Global trends in contraceptive method mix and implications for

advertisement

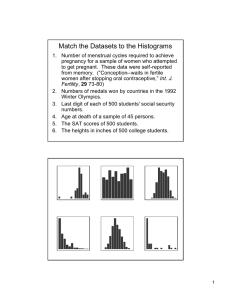

Global trends in contraceptive method mix and implications for meeting the demand for family planning Ann Biddlecom and Vladimira Kantorova United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division 19 August 2013 PRELIMINARY DRAFT Corresponding author: Ann Biddlecom, United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, New York, NY 10044 (email: biddlecom@un.org). Paper to be presented in Session #013 “Sexuality and reproductive health”, XXVII IUSSP International Population Conference (Busan, Republic of Korea). The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations. Abstract Measuring progress in meeting the demand for family planning requires not only attention to levels and trends in contraceptive prevalence and unmet need for family planning but also assessment of the diversity of contraceptive methods used. We examine changes in contraceptive method mix from 1990 to 2011 for 188 countries and if trends in contraceptive prevalence are associated with the average effectiveness and concentration of methods used. We use annual Bayesian hierarchical model-based estimates of contraceptive prevalence and unmet need for family planning among married or in-union women aged 15-49 and apply the distribution of contraceptive users by method used from surveys at two time points (around 1990 and 2011). Female sterilization and the IUD were the two most common methods used worldwide and geographical differences in method mix profiles were large. Shifts were gradual over the past two decades in the distribution of users by method and average effectiveness. The evidence does not suggest an association between increases in contraceptive prevalence and improvements towards a more balanced or effective method mix. We propose a measure of the effectiveness of contraceptive demand—one that incorporates unmet need for family planning—as a useful summary measure to describe improvements in meeting the demand for family planning. 2 Introduction The past twenty years have witnessed significant progress in meeting the demand for family planning. Worldwide contraceptive prevalence has risen among women of reproductive age who are married or in a cohabiting union from 54.8 per cent (95 per cent uncertainty interval 52.3–57.1) in 1990 to 63.3 per cent (60.4–66.0) in 2010, or 8.5 percentage points (4.7–12.1) (Alkema et al. 2013). Most of the increase in contraceptive prevalence at the global, regional and country level that occurred between 1990 and 2010 was attributable to increases in the use of modern methods. Worldwide, 57.0 per cent (54.1–59.7) of married women of reproductive-age were using a modern method in 2010. The largest absolute increases from 1990 to 2010 in the use of modern methods (more than 15 percentage points) were in Central America, Eastern Europe, and three subregions of Africa (Eastern Africa, Northern Africa, and Southern Africa). In a similar manner, the percentage of women of reproductive age, either married or in a union, with an unmet need for family planning (i.e., women who want to stop or delay childbearing but are not using any method of contraception) decreased worldwide from 15.4 per cent (14·1–16·9) in 1990 to 12.3 per cent (10·9–13·9) in 2010, which was driven by decreases in developing countries. Yet measuring improvements in meeting the demand for family planning requires not only assessment of overall levels and trends in contraceptive prevalence and unmet need for family planning but also an assessment of the effectiveness and range of contraceptive methods used. A key objective of family planning programmes, emphasized in the Programme of Action of the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development, is to ensure that “…women and men have information and access to the widest possible range of safe and effective family-planning methods in order to enable them to exercise free and informed choice” (United Nations 1996). Of course, use of specific methods does not approximate access, but they are indeed related. Prior research has shown that as access to a range of modern contraceptive methods improves, modern contraceptive prevalence increases (Ross et al. 2001) and a high concentration of contraceptive use on one or two methods may be a sign of a limited range of available methods (Sullivan et al. 2006). 