AC/DC/AC PWM converter with reduced energy storage in the DC link

advertisement

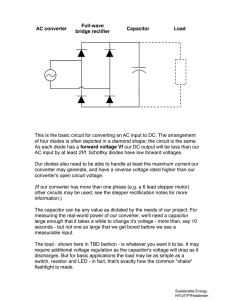

IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON INDUSTRY APPLICATIONS, VOL. 31, NO. 2, MARCWAPRIL 1995 281 AC/DC/AC PWM Converter with Reduced Energy Storage in the DC Link Luigi Malesani, Fellow, ZEEE, Leopoldo Rossetto, Paolo Tenti, Senior Member, ZEEE, and Paolo Tomasin Abstract- The paper introduces the family of quasi-direct converters, i.e., forced-commutated adddac converters including small energy storage devices in the dc link. In particular, the case of three-phaseto three-phasequasi-directconverter is considered. Since energy storage minimization calls for instantaneous inputloutput power balance, a proper control strategy is needed. The paper describes a simple and effective control technique which also provides high-power factor and small distortion of the supply currents. After a discussion of the general properties of quasi-direct converters, design criteria of both power and control sections are given, and experimental results of a 2-kVA prototype are reported. I. INTRODUCTION M ATRIX converters, originally introduced in [ 11, have received considerable attention [2]-[4] due to their potentiality to provide direct aclac conversion without energy storage. However, they never tumed into wide application due to severe requirements: four-quadrant switches, critical timing, sensing of switch voltage and current, snubber circuits needed to absorb overvoltages coming from the inductive commutation. As a result, circuit efficiency and reliability are affected. More popular is the indirect acldclac conversion by means of PWM rectifier-inverter systems with dc voltage link. As compared to matrix converters, these systems show improved reliability and allow a greater output voltage. In fact, they only call for unidirectional switches; moreover, a big tank capacitor in the dc link provides decoupling between the rectifier and the inverter, so that the two converters can be driven independently according to usual PWM techniques [ 5 ] , [6], providing excellent input and output performances. However, the tank capacitor can be a critical component, especially for high-power or high-voltage applications, since it is large, heavy, and expensive. Moreover, it is normally the prime factor of degradation of the system reliability. Quasi-direct converters are intermediate between the previous ones, since they include unidirectional switches and a small energy storage element. In particular, quasi-direct Paper IPCSD 9 4 7 0 , approved by the Industrial Power Converter Committee of the IEEE Industry Applications Society for presentation at the APEC '93 Eighth Annual Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition, San Diego, CA, March 7-1 1. Manuscript released for publication September 1, 1994. L. Malesani, L. Rossetto, and P. Tomasin are with the Department of Electrical Engineering, University of Padova, 35 131 Padova, Italy. P. Tenti is with the Department of Electronics and Informatics, University of Padova, 35 131 Padova, Italy. IEEE Log Number 9408 182. Fig. 1. Basic converter scheme. converters with dc voltage link have the same scheme as the corresponding indirect converter, but with a much smaller tank capacitor. A higher power density and improved reliability can therefore be obtained. Quasi-direct converters have the same output performances and component stresses as their indirect counterparts (which means power reversibility, no need for heavy snubbers, no critical timing, etc.), but, due to the small energy stored in the dc link, the input and output stages are coupled. Thus, inputloutput power balance must be ensured by the control, which must be fast and accurate. Another control task is to optimize the input performances, so as to obtain sinusoidal supply currents in phase with the line voltages. A control strategy able to meet all desired requirements is described hereafter. 11. PRINCIPLES OF OPERATION The basic converter configuration is shown in Fig. 1. It looks like an usual indirect converter including two fullbridges converters and a tank capacitor in the dc link. Owing to the scheme symmetry, bidirectional power control is possible. The left-side (input) bridge, connected to the supply line, is operated so as to absorb sinusoidal currents in phase with the line voltages. The right-side (output) bridge, feeding the load, is controlled to produce proper load voltages and currents. Both bridges are controlled by a PWM technique in order to obtain accurate waveform shaping and fast dynamic response. 