquisition of Intuit, maker of

Quicken software, which allows usersto pay

bills, manage finances, and track inveslments online from their PCs. SaysLennick:

"The marketplace does not want cold calling

and adversarial tactics. Unless the industry

responds better to clients, they'll turn to the

equivalent of the automatic teller machine.

Quicken is an emerging torpedo boat." By

year-end AEFA intends to put an end to

cold calling and to award planners-and

managers-bonuses for scoring well on

client-satisfaction surveys.The goals of the

redesign are explicit: a 95% client-retention

rate, 80% planner retention after four years,

and annual revenue growth of 18%.

To reach these goals, AEFA knew it

.could not content itself with installing

teams at the front line and giving extra '.:Ij

.

tical responsibility, usually regional, and

"owns" a process that horizontally spans

the organization-a process like client satisfaction or account management. Below

the senior managers, 180 divisions have

been reconfigured into 45 clusters led by

group vice presidents, who own processes

like new planner integration.

Organizing by process calls for a difficult

and time-consuming hand-over of power,

something you don't hear much about amid

AMERICAN EXPRESS

all the hosannas when companies reorgaFINANCIAL ADVISORS

When a company is basking in the glow of nize. Says Lennick: "This creates a lot of

People are saying, 'How can you

21 % annual earnings growth over the past trauma.

take my district away from me?' " Simply defive years, it takes a special nerve to turn it

fining what job belongs in which process can

inside out. American Express Financial Advisors, based in Minneapolis, contributed a be confusing. "One of the beauties of the

hefty $428 million to its parent company's vertical, functional organization is that who

profit of $1.4 billion in 1994. But these rosy you report to and who's the bossis very, very ~

earnings disguised a thorny problem: heavy clear. The new systemcreates ambigui~ fo' ~

everybody," saysBarry Murphy, AEFA san-U

attrition of its 8,000 planners-independent

contractors who exclusively sell middle-class imated vice president of client service. For

time without a master plan. You never engage management in thinking about all the

customer accountabilities and all of the suppliers in the process flow." Yet ever larger

legions of companies are taking up tho-challenge. Four organizations that have started

down this road show how long and hazardous it canbe. They're well on their way-but

not there yet.

example, the executive team initially made

client acquisition part of the marketing process.Later the team decided it was more appropriately Murphy's job, since satisfying the

client begins at the very beginning.

Because AEFA is a successful company

with strong leadership,the strategic vision of

the redesign seems to be shared across the

company, which improves its chancesof success. Marilyn Pierson, a senior financial adviser in the Oeveland office, has taken to

morrow's. The focus on process,he says,is

not enough. A corporation must continually

be replenished by its core, functional disciplines-"the professionalexcellence that elevatesa company'sprocessesfrom bestpractices to competitive breakthroughs."

FORD MOTOR'S

CUSTOMERSERVICEDMSION

If proof were needed that the horizontal,

process-based corporation has widespread

ler's office, where specialized expertise was

deemed critical. The division has stopped

selling parts to independent repair shops directly, even though this was profitable, because it didn't contribute to customer

satisfaction and customer retention, the new

touchstones.

That's the right way to think about

something as fundamental as the transition

from a functional organization to a horizontal one, saysMcKinsey's Ostroff: "This

is not just about efficiency. It starts from

'Where do we want to be in ten years?

What business do we want to be in? What

are the processes that drive that?' " Ford

made building easy-to-repair cars one of

its core processes, and so rather than

pinching pennies, it has doubled staffing in

upstream engineering.

Dealer support is a second core process.

Dealers are independent businessmen, but

obviously Ford's effort to improve service

would be a nonstarter without their cooperation. To enlist it, Ford is simplifying the way

it works with dealersby reducing the battery

of functional experts-parts specialists,marketing incentive specialists,and many, many

more-dealers routinely dealt with.

Ford has abandoned its functional organ-

the Washington,D.C., area.

the new client-satisfaction surveys, which

she recently received back from her clients:

"It's very valuable. Ifwe want long-term clients, this is how we go about it."