3 We provide updated estimates of the distribution of contraceptive users by method at two time points (1990 and 2011) for 188 countries or areas—one of the most comprehensive assessments to date—and examine the degree to which a rise in contraceptive prevalence over time is associated with increases in the average use-effectiveness and decreases in the concentration of methods used. We draw on different measures of the effectiveness and concentration of method mix to characterize global, regional and country level changes over time. Data and measures Analysis of family planning levels and trends is challenging because the number of survey-based observations per country is limited or often not timely. In a 2012 compilation of data on family planning indicators for 194 countries and areas, 60 per cent of countries and areas with data on contraceptive prevalence had less than five observations (United Nations 2012). Furthermore, differences in the survey design and implementation, as well as differences in the way survey questionnaires are formulated and administered can affect the comparability of data over time and between countries. To strengthen the comparability of our analysis of family planning levels and trends, we draw on Bayesian hierarchical model-based estimates of contraceptive prevalence (total, modern and traditional) and unmet need for family planning for 1990 and 2011 among women of reproductive age (15-49 years old) who are married or in a cohabiting union (see Alkema et al. 2013 for model details). To produce estimates of prevalence of specific methods, we used data on the distribution of contraceptive users by method from surveys covering nationally representative samples of married or in-union women of reproductive age. Methods were classified into 10 categories: female sterilization, male sterilization, the pill, injectables, implants, IUD, male condom, vaginal barrier methods, other modern methods and any traditional method (e.g., rhythm or withdrawal). Categorization is mutually exclusive with more effective methods receiving priority. Detailed data, including information on data sources and model-based country, regional and global estimates, are publicly available in a recent 4 United Nations Population Division data set on family planning indicators (United Nations 2012) and a 2013 update for monitoring progress on the target under Millennium Development Goal 5 to achieve universal access to reproductive health by 2015 (United Nations 2013). We applied survey-based observations on the distribution of contraceptive users by method at two time points, around 1990 (1983-1999) and around 2011 (2000-2012), to the model-based estimates of modern contraceptive prevalence in 1990 and 2011. We used the model-based estimates of traditional method prevalence and did not examine the distribution of specific traditional methods as emphasis in most family planning programmes and governmental health system initiatives is to expand access to effective methods of contraception rather than to promote less effective traditional methods. Moreover, the typical use-effectiveness of traditional methods is similar across the main traditional methods used. Data on the distribution of contraceptive users by method for the two time points were not available for 33 of 188 countries or areas (or 18 per cent): 17 are countries or areas in the Caribbean and Oceania with small population sizes, 9 are countries in Europe (or 26 per cent of the 35 countries in Europe with any data) and the remaining 7 countries (Equatorial Guinea, Israel, Libya, New Zealand, South Sudan, Turkmenistan and the United Arab Emirates) are spread across other regions (see appendix table 1). While the distribution of specific modern methods was held constant in these 33 cases, the percentages were applied to the model-based estimates of modern contraceptive prevalence in 1990 and 2011, which changes over time. Thus, the proportion of users by specific method will be the same over time in these cases but the percentage of married or in-union women using the methods changes over time (as the percentage of modern method use changes over time). Overall, for the 1990 reference year, survey data were from the 1983-1999 time period except for 25 countries (or 13 per cent of all countries with data) that had method mix data from 2000 or later. For the 2011 reference year, survey data were from the 20005 2012 time period except for 31 countries (or 16 per cent of all countries) that had data prior to 2000. We used several measures of the effectiveness and concentration of methods used among all contraceptive users from prior studies. The first measure is the average method effectiveness of the methods used. It is constructed by multiplying the proportion of