SWSW Business Case for Public Sector Investment

advertisement

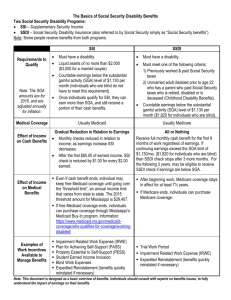

SWSW Business Case for Public Sector Investment October 2010 Background Minnesota was one of five states that participated in the Demonstration to Maintain Independence and Employment funded by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Under this research Demonstration, the Minnesota Department of Human Services (DHS) developed an intervention – Stay Well, Stay Working (SWSW) – that offered working persons with a serious mental illness (SMI) a comprehensive set of health, behavioral health, and employment support services. The goals of the research Demonstration were to: 1. Create a comprehensive and coordinated set of health care, behavioral health, and employment based supports for employed individuals with SMI; 2. Determine how access to and utilization of these services and supports influences the progression of potentially disabling conditions; and 3. Prevent or delay a person with SMI from becoming disabled and no longer able to work. Stay Well, Stay Working Outcomes The three-year SWSW evaluation used a randomized design and found the following participant outcomes: ■ Fewer applications to Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) ■ Improved functioning, reductions in limitations in ADLs/IADLs ■ Improved mental health status ■ Higher earnings and greater job stability ■ Greater connection to a regular medical provider or clinic for routine care and preventative services ■ Lower rates of medical debt ■ Less likely to delay or skip needed cared because of cost ■ Better quality of life Introduction Mental illnesses have a huge impact on disability and healthcare costs, as well as on employee productivity. According to the World Health Organization, mental and behavioral disorders affect more than 25 percent of people at some time during their lives. They are present in about 10 percent of the adult population at any point in time and are a growing cause of years lost to premature death or disability (Disability www.staywellstayworking.com Adjusted Life Years (DALYS)). Mental and neurological disorders accounted for 10 percent of years lost to premature death or disability1 from all conditions in 1990, 12 percent in 2000 and are projected to increase to 15 percent by 2020.2 Depression accounted for the most years living with a disability (11.9%), and ranks as the fourth leading cause of burden among all diseases, accounting for 4.4 percent of DALYS.3 1 SWSW Business Case for Public Sector Investment - October 2010 Burden on Employers Preventing Mental Health Disability In the United States, workers who have mental health problems are a significant and sometimes hidden cost for employers. A 2008 survey of a nationally representative sample of American workers found that one third experienced signs of clinical depression.4 A 2002 survey estimated that major depression decreased productivity by 8.4 hours per week, the most significant single reason for reduced productivity.5 The cost to employers is considerable; different studies have estimated the cost of lost productivity from clinical depression through absences and productivity decreases at $44 billion. Based on its 2003 short-term disability claims for psychiatric conditions, Metlife estimated the total cost to employers of lost productivity plus medical fees at $344 billion annually.6 Increasingly, health insurance covers mental health benefits and some employers offer Employee Assistance Services, which are often more acceptable to employees and their families than seeking assistance from psychiatric or mental health providers for emotional and behavioral problems. These efforts are effective in reducing the productivity and absentee problems often created by untreated mental health conditions. Multiple studies of company Employee Assistance Programs (EAP’s) find robust return on investment in lower absenteeism and higher productivity.13 People who get treatment for mental health problems use less general medical care than those who do not get mental health treatment.14 Two out of three employees who seek care for workplace issues or mental health problems were no longer work impaired after 21 weeks of treatment.15 Depression and anxiety also interact with other health conditions to increase productivity loss or disability absences even more.7 Sixty-four percent of individuals with physical concerns (musculoskeletal, cardiac, etc.), or with extended long term disability claims, have psychological concerns that delay improvement in their physical health.8 Anxiety or depression in combination with a physical illness is a better predictor of eventual functional impairment than the severity of the physical illness.9 The Rising