The Economic Theory of Regulation after a Decade of

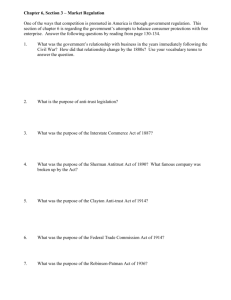

advertisement