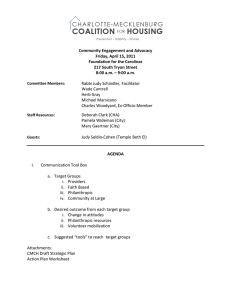

Housing and homelessness plan - Kenora District Services Board

advertisement