Incidence of Mental Health Disability Mental illness is also a rising cause of disability and increased reliance on Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI). In 1999, a little more than a quarter (27%) of beneficiaries were diagnosed with a mental disorder,10 and this number increased to approximately one third in 2009.11 The federal government also provides the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program and Medicaid coverage for disabled individuals who do not have sufficient work history to qualify for SSDI, and for those SSDI recipients who fall below the program’s income standards. In December 2008, a full 60 percent of non-elderly SSI recipients were diagnosed with a mental disorder.12 2 However, there have been few efforts to prevent disability, and the current regulations of the SSI and SSDI programs create strong incentives to minimize employment in order to ensure continued eligibility. This means that once people become eligible for one of these programs, they must find lucrative and stable employment to consider leaving the program. Though the Social Security Administration is experimenting with reducing disincentives to work and developing programs that support employment, SWSW is one of the few programs for people with mental illness in the workforce that is designed to prevent disability. It is also notable as one of few formally evaluated Demonstrations of combining health care, navigation and employment supports to prevent disability. This Demonstration is highly relevant because the SWSW population is similar in many ways to currently uninsured people who will soon get coverage under the provisions of the Affordable Care Act. One third of SWSW participants had incomes under 133 percent of the federal poverty level, which is the future eligibility standard for Medicaid. The remainder would become eligible for other subsidized or employer provided health insurance options. As health care becomes available to this www.staywellstayworking.com SWSW Business Case for Public Sector Investment - October 2010 group, navigation and employment support, the other components of the SWSW program, will become an affordable alternative for preventing or postponing disability claims. income support programs, program participants and their employers derived from the program. It estimates the costs of implementing this program for a hypothetical cohort of 3,000, and shows that the potential savings in reduced dependence on public programs and increased taxes paid into the Social Security system repay the investment in the third year following program participation. About This Brief This brief describes the costs of the SWSW program, and the benefits that government Table 1: SWSW Costs Cost for Federal Grant Period (Sept 06 through Sept 09) Cost Category Provider Total Project Cost PMPM Cost of Full Operations (June 08 through Sept 09) Total Project Cost PMPM Program Management and Oversight Department of Disability Services $1,100,211.24 $43.80 $304,825.65 $15.06 Enrollment and Eligibility Determination Department of Disability Services $1,292,676.13 $51.46 $616,865.27 $30.47 SWSW Administration Medica $785,018.45 $31.25 $253,631.56 $12.53 Health and Behavioral Health Care Coverage Medica $20,678,621.67 $823.16 $17,074,420.28 $843.43 Reinsurance Stop Loss Secondary Insurer $221,726.96 $8.83 $172,570.16 $8.52 Navigation and Employment Counseling Minnesota Resource Center $1,835,228.52 $73.06 $1,122,468.20 $55.45 Employment Services Minnesota Resource Center $246,510.00 $9.81 $200,376.50 $9.90 Employee Assistance Optum $23,813.00 $0.95 $18,536.00 $0.92 WRAP Consumer Survivor Network $7,312.10 $0.29 $2,802.10 $0.14 $26,191,118.07 $1,042.60 $19,766,495.72 $976.41 $5,290,769.44 $210.61 $2,519,505.28 $124.46 Total Cost Total Cost of Navigation and Related Services (less health care and reinsurance) Source: Dept. of Disability Services Contract Expenditures Report and Special Reports, PMPMs from Medica data Costs of SWSW The SWSW program cost a total of $26.2 million over the federal grant period, September 2006 through September 2009 (evaluation costs are excluded from this total.)16 Table 1 shows how these costs were divided between the Minnesota Department of Human Services, Disability Services Division (DHS), Medica, the prime contractor, and other subcontractors, and the key functions each provided. A total of 25,121 member months of service were delivered at an average cost of $1,042.60 By www.staywellstayworking.com far the costliest element of the program was health care coverage, which amounted to $20.7 million, or approximately $823 per member per month (PMPM). The cost of all other navigation and employment related elements totaled $5.3 million or $210.61 PMPM. As a