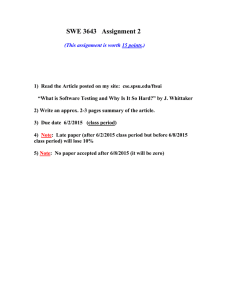

Free

advertisement