Measuring Economic Value in Cultural Institutions

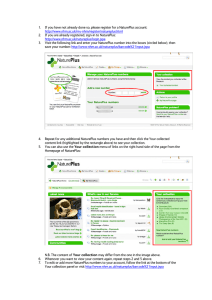

advertisement