Demonstration program, SWSW experienced a slow initial enrollment period. Therefore, we identified the period when the program was at full operation (total enrollment 3 SWSW Business Case for Public Sector Investment - October 2010 at 1,000 or greater) and calculated the costs for this period. The second set of columns shows the estimated cost of the full operations period. At full operations, the $17.1 million of health coverage is an even larger share of total costs at 86 percent of the total $19.8 million. The cost of all other navigation and employment related elements totals $2.5 million, or $124.46 PMPM, substantially less (40%) than the PMPM cost of the full Demonstration period. We will use the $124.46 PMPM costs for navigation and employment services to calculate the costs of the program. The costs of reinsurance are not included, as it was purchased because the insured group was small and its cost history not well understood; reinsurance would not be needed for a larger group. We exclude the cost of health care services because most low income working adults will have some form of mandated coverage beginning in 2014. States or employers and participants will be incurring the costs of providing health care coverage for virtually all potential participants. At that time, the only consideration for states and the federal government will be the value of providing navigation and related services to supplement and foster optimal use of health care coverage. Considering the Costs of Comprehensive Medical Benefits It is important to note that Minnesota’s Medicaid program is quite comprehensive, as its state plan includes most optional Medicaid services. Comprehensive medical and mental health benefits were a critical element of the SWSW program; individuals needed access to affordable psychotropic medications, as well as treatment for co-occurring conditions such as substance abuse, back problems, surgeries, and dental care. This medical care was critical in allowing them to address health problems that otherwise limited their ability to work. States with more limited Medicaid benefits will need to consider the value of offering navigation and employment, and will also have to calculate the costs of offering a more comprehensive Medicaid benefit. 4 Benefits of SWSW SWSW has produced significant value to state and federal funders. Many of these benefits accrued over a period of years. This section describes the value of the benefits and calculates the total benefits to the public that can be reasonably estimated. Increased Independence The purpose of navigation services for SWSW participants was to increase independence through the improved use of health care benefits and other community resources, and an increased focus on attaining employment goals using needed employment supports. The intervention did reduce dependency on government income support programs. Reduced applications for disability benefits. According to participant self report, the intervention group applied for disability at a rate 9.5 percent lower than the control group, which was statistically significant. This means that 170 of the 1,794 SWSW participants who would have applied for disability did not do so. Federal disability benefits consist of Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), which is available to people who have contributed enough in Social Security withholding taxes. Those with lower earnings may also qualify for Supplemental Security Income (SSI). Minnesota also provides Supplemental Aid (MSA) for some SSI recipients. On a yearly basis, an SSDI recipient would receive approximately $13,500, and an SSDI/SSI recipient also getting Minnesota MSA would receive close to $10,000 annually. Disability status also provides eligibility for health coverage. SSDI participants qualify for Medicare coverage after 2 years on SSDI. SSI recipients qualify immediately for Medicaid. Clearly, the cost savings from preventing people from applying for disability are considerable. However, not all of those who apply for disability are determined eligible. In Minnesota, approximately half of applicants apply for SSDI and the other half apply for both SSDI and SSI. But only half of those www.staywellstayworking.com SWSW Business Case for Public Sector Investment - October 2010 applying for SSDI are determined eligible, and only about a quarter of those applying for both SSDI and SSI are determined eligible. Just over a third of those determined eligible for SSDI and SSI also get MSA. People who successfully apply for SSDI or SSDI/SSI are likely not to be working or to cease working when their income support and health care coverage begin. This means that they are no longer paying payroll taxes and federal and state income tax payments