0093-9994/95$04.00 0 1995 IEEE 288 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON INDUSTRY APPLICATIONS, VOL. 31, NO. 2, MARCWAPRIL 1995 The tank capacitor stores the amount of energy needed to keep the dc voltage ripple below a suitable limit, while input converter control keeps constant the dc voltage. As our goal is to minimize the tank capacitor, the input converter must provide fast control of the energy exchange between line and storage capacitor. In fact, any inputloutput power unbalance causes a variation of the stored energy and, if the capacitor is small, the dc voltage may vary widely. In order to obtain fast response of the input converter, a proper current control technique (e.g., hysteretic) can be adopted, which keeps each line current close to its reference, ensuring good accuracy and small delay time. In any case, some dc voltage variations are unavoidable, but they should not affect the output performance. For this purpose, a suitable control technique must be adopted for the output converter [8]-[ 1 11. For instance, the current control technique described in [7], which is inherently insensitive to dc voltage variations, could be adopted for both input and output bridges. 111. INPUT CONVERTER CONTROL As mentioned above, input converter control is aimed at maintaining a constant dc link voltage irrespective of the current absorbed by the output stage. Moreover, a high-power factor must be ensured, which calls for sinusoidal, in-phase line currents. For this purpose, as shown in Fig. 1, the input current references are produced by adjusting the amplitude I/* of three sinusoidal and symmetrical waveforms, in phase with the line voltages. Line current amplitude 1’* results from the inputloutput power balance; in fact, in the steady state, given output power Po the average current I: absorbed by the output converter is: Current reference amplitude I/* can therefore be calculated directly from the value of I:, which is the dc component of current i$ absorbed by the output converter. Accordingly, in the scheme of Fig. 1, current :i is low-pass filtered to obtain average value I:, which is then multiplied by coefficient K to provide reference signal I;. However, if K changes, due to working point variations, the input/output power balance cannot be ensured and the link voltage varies. In order to keep constant link voltage U d , irrespective of reference and load variations, a closed-loop control is introduced: Voltage U d is compared with reference U:, and is fed to a PI regulator, which the resulting error signal provides correcting term I p , also shown in Fig. 1. This term is added to I; to obtain input current reference amplitude I / * . In theory, the voltage control loop could work alone. However, sensing current 2; ensures a feed-forward action which speeds up the response. In our implementation, the input current references are obtained from a look-up table in which the samples of three sinusoidal and symmetrical waveforms are stored. Then, a multiplying digital-to-analog converter converts these values in the analog ones (iy, ig, 2:) with the amplitude I/*. A PLL is used to synchronize the current references with the line voltages. It keeps to zero the sum of the three phase current displacements, each given by an independent phase comparator. The PLL response is very slow, but this does not affect the system performance because the line frequency remains almost constant. The pull-in time of the PLL is included in the converter start-up time. I v . DYNAMIC RESPONSE The size of the tank capacitor is heavily affected by the dynamic response of the dc voltage control loop. In fact, where u d is dc link voltage and 772 is output converter in presence of load transients, the capacitor energy changes efficiency. Converter input power is: according to the power unbalances occumng during the control settling time, and the capacitor must be sized in order to limit the corresponding dc voltage variations. The speed of response of the input converter is limited by where I: and 71 are average dc current and efficiency of the a low-pass filter in the current loop, which delays the feedinput converter, respectively, while U’ and I’ are the rms forward action, and by the PI regulator, which determines the bandwidth of the voltage loop. values of the line voltage and current. Consider in general that a fast voltage loop allows a From ( 2 ) , assuming equal values for I: and I:, we obtain: reduction of the energy exchange and, consequently, of the capacitor size. On the other hand, it tends to modulate the (3) input current amplitude, producing a distortion which affects which shows that line current amplitude is proportional to the power factor. In order to optimize the control parameters, let us first current I: by a term which depends on the working point. Assuming, in a first instance, a fixed working point, we have analyze the system dynamic. A