The Application of Anti-Corrosion Coating for Preserving the Value

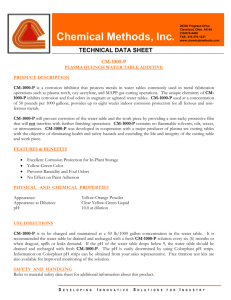

advertisement