all users according to the method they use by the complement of the proportion of users who become pregnant during the first 12 months of typical use of the specific method (pregnancy rates from typical use are defined as the percentage of couples who experience an accidental pregnancy during the first year if they do not stop use of the method for any other reason). We used pregnancy rates from typical use of a method based on the experience of women in the United States and corrected for under-reporting of abortion (Hatcher et al. 2011). The method-specific pregnancy rates used are: Female sterilization (0.5 per cent), male sterilization (0.15 per cent), pill (9 per cent), injectable (6 per cent), implant (0.05 percent), IUD (0.5 per cent (the average from two common types of IUD)), male condom (18 per cent), vaginal barrier methods (12 per cent, we used the lower failure rate of the diaphragm compared with other barrier methods), other modern methods (21 per cent, we used the lower failure rate of female condoms compared with other methods) and traditional methods (23 per cent, we used an average from rhythm and withdrawal). Alternative pregnancy rates due to method failure are also available based on Demographic and Health Survey data from 19 countries (Ali et al. 2012). The methodspecific median values of failure rates for the first 12 months of use are lower than those from the United States with the exception of the IUD (1.1 per cent versus 0.5 per cent). The failure rates become more similar once the 24-month duration of use is taken into account, except for IUD (a higher failure rate) and the injectable and condom (lower failure rates). We opted to use the higher failure rates (and thus lower method effectiveness) from the United States in our calculations of the effectiveness of the method mix since the rates were adjusted for the under-reporting of abortion. Higher values of average method mix effectiveness (with a maximum value of 0.995) signify a 6 more effective method mix profile and, by implication, fewer unintended pregnancies among women who use contraception. The second measure is an exploratory measure of the effectiveness of total demand for contraception. Total demand is the sum of contraceptive prevalence and unmet need for family planning. Similar to the average effectiveness of the method mix, we multiplied the proportion of all women with a demand for family planning according to the method they used by the complement of the proportion of users who become pregnant during the first year of typical use of the specific method. For the proportion of women with an unmet need for family planning, we used the same assumption in other research of unintended pregnancy (see Darroch and Singh 2011) that 40 per cent of women who want to avoid pregnancy but are not using a method will become pregnant over a 12-month period. The figure from the United States is much higher—an 85 per cent pregnancy rate for women who are not using any contraceptive method—though this is based on couples where contraception is not used and from women who cease using contraception in order to become pregnant. The lower pregnancy rate assumption reflects the fact that not all women are exposed to the risk of pregnancy (e.g., some are not fecund, some are not having sex regularly). We applied the complement of the proportion of women who become pregnant in the first year of not using contraception (or 1 - 0.40= 0.60). This summary measure of the effectiveness of total demand indicates the degree to which women’s preferences to prevent pregnancy are being met effectively, and takes into account not only shifts in the distribution of users by method used but also changes in the percentage of women who are not using contraception but who express a preference to delay or stop childbearing. We assess the concentration of method mix distributions with two measures. The first is a dichotomous indicator of whether 50 per cent or more of contraceptive use is accounted for by a single contraceptive method (Sullivan et al. 2006). The second measure captures the breadth of modern methods used and is computed as the difference in prevalence rates between the most prevalent modern method (of the nine method categories examined) and the third-most prevalent method, divided by total modern method prevalence 7 (USAID 2012). The higher the value, the more concentrated modern method use is among just a few methods. Results Trends in the distribution of contraceptive users by method In 2011, female sterilization and IUDs were the two most common methods used by women worldwide