Is going horizontal a euphemism for being

spreadtoo thin? Worries Brij Singh, a region

director based in Cleveland: "There is a lot

going on. My concern is that something

could fall through the cracks." AEFA's

single-minded focus on its horizontal design

may also have hobbled its ability to take

advantage of opportunities. While CEO

Harvey Golub is pushing American Express

to think more globally, AEFA has made few

moves to capitalize on the growth of a large

middle class in Asia and Latin America. This

is a characteristic weaknessof the horizontal

(e

corporation,

\1

Group's

argues

Philippe

Boston

Amouyal,

Consulting

who

attacked

the concept in a provocative article he co-authored. An organization obsessedwith satisfying today's customer is prone to miss to-

94

FORTUNE

APRIL3,1995

appeal, here it is: Even Detroit is among the

disciples. Ford's 6,200-e.mployeecustomer

service division is ripping up its organization

chart to focus on increasing customer satisfaction, a yardstick by which it trails not only

the Japanesebut even General Motors. Says

Ronald Goldsbeny, the mildly theatrical division general manager: "We looked to see

if anywhere in the division we had a quantifiable goal of 'fIX it right the first time.' We

couldn't find one. It shocked us."

After a 2 'h-year study, Ford announced

last fall that it was organizing around four

key processesthat create customer satisfaction on the service side of the business: Fixing it right the first time on time, supporting

dealers and handling customers, engineering carswith easeof service in mind, and developing service fixes quicker. Like most

companies going horizontal, Ford elected to

keep some employees organized in functions like employee relations or the control-

recognition of a customer problem. Now we

make decisions on the spot in out-of-warranty situations, and the customer service

rep backs us up." Despite widespread support from dealers, the pilots, which started

in the summerof 1993,will not be evaluated

till the summer of this year, when Ford will

decide whether they will be rolled out across

the country.

This raises a nagging question: Is Ford

moving fast enough? The company is just

beginning to experiment with systems that

complement the horiwntal organizational

design, like 360-degree performance reo

views. Budgets are still drawn up on departmental lines. SaysMarshall Roe, who head~

the division's businessstrategy and commu.

nications: "There are things we have to solvc:

before we pull the trigger. In the past if wc.

got close enough, we'd pull the trigger an(

pick up the pieces later."

continued

MANAGING

Still, managers who once competed for

resources now work in teams alongside finance folk and are actually putting money

they think they won't need back on the table. Dealers seem excited. The division has

its new structure in place. It has defined

comprehensive core processes.It has set the

bold stretch target of increasing customer

retention-the percentage of Ford owners

whose next car is also a Ford-from 60% to

80%. Each additional percentage point is

worth a staggering $100 millio~ in profits,

Ford estimates.

Trouble is, consumer perception is a

stubborn beast to ride. As it tools down the

horizontal highway, Ford will have its work

cut out for it staying abreast of competitors, who are also focusing on after-sales

service as never before. Says Ford's Donald Sparkman: "If you take too long, you

could miss the market." Which may explain why some industry veterans aren't

impressed. "They've set themselves a pretty big challenge. It's a noble goal," says

Jake Kelderman, executive director for industry affairs for the National Auto

Dealers Association, making a

game effort to stifle his skepticism:

"In this industry we hear a lot of talk about

doing things differently. The minute the

objectives are not achieved, people are off

to something else."

GE MEDICALSYSTEMS,

MILWAUKEE

Imagine a manufacturing operation

where the manager in charge confesses he

can't evaluate his three direct reports because he sees too little of them. Go down

two layers to a production associate, a union steward to boot, who sayshe won't talk

to his manager unlessthere is a problem becausehis manager has plenty

on his plate. (He does check

for E-mail messages daily,

though.) Chaotic, you wonder? Far from it. This is a

plant that has cut the time it I

takes for its order-to-remittance process-the

period

from when an order is received through shipment to

payment-by 40% over the

past three years.

GE Medical Systems is a

tale of delayering run riot.

I

In the Eighties, Frank Waltz took over th

"

Milwau~ee p~antthat r:nakesmagnetic re~~'

onance ImagIng machInes. The manageP

of the nearby X-ray and CT scanner facilities moved to other positions in the past

four years, so Waltz has assumed those

jobs as well. Over the past six years two

layers beneath him have been torn out altogether. In the X-ray facility, for instance, only a production manager stands

between him and 170 people on the factory floor. Says Waltz: "Every year the

organization changes. I would expect it

to change next year."

Bet on it: His boss, Serge

Huot. a direct French Canadian who is vice president of

global sourcing and order to

remittance, wonders in all seriousness if the organization

is delayering fast enough:

"In a big organization each

layer slows down the process.

By delayering you are giving

people the power to change.