suitable model is given by the block scheme of Fig. 2, which is obtained by linearizing that term: (1)-(3) around the working point, assuming unity the efficien71 and 772. From this model, capacitor current variation cies (4) AI, can be evaluated from, the corresponding variations of variables Ud, I:, I f and I p . The scheme shows the feedis constant, so that (3) becomes: forward path ( a ) ,which corrects the input current amplitude according to the output power variation AI‘,, together with ~ MALESANI et al.: AC/DC/AC PWM CONVERTER WITH REDUCED ENERGY STORAGE IN THE DC LINK where T2 is a function of the working point, T is the time constant of the PI regulator, and K1 represents the total loop gain. K1 and T determine the system response and can be optimized by a proper design of the PI regulator. For stability computations, the delay related to the converter switching frequency must also be taken into account. If line voltage U' or link voltage U d differ from their nominal value, (7) is no more valid because of a certain amount of detuning in loop y. This situation only occurs during wide load transients and cannot be analyzed by means of the smallsignal model described above. However, simulation done for various converter parameters demonstrated that the system detuning does not affect heavily the control dynamic. This was also experimentally verified, as it will be shown in the experimental results section. Y I 289 V. CONVERTER DESIGN I A. Power Section Fig. 2. Small signal block scheme. several feedback paths (p, y, and S), each accounting for different effects of dc voltage variation AUd. As capacitor current I , is the difference beetwen current I: and I;, the variations of these latter variables can be considered separately. Differentiating (1) we obtain: The first term, which corresponds to the input block of Fig. 2, accounts for the current taken from the tank capacitor due to a load power variation. Instead, the second term accounts for the current change due to a dc voltage variation. This latter term corresponds to loop p and shows a positive feedback, which may cause stability problems (for constant output power, if capacitor voltage U, decreases then output current 1; must increase, causing an additional reduction of the capacitor voltage). Feedback path y is related to the feed-forward action. It compensates (totally or partially) for positive feedback p, producing a variation of the capacitor current AI, which is opposite to that caused by p. If K is perfectly tuned the dotted box in Fig. 2 has unity gain and, assuming that the low-pass filter has also unity gain within the band of the control loop, the effects of feedback paths /? and y compensate each other. Moreover, the resulting open-loop gain becomes independent of output power variation AP,. The last feedback path (6)accounts for the PI compensation, which produces the correcting term I;, described above, and must be designed ito assume fast and stable converter response. In the hypothesis of correctly tuned feedback path y, the open-loop gain of the voltage control loop is: (7) The power semiconductors are selected as for a standard voltage-fed half-bridge inverter. The only difference is that dc link voltage can vary more than usual, calling for a suitable voltage margin. The input inductances, given switch type and modulation frequency, are designed to suit current ripple requirements. The tank capacitor must be designed taking into account that: the voltage ripple is due to the high-frequency components of the modulated dc currents of both converters; if all switches are tumed off, inductors energy flow in the capacitor, increasing its voltage; during the delay time of the voltage control loop, the output power demand must be sustained by the tank capacitor energy. It is easy to verify that the first two conditions are less critical than the third, which determines the capacitor size. The same condition determines the capacitor size also in the case of standard indirect converters: These latter, however, have longer response times due to the need of decoupling the input and output stages, thus calling for bigger capacitors. Given response time T,. of the voltage control loop, which is limited by the switching frequency, and maximum expected variation of the output power AP,,,, the energy AWd exchanged by the tank capacitor can be estimated as: m A T I L from which the dc voltage variation results: (9) Given the maximum allowed dc link voltage variation AU,,,, the value of Cd tums out to be: In this equation, response time T,. also accounts for the modulation delay of the input converter, which is related to its 290 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON INDUSTRY APPLICATIONS, VOL. 31, NO. 2, MARCWAPRIL 1995 