who were aged 15-49 and married or in a union (figure 1 panel A and appendix table 2). About 19 per cent of the world’s married women of reproductive age opted for female sterilization and 14 per cent used the IUD. Temporary methods were less common: 9 per cent of women used the pill, 8 per cent relied on male condoms and 4 per cent used injectables. Only 6 per cent of married or in-union women worldwide used traditional methods as of 2011. The distributions of contraceptive users by methods used are quite distinct across regions and countries. Short-term and reversible methods, such as the pill, injectable and condom, were more commonly used than other methods in Africa and Europe whereas longer-term and permanent methods, such as sterilization, implants and the IUD, were more common in Asia and Northern America. Latin America and the Caribbean and Oceania were more balanced in the prevalence of short-term versus long-term methods. For example, the IUD was most commonly used in Asia (18 per cent) and levels were over 25 per cent in China, Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Viet Nam and four countries in Central Asia. Female sterilization was most prevalent (more than 20 per cent) in Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean and Northern America in 2011 and levels were over 25 per cent in several populous countries (i.e., Brazil, China, India and Mexico). Use of the contraceptive pill has the widest geographic distribution of any method. Other modern contraceptive methods are also popular in certain regions. In Africa, for instance, injectables as well as the pill are the most common methods used (8 per cent each). Between 1990 and 2011, all modern contraceptive methods increased in prevalence worldwide except for vasectomy and vaginal barrier methods, the former due principally to declining prevalence of vasectomy in several Asian countries, especially the two 8 largest, China (from an estimated 8.6 per cent in 1990 to 4.5 per cent in 2011) and India (from an estimated 3.5 per cent in 1990 to 1.2 per cent in 2011). Nine out of every 10 married or in-union women using contraception in the world in 2011 relied on modern methods of contraception, and more than half of users relied on either female sterilization or the IUD (figure 1 panel B and appendix table 3). Modern methods requiring male participation are not common: only 17 per cent of married or inunion women worldwide who used contraception relied on male sterilization or male condoms. The regions with the highest proportion of use of traditional methods in 2011 were Africa (18 per cent of use) and Europe (16 per cent of use). Change over the past 20 years in the distribution of contraceptive users by methods used has occurred slowly at both the global and regional levels. Permanent or long-lasting methods have declined slightly and short-term and reversible methods have increased. Sterilization declined from 38 per cent of all use in 1990 to 34 per cent in 2011 and the IUD declined from 24 per cent to 22 percent. For the world as a whole, the pill’s share of total contraceptive use remained stable over the past 20 years (14 per cent), while the share due to injectables has risen (from 2 to 6 per cent) as they became more widely available in Africa (rising from 9 per cent of all use in 1990 to 27 per cent of all use in 2011). Since 1990, the share of total contraceptive use accounted for by traditional methods declined sharply the regions where their use had been common: in Africa (from 27 per cent to 18 per cent of all use) and Europe (from 30 per cent to 16 per cent of all use). 9 Figure 1. Prevalence of method-specific use and the distribution of contraceptive users by method used, by major area and development region, 1990 and 2011 A. Percentage of women using specific methods among those aged 15- 49 who are married or in a union 8 0 .0 Traditional 7 0 .0 O ther modern methods 6 0 .0 Vag inal barrier method Male c ondom 5 0 .0 IUD 4 0 .0 Implant Injectable 3 0 .0 P ill Male s ter . 