are likely to decrease. We can estimate the payroll tax payments that would be made by individuals who did not apply for SSDI because of SWSW services and supports. SWSW participants had an average monthly income of $1,574, amounting to $18,888 annually. Employees and employers each pay 7.65 percent in payroll taxes for Social Security and Medicare, amounting to a combined annual total of $2,890. Decreased use of other income support services. Approximately 20 percent of the intervention and control groups participated in Minnesota General Assistance and in SNAP (the Food Stamp program) at the time of the baseline survey (Table 2). Smaller percentages used housing subsidies, vocational rehabilitation, or other public programs. Both groups showed decreases in their use of Food Stamps and General Assistance between the first and second year surveys. The intervention group experienced significantly larger decreases. However, the differences between intervention and control were relatively small particularly for Food Stamps. Therefore, relatively few of the intervention group members who ceased to participate in General Assistance (27 individuals or 1.2%) or Food Stamps (2 individuals or 0.1%) could attribute the change to their participation in SWSW. The value of General Assistance for a year is approximately $2,300 and the value of 9 months of Food Stamps (the average for individual adults) is $760. Because of the effect size, the monetary benefits of reduced General Assistance and Food Stamps are relatively small. Table 2: Estimated Reduction in Public Program Participation N^ Formula Baseline 12 month B. % C. # D. % E. % F. Percent Change Between Baseline & 12 month Participation (C-E)/C G. Difference Between Intervention & Control F. Intervention – F. Control H. Percent Decrease Due to SWSW FxB Intervention Food Stamps Intervention 1,112 21.00% 234 16.50% 183 21.80%* Control 251 26.30% 66 20.70% 52 21.21% 0.59% 0.12% General Assistance Intervention 1,102 20.10% 221 8.20% 90 59.30%* Control 247 24.30% 60 11.30% 28 53.30%* 6.00% 1.20% * difference between baseline and 12 month is statistically significant at the 5 percent level (Sign Test); ^excludes missing responses; Source: Minnesota Demonstration to Maintain Independence and Employment: Evaluation Report – Phase 1. Estimating the Return on Investment To provide an estimate of the return on investment of SWSW’s navigation and employment related services, we estimated the costs and benefits of serving a cohort of www.staywellstayworking.com 3,000 participants, the approximate number that would be eligible and interested if the program was offered statewide in Minnesota. The first year costs are recouped (in present 5 SWSW Business Case for Public Sector Investment - October 2010 dollars) during the third year post program enrollment, and a savings equivalent to 45 percent of the initial investment is generated in the fourth year (net public costs).17 As shown in Table 3, provision of navigation and employment supports in conjunction with health care coverage to a cohort of 3,000 participants would prevent 285 applications for disability, of which 69 would have been accepted for SSDI, 38 would have been accepted for SSDI/SSI, and 3 would have ended their participation in Food Stamps. An additional 13.5 of those on SSDI/SSI would have received Minnesota Supplemental Aid. In addition, 36 participants would have ended their participation in General Assistance. Table 3: Reduction in Dependence in a SWSW Cohort of 3,000 Total enrollment 3,000 Prevented SSDI/SSI applications 285 Prevented SSDI enrollments 69 Prevented SSDI/SSI enrollments 38 Decrease in Food Stamp participation 3 Prevented MSA enrollments Decrease in GA participation 13.5 36 Source: Minnesota Demonstration to Maintain Independence and Employment: Evaluation Report – Phase 1 and SSA special report on Minnesota applications for SSDI and SSI 9/29/2010 To project net savings, we estimated total annual operating costs of $4.5 million to provide navigation and related employment services for a cohort of 3,000 for 12 months in 2008 dollars, assuming the program is at full operations (Table 4). Most of the monetary benefits accrue to the Social Security trust fund, which supports SSDI and Medicare. Other savings accrue to SSI and smaller support programs. Unlike 6 SSDI and SSI, eligibility for Food Stamps and General Assistance changes frequently, and average tenure is limited. We therefore cannot assume that the savings achieved in one year will continue at the same rate in following years. Total savings are discounted using the Social Security Administrations intermediate assumptions for the real rate of return on trust fund dollars (investment rate less inflation rate). www.staywellstayworking.com