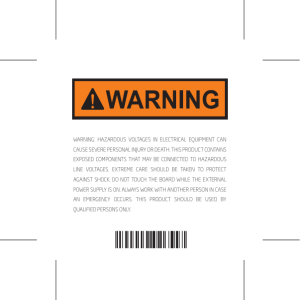

Understanding Hazardous Area Sensing

advertisement