Too many companies spend

too much time thinking

about this. By the time

;;;;...

McKinsey consultanJFrank Ostroff;39. is convincedthat thehorizontal organization is theblueprint for tomon-ow'scorporation. Weasked

him about how companiesare building this new organizationalform.

Is there a road mapto get from a functionalorganizationto a horizontal

that together,don't do this. It won't help,and youwould be better

off investingthe company'stime andenergygettingthe fundamentals right. You wantto usethe horizontalmodelwhereveryou can

perform better byhaving real-time,integrated,parallelwork-for

example,developingnew-productor account-management

teams.

one?

You must first do the analytical homework to understand what

it takes to achieve competitive advantage. Then you must determine what core processesdrive that and whether a cross-functional,

process-based organization will get you there. You don't just redesign work; you design an enabling organization that goes with it.

You. get that one-time improvement from redesigning work. And

you get coherent goals from strategically defining core processes.

Where is it appropriate?

This is not a magic bullet-{)bvious, but an important point. If

you don't have your businessfundamentals,the basic blocking and

tackling, do tha~first; Some of the fundamentalsforhigJ;l-peiformine;companie~ are a:demanding CEO

Most companiesseem to be movingtoward a hybrid of the functional

and the horiZontalcorporation.

Most will be a hybrid. The pure horizontal model is appropriate

for the whole business maybe 10% of the time. We've had the vertical org chart hard-wired on our brains. Executives couldn't visualize anything else. The model helps people see new possibilities.

Howdo you maintain functional expertise?

On a continuum, you can say,"Where do we need functional expertise above all else?" If it's more important than anything, keep

strict functions. "Where are we better served by working in a real~me,p~llel

way?"That's where you go horizontal. There are innical pools, ~ntechAl

so, comparnes

~Thp.

i;;~l:

96 FORTUNE

APRIL3,1995

(~

do it, the train's passed them."

, !i;; hen you're as flat as GE Medical is.in

Ilwaukee, a lot of what some companies

see as the niceties of the horizontal corporation are revealed to be necessities. Waltz

is perfectly matter-of-fact about why production associates routinely visit GE facilities in Europe: "They see things the managers don't see." Elsewhere, people use

360-degree appraisals to shift employee focus-for example, to get employees to pay

home, lies down, and listens to music for an

hour to recoup. Barb Barras,who started out

at the plant 23 years ago in an entry-level position in subassembly production, says her

colleagues' response to the delayering is

mixed; people like the greater responsibility,

but some dislike the accountability that goes

with it. In her current position she usesCAD

systemsto plot the production process flow,

a job reservedfor engineers until a couple of

years ago. Says Barras: "Twenty years ago

partment, BCG advised, look at illnessto recovery as a process with pit stops in admission, surgery, and a recovery ward.

What this means in practice is that patients now meet a surgeon and a doctor of

internal medicine together, for instance,

rather than separately, which results in better care and fewer hospital visits. Says Mikael Lovgren, a BCG consultant who

worked with Karolinska: "Hospitals don't

think along the patient dimension. They

think only in terms of specializations"-not

unlike many companies that manage only

their functions and thereby obscure their

line of vision to customers.

Karolinska's problems as it began to

transform itself into a horizontal organization were compounded by the fact that it

had recently been through a major decentralization, which had created 47 departments marching to their own drums. Tribalism is the human condition, it seems,within

hospitals as well as corporations. Lindsten

had brought the number down to 11,but coordination was still woefully haphazard. Patients had to scale the high walls between

functions, often making multiple all-day visits to the hospital for tests. A patient with an

enlarged prostate gland spent, on average,

an astounding 255 daysafter his first contact

with the hospital before it was treated; only

',-"

.;'"";::;~:.;::

attention

to

Waltz

has

comes

me,

minutes

pleasing

a more

basic

reason:

do

cility,

are

a team

and

needed

to

install

years

to

ago

in part

since

calibration

first

this,

ou

haven't

Bob

the

asked

Claudio,

in testing.

We're

ty, he confirms:

98 FORTU

and

quarter

N E

you

report

to

better

way

to do

this."

know

KAROLINSKA

of

me

assothe

time

case

at

about

tive,

did

associates

radiation

tests

The

that

cr

a delivery

1994.

Bob.

after

APRIL3,1995

felt

in its

20%.

lan

the

the

stress,"

group

leader

There's

plen-

work

a

it could

care.

When

fessional