SWSW Business Case for Public Sector Investment - October 2010 Table 4: Estimated Return on Investment of Navigation and Related Services for a Cohort of 3,000 at Full Operations 2008 Total Annual Operating Costs 2009 2010 2011 2012 $4,480,448 SSDI Savings $931,914 $931,914 $943,097 $965,731 SSDI/SSI Savings (2009) $332,305 $332,305 $336,293 $344,364 Payroll Tax Payments $309,215 $309,215 $309,215 $309,215 $1,573,434 $1,588,605 $1,619,310 $16,196 $17,161 Food Stamp Savings $327 Total Federal Savings $1,573,761 MSA Savings $15,254 $15,722 GA Savings $85,199 $24,365 Total State $100,453 $40,087 $16,196 $17,161 $1,674,214 $1,613,521 $1,604,801 $1,636,471 $1,599,129 $1,577,975 $1,632,879 $1,207,105 +$370,870 +$2,003,749 Total Overall Savings Present Value Net Public Cost $4,480,448 $2,806,234 Source: Social Security Administration, Disabled Beneficiaries and Dependents Master Beneficiary Record file and Supplemental Security Record file, 100 percent data, 2008; Minnesota Department of Human Services, Reports and Forecasts Division, Family Self-Sufficiency and Health Care Program Statistics, June 2010; Special Report on Minnesota Food Stamp tenure, 10/14.2010; 2010 OASDI Trustees Report. Limitations. Analyses are based on selfreported rates of SSI/SSDI applications. In addition, analyses assume that the individuals whose SSDI applications were prevented continue to be able to maintain employment and independence for at least the four years of the analysis. If some only postpone their application for a year or two, savings estimates would be reduced. The limited length of the Demonstration did not provide the information necessary to understand the durability of the positive effects generated by the program. Given the time required to generate a return on the investment, it is important to better understand longer term impacts of the intervention. By design, this return on investment model is conservative and does not include certain potential savings, nor does it assume the additional state or federal income taxes that people would pay when they continue to work rather than depend on SSDI or SSI. In addition, we have not attempted to determine whether there would be savings in health care coverage. However, the following section discusses the possibility that SWSW services may desirably affect health care costs over the long run. www.staywellstayworking.com Costs of SWSW Participants’ Health Care SWSW participants, all of whom had an identified mental health problem, had lower health care costs on average than estimated for their member per month rate. This was true even though SWSW participants, as described below, increased their utilization of dental, pharmacy, and medical services in comparison to the year before SWSW enrollment and in comparison to the control group. In addition to demonstrating increased access to medical care, SWSW participants also reported participation in preventive care and behavior changes, like quitting smoking that could generate longer term savings in use of high cost services. Utilization. Intervention group members increased their utilization of health care services in all categories compared to the 12 months before enrollment in SWSW. Control group participants reduced their health care utilization in comparison to the prior year. The intervention group’s pattern of increased utilization continued in the second year for those who remained in the program. 7 SWSW Business Case for Public Sector Investment - October 2010 Preventive care. The intervention group had a statistically significant higher rate of reporting a wide variety of health screens. The most widely used screens were for Well Woman exams, dental exams, eye exams and mammograms. Continuity of prescription. The control group was more likely to use strategies for managing the cost of prescriptions such as participating in a pharmacy assistance program or not filling some prescriptions. Most prescriptions were prescribed by participants’ primary care providers. Healthy behaviors. Thirteen percent of the intervention group reported that they had quit smoking. employees, increased their value, or resulted in a better job. The evaluation measured participants’ self-reported employment and income changes. Many of these changes would have also benefitted their employers in concrete and measurable ways, though we do not have data to quantify it. SWSW participants successfully met employment goals: Participants who completed an annual review with their navigator and set employment related goals reported meeting almost half (49%) of those goals. Nearly three-quarters of those who wanted to maintain their current job met their goal and 33 percent of participants who made a goal to find a better job were successful. Reduced