switching frequency. In practice, T, is in the order of a few modulation periods. B. Control Section The design can be done according to (4) and (7). Given the switch modulation frequency, delay time T, is estimated first. Then, control bandwidth and PI regulator parameters are easily derived. As mentioned above, the low-pass filter must have unity gain in the frequency band of the control loop, while it must have reduced gain at the modulation frequency, so as to avoid high-frequency noise on input current reference I t * .Therefore, the filter bandwidth is designed equal to the control bandwidth, its order resulting from the desired attenuation at the switching frequency. In our implementation a third-order low-pass filter was employed. The bandwidths of the current and voltage sensors and of the reference generator do not affect the system stability, since they are normally wider than the control bandwidth. VI. EFFECTSOF VOLTAGE LOAD UNSYMMETRY UNBALANCE AND For the capacitor design, the presence of unbalanced line voltages or unsymmetrical load impedances must be taken into account carefully. In both cases, in fact, since control enforces sinusoidal and symmetrical line currents, the instantaneous input/output power balance cannot be satisfied. Thus, for a constant amplitude of the current references, low-frequency fluctuations may appear in the capacitor voltage. This can be faced by increasing the response speed of the voltage loop, causing a modulation of the input currents amplitude. As a consequence, some distortion on the line currents may appear and the total power factor is affected. This effect is common to all converters with reduced energy storage, in particular to matrix converters. It can be overcome by more sophisticated control strategies, like that described in [ 121, able to maintain a high-power factor irrespective of unbalances and unsymmetries. Some distortion is unavoidable however. In practice, line voltage unbalances usually cause small dc voltage variations, as compared to those caused by large load power steps. Instead, large load unsymmetries may cause considerable power fluctuations, affecting the capacitor design. VII. EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS The actual operation of a quasi-direct converter was tested on a small prototype, designed according to the above criteria. Converter ratings are: Output power: Supply voltage: dc link voltage: Output voltage: Rated output current: Switching frequency: Line inductance: Tank capacitor: 2 kVA 150 V rms, 50 Hz (line-to-line) 300 V 0 + 150 V rms, 0 + 100 Hz 7.5 A rms 5 kHz (IGBT switches) 3.5 mH 601160 pF. 0 Fig. 3. ms 100 Step load response for Cd = 60 jiF, Two different values for capacitor c d were tested. The first (60 pF) was designed to provide a d c voltage ripple in the steady state equal to 5% of the rated voltage. The second (160 pF) was designed according to (10) in order to achieve a 10% dc voltage variation in the case of full-power load step. The control delay T,. was selected at about 1 ms (five modulation periods). In the practical implementation, tank capacitor Cd has been split in smaller capacitors, each connected across one inverter leg. In this way the high-frequency filtering action is improved (stray inductances are minimized) and nonelectrolytic capacitors can be employed. Experimental results with the first capacitor are given in Fig. 3, showing the system response to a sudden load variation. In particular this figure shows: input current amplitude reference I t * , input line current it, load current i” (at 63 Hz) and link voltage u d . The load changes (transitions from noload to full-load and vice versa) are quickly compensated by the voltage control loop, but wide variations of dc voltage u d (up to 70 v ) occur due to the large power step. Due to these variations, the dc link voltage was kept below the rated value. The voltage ripple at full-load results from load and line unbalances and, as explained above, slightly affects the input current waveforms. An input power reversal occurs when opening the load (signal 1’* becomes negative), so as to extract the energy in excess from the tank capacitor. Fig. 4 shows the same converter waveforms with a 160-pF tank capacitor. The dc voltage variation remains within the desired limits, while the settling time is about the same as in the previous case. ~ MALESANI et al.: ACIDCIAC PWM CONVERTER WITH REDUCED ENERGY STORAGE IN THE DC LINK 291 325 300 275 ms 0 Fig. 4. Step load response for c d 100 = 160 pF. In the same conditions of Fig. 3, Fig. 5 shows the behavior of signals I p , If,I’* together with line current i’. Fig. 5 shows that signal I; (output of the PI regulator) is near zero in the steady state. This implies that feed-forward term