medical debt. There is a considerable and statistically significant difference in the percentage of intervention and control group members that carry medical debt. At the end of the second year, 17 percent of the intervention group reported carrying medical debt, while almost half (48%) of the control group did so. Worry about incurring or increasing medical debt can cause people to postpone or forego needed medical care. Participants set a variety of other goals, including: Good preventive and primary care practices, such as those described above, can reduce the use of high cost emergency room and inpatient services by maintaining good health and managing chronic health conditions.18 However, the savings from reduced use of high cost services may be realized over a period of years. While Minnesota’s cost did not change because they paid a capitated monthly fee to Medica, states should be able to realize longterm savings from reduced utilization of high cost services. These savings can be immediately captured in state fee for service Medicaid, and will eventually affect capitation payments. SWSW participants with greater functional impairments demonstrated a significant increase in earnings. In the first year, both the intervention and control group members maintained or improved their income. However, some members of the intervention group showed statistically significant increases in income in comparison to their control group counterparts. Benefits to Participants and Employers SWSW participants set and reached a number of goals that maintained their value as 8 • Maintain current job; • Improve work/professional skills; • Improve attendance at work; • Meet productivity goals; • Improve salary/increase hours; and • Improve attitude at work and co-worker relations. Individuals in the intervention group with lower Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF <50)19 reported higher earnings at 12 months, while control group participants with lower GAF scores reported a significant decrease of nearly $5,000 in their earnings after a year. This placed them well below the poverty line and at greater risk of losing independence, offering a strong rationale for targeting this group for navigation and employment supports. www.staywellstayworking.com SWSW Business Case for Public Sector Investment - October 2010 Participants more engaged in the program experienced greater gains in earnings. Within the intervention group, more engaged participants experienced greater increases in earnings one year after enrollment compared to participants who were less engaged (7% v. 2%). They also showed significant improvements in mental health status and overall functioning. Participants with higher engagement were those who had ten or more navigator contacts annually and completed an annual review of their goals. Earnings increased with greater time in SWSW. While both groups reported increased earnings over time, the increase at 24 months was only statistically significant for the intervention group. Intervention group participants enrolled in SWSW for at least 24 months reported an average earnings increase of 14 percent compared to an increase of 8 percent for control group participants. Personal Benefits for SWSW Participants Improvements in financial status and quality of life. Intervention group participants reported statistically significant improvements in their ability to afford food, housing, clothing, travel around the city and social activities which the control group did not experience. The intervention group also reported statistically significant increases in positive feelings about seven aspects of quality of life, including financial situation, work and salary, social life, living arrangements, free time, health, and life in general, while control group members experienced increases in only two aspects. Conclusion Analyses presented in this brief show that the Stay Well, Stay Working program could yield a significant return on public investment in less than four years based on an estimated potential savings from reduced dependence on public programs. Most of the return is realized by the Social Security system, demonstrating a strong incentive for the Social Security Administration to invest in this kind of program. While this www.staywellstayworking.com analysis shows relatively small effects on other public programs such as General Assistance and Food Stamps, targeting services on the lower functioning individuals in this group is likely to show a larger impact. Many participants generated increased earnings, especially those with more severe problems and those who were more engaged in the program. This would have generated greater income tax revenue. Almost all participants set employment related goals, and met many of them, even in a challenging economy. Their accomplishments often benefitted their employers in the form of higher productivity, more consistent attendance and better employee relations. Depression and anxiety were the most common problems for the individuals in the SWSW program, and are also the conditions of highest prevalence among employees overall. The SWSW navigation model could become an important addition to employer options for addressing problems of workers with more serious mental health conditions. Additional benefits that participants received include greater independence and ability to use community resources, greater health and job satisfaction, reduction in medical debt, and greater satisfaction in multiple life dimensions. Author Information This research brief was a joint collaboration of The Lewin Group and DMA Health Strategies. Author collaborators included Karen W. Linkins, PhD, Jennifer J. Brya, MA, MPP, Wendy Holt, MA, and Richard Dougherty, PhD. The sum of years of potential life lost due to premature mortality and the years of productive life lost due to disability. 2 Chisholm, D., Saxena, S. and van Ommeren, M. (2006) Economic Aspects of Mental Health: Key messages to health planners and policy-makers, Chapter 2: Burden of Mental and Behavioral Disorders, World Health Organization. 3 Ibid. 4 Aumann, K. and Galinsky, E., (2008) The State of Health in the American Workforce: Does Having an Effective Workplace Matter?, National Study of the Changing Workforce. Families and Work Institute, 2009. 1 9 SWSW Business Case for Public Sector Investment - October 2010 Stewart, W.F., Ricci, J.A., Chee, E., Hahn, S.R., and Morganstein, D. (2003) Cost of Lost Productive Work Time Among US Workers with Depression, JAMA, 289:23. 6 Toran, M. Making Mental Connections, Risk & Insurance Magazine, LRP Publications, May 2005. 7 Kessler, R., White, L., Birnbaum, H., Qiu, Y., Kidolezi, Y., Mallett, D., Swindle, R. (July 2008) Comparative and Interactive Effects of Depression Relative to Other Health Problems on Work Performance in the Workforce of a Large Employer, JOEM, 60:7. 8 Warren, P.A. (2005) The Management of Workplace Mental Health Issues and Appropriate Disability Prevention Strategies,Work Loss Data Institute, pp. 6-7. 9 Langlieb, A.M., Kahn, J.P. “How Much Does Quality mental Health Care Profit Employers?”, JOEM, Vol. 47, No. 11, Nov. 2005. 10 Drake, R.E., Skinner, J.S., Bond, G.R., and Goldman, H.H., (2009) Social Security and Mental Illness: Reducing Disability with Supported Employment. Health Affairs, 28, no.3:761-770. 11 Annual Statistical Report on the Social Security Disability Insurance Program, Social Security Administration, 2009. 12 SSI Annual Statistical Report, 2008, Social Security Administration. 13 Richard Csiernik, David Hannah, and James Pender. 2006, “A Review of the University of Saskatchewan Employee Assistance Program.” Report to the University of Saskatchewan. Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. 14 Campbell, TL; Franks, P; Fiscella, K; McDaniel, SH; Zwanziger, J; Mooney, C; Sorbero, M; Do Physicians 5 10 Who Diagnose More Mental Health Disorders Generate Lower Health Care Costs? Journal of Family Practice, Vol. 49, No. 4, April 2000. 15 American Psychiatric Association, Early Treatment for Employees Increases Productivity, Mental Health Works, Third Quarter 2003. 16 For additional detail on cost components, see the Appendix to the SWSW Manual. 17 For the purposes of this estimation, we have assumed that the cohort was served in 2008 and benefits were accrued beginning in 2009. This allows us to use actual SWSW cost data and results, and actual data on costs of public benefits for 2008 and 2009. Official Social Security and State of Minnesota projections are used for public program costs in the years 2010 and 2011. However, our analysis is done in the context of the 2014 provisions of health reform, and therefore assumes that SWSW services are provided as a supplement to health care coverage which is not an optional expense. 18 The Partnership for Medicaid, Reducing Inappropriate Emergency Room Use among Medicaid Recipients By Linking Them to a Regular Source of Care. Available online <http://www.thepartnershipformedicaid.org/images/ upload/ER_Use.pdf>, Accessed 10/29/2010. 19 Functioning was measured using the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale in the Diagnostic Statistical Manual IV (DSM IV), which was administered as part of the eligibility determination process for the SWSW program. Individuals with a GAF score lower than 50 are classified in the DSM-IV as having “serious impairment in social, occupational and school functioning (e.g., limited social supports, unable to keep a job). www.staywellstayworking.com