If ensures correct input/output power balance, coefficient K being selected according to (4) (zeroing of 1; can be used for control tuning). During transients, because of the changes in U& the gain of the dotted line block of Fig. 2 differs from unity, thus detuning the feed-forward control, which does not ensure the input/output power balance. However the closed-loop voltage control adjusts the input current amplitude rapidly, without any dynamic instability. Lastly, Fig. 6 shows the input behavior at full load in the steady state. The line current results in phase with the supply voltage and a good power factor (0.98) is obtained, in spite of the considerable voltage distortion. VIII. CONCLUSIONS Quasi-direct converters have been discussed, which are characterized by circuit complexity and load performances similar to those of indirect ac/dc/ac converters, but require only a small energy storage in the dc link. This condition calls for instantaneous input/output power balance, which must be provided by the control. Accordingly, input performances become similar to those of matrix converters, but control is much simpler and a greater output voltage can be achieved. Morevover, four-quadrant switches are not needed. Due to the significant reduction of energy storage capacitors, quasi-direct converters are inherently smaller and cheaper than Fig. 5. Step load response for c d = ms 0 Fig. 6. 60 pF. 100 Input converter behavior. conventional solutions, and capable of higher power density and improved reliability. ACKNOWLEDGMENT The authors would like to thank Dr. S. Baggio for the experimental activity and R. Sartorello for his helpful suggestions on converter implementation. REFERENCES [ I ] M. Venturini, “A new sine wave in, sine wave out, conversion technique eliminates reactive elements,” in Powercon 7, San Diego, CA, 1980, pp. E3-El5. [2] J. Oyama and T. Higuchi er al., “Novel control strategy for matrix converter,” pp. 36CL367. [3] G. Roy and G. E. Apr., “Cycloconverter operation under a new scalar control algorithm,” Ibidem,pp. 368-375. 292 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON INDUSTRY APPLICATIONS, VOL. 31. NO. 2, MARCHIAPRIL 1995 [4] P. Tenti, L. Malesani, and L. Rossetto, “Optimum control of N-input K-output matrix converters,” IEEE Trans. Power Elecfron., vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 707-713, Oct. 1992. [5] D. Divan, T. Habetler, and T. Lipo, “PWM techniques for voltage source inverters,” IEEE-PESC, 1990, Tutorial Notes. [6] R. Wu, S. Dewan, and G. Slemon, “Analysis of an ac to dc voltage source converter using PWM with phase and amplitude control,” in IEEE Ind. Applicaf. Soc. Annu. Meefing, San Diego, CA, Oct. 1989, pp. 1156-1 163. [7] L. Malesani and P. Tenti, “A novel hysteresis control method of current controlled VSI PWM inverters with constant modulation frequency,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Applicat., vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 88-92, 1990. [SI H. W. Van Der Broeck, H. C. Skudelny, and G. Stanke, “Analysis and realization of a pulse width modulator based on voltage space vectors,” in IEEE-IAS 86, Denver, CO, Sept. 1986, pp. 244-251. [9] S. Ogasawara, H. Akagi, and A. Nabae, “A novel PWM scheme of voltage source inverters based on space vector theory,” in EPE 89, Aachen, Germany, pp. 1197-1202, Oct. 1989. (IO] S. Fukuda, Y. Iwaji, and H. Hasegawa, “PWM technique for inverter with sinusoidal output current,” IEEE Trans. Power Electron., vol. 5 , no. I , pp. 5 4 4 1 , Jan. 1990. [l 11 D. M. Brod and D. W. Novotny, “Current control of VSIPWM inverters,” IEEE Trans. Znd. Applicaf., vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 562-570, 1985. [12] D. Ciscato, L. Malesani, L. Storari, L. Rossetto, P. Tenti, G. L. Basile, and F. Voelker, “Optimum control of PWM rectifiers for magnet supply,” in 4th European Conj on Power Electron. and Applicaf. (EPE 91), Firenze, Italy, Sept. 1991, vol. 2, pp. 0 8 9 4 9 4 . Luigi Malesani (M’63-SM’93-F’94), for a photograph and biography, please see page 279 of this issue. Leopoldo Rossetto, for a photograph and biography, please see page 279 of this -issue. Paolo Ten1 :M’85-SM’91), for a photogrq and biomar, 1 . F ase see page 279 of this issue Paolo Tomasin was bom in Cittadella (Padova), Italy. He received the degree with honors in electronics engineering from the University of Padova, in 1989. In 1993, he received the Ph.D. degree in informatics and industrial electronics at the University of Padova. Since 1994, he has been working at the RPM, Rovigo, Italy, a company that is involved with production of induction motors for the development of ac motors and ac motor drives. His main interests are in the fields of ac motor drives and soft-switching converters.