2 0 .0 Female s ter. 1 0 .0 0 .0 rl Wo d- 1 1 1 11 11 0 01 1 0 01 1 2 01 99 0 2 01 99 02 01 99 0 2 0 02 0 19 9 2 1 99 2 -1 -1 -1 9 90 19 9 ia a-1 pe ca i s i o n a r A r n c ea Af Eu eri bea Oc ri b Am Ca rn e & h rt er No Am t in a L B. Percentage of share of overall method use 100% 90% Traditional 80% O ther modern methods 70% Vag inal barrier method 60% Male condom 50% IUD Implant 40% Injectable 30% P ill 20% Male s ter. Female s ter. 10% 0% W d o rl 1 1 1 11 11 0 01 1 01 1 2 01 99 02 01 99 0 2 01 99 0 2 0 9 90 2 0 1 99 2 9 02 -1 -1 -1 -1 9 90 9 1 e a 1 a i a i ri c As r op nca e an Af Eu eri be a Oc ri b Am a n C er r& r th me No A t in La 10 Average method mix effectiveness Given the slow change in the distribution of contraceptive users by method used at the global level, it is not surprising that the average effectiveness score of method use across 10 methods changed little from 1990 to 2011, remaining steady at 0.93-0.94 (table 1). Across major regions and subregions, the range of method mix effectiveness scores in 2011 was from 0.81 in Middle Africa to 0.97 in Eastern Asia (table 1) and across countries the range in 2011 was from 0.78 in Somalia and South Sudan to 0.97 in China (the red data points in figure 2). The largest changes over time were in Eastern Africa (from 0.87 in 1990 to 0.91 in 2011) and Western Africa (from 0.84 in 1990 to 0.87 in 2011). Across all other subregions method mix effectiveness changed little over the past twenty years and, where it declined slightly, average scores were already relatively high in 1990 (0.91 or higher). The summary measure of the average effectiveness of total demand shows much more variability over time as it incorporates changes (usually declines over time) in the proportion of total demand comprised by unmet need for family planning. In 2011, the average effectiveness of total demand for contraception was 0.88 worldwide (table 1). Across subregions, average effectiveness of total demand was below 0.80 in three subregions of Africa (Eastern, Middle and Western Africa) and in Melanesia/Micronesia/Polynesia. Among countries, the range in this score in 2011 was from 0.63 in South Sudan to 0.96 in China (figure 2), and all 19 countries with an average effectiveness score below .70 in 2011 were in sub-Saharan Africa (with relatively low contraceptive prevalence and high unmet need). 11 Figure 2. Average effectiveness of method mix and total demand among countries by contraceptive prevalence level, 2011 1 .0 0 0 .9 5 0 .9 0 Avg. e ffe c tiv e ne s s to tal de m and (2 0 1 1 ) 0 .8 5 0 .8 0 0 .7 5 Avg. e ffe c tiv e ne s s 1 0 m e tho ds (2 0 1 1 ) 0 .7 0 0 .6 5 0 .6 0 0 .5 5 0 .5 0 0 .0 1 0 .0 2 0 .0 3 0 .0 4 0 .0 5 0 .0 6 0 .0 7 0 .0 8 0 .0 9 0 .0 C o ntrace ptiv e pre v ale nc e (2 0 1 1 ) The average effectiveness of total demand increased globally and in all subregions except in Western Europe, Northern America and Oceania. Generally, the larger the increase is in contraceptive prevalence between 1990 and 2011, the larger the improvement in the average effectiveness of total demand. Thus, while the method mix effectiveness of contraceptive users may have changed little over time for subregions where most women were already using highly-effective methods, the degree to which all women were able to prevent pregnancy effectively increased over time once women who wanted to prevent pregnancy but were not using any methods were included in the picture. 12 Table 1. Change in contraceptive prevalence and measures of effectiveness and concentration of method mix distributions by development group and region, 1990 and 2011 C o n t ra ce p ti ve p r ev a len ce 1 9 90 2011 A ve ra g e e ff ec ti ve n e ss A v e ra g e ef f ec tiv e n es s o f o f 1 0 m et h o d s to t al d em an d A n y o n e m et h o d > 5 0 % o f c o n tr a cep tiv e p re va le n ce C o n c en t ra t ed m o d er n m et h o d u s e A b s o lu te ch a ng e P r o b ab ility o f c h an g e 19 9 0 2 0 11 A b s o lu te ch a n ge 1990 2 01 1 A b s o lu te ch an g e 1 9 90 2 0 11 A b s o lu te c h an g e 1 99 0 2011 A b s o lu te ch an g e W o r ld 5 5 .0 6 3 .2 8 .2 1.0 0 0 0 .9 4 0 .9 3 -0 .0 0 4 0 .8 6 0 .88 0 .01 0 0 0 0 .19 0 .1 7 -0 .0 2 A f ric a Ea s ter n A f ric a M i dd le A f ri ca N o r th er n A fr ic a S o u th er n A fr ic a W es te rn A fr ica 1 7 .8 1 2 .0 1 1 .3 3 7 .8 4 6 .6 8 .2 3 1 .3 3 3 .7 2 0 .9 5 3 .6 6 2 .6 1 5 .1 1 3 .5 2 1 .8 9 .5 1 5 .9 1 5 .8 6 .9 1.0 0 0 1.0 0 0 1.0 0 0 1.0 0 0 0.9 7 2 1.0 0 0 0 .8 9 0 .8 7 0 .8 0 0 .9 2 0 .9 4 0 .8 4 0 .9 1 0 .9 1 0 .8 1 0 .9 3 0 .9 3 0 .8 7 0 .0 1 4 0 .0 3 9 0 .0 1 4 0 .0 0 9 -0 .0 0 9 0 .0 3 6 0 .7 2 0 .6 8 0 .6 6 0 .8 0 0 .8 3 0 .6 6 0 .78 0 .78 0 .70 0 .86 0 .87 0 .70 0 .06 0 .10 0 .04 0 .06 0 .04 0 .04 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 -1 0 .35 0 .39 0 .12 0 .47 0 .24 0 .25 0 .1 5 0 .4 6 0 .2 9 0 .3 7 0 .2 7 0 .2 2 -0 .2 1 0 .08 0 .17 -0 .1 0 0 .03 -0 .0 3 A s ia C en tr al A s ia Ea s ter n A s ia S o u th er n A s ia S o u th -E as te rn A s i a W es te rn A s ia 5 6 .7 5 1 .3 7 6 .7 3 9 .0 4 8 .3 4 4 .0 6 7 .0 5 9 .4 8 2 .3 5 6 .2 6 2 .9 5 7 .9 1 0 .3 7 .9 5 .5 1 7 .1 1 4 .6 1 3 .9 1.0 0 0 0.9 0 1 0.8 8 3 0.9 9 9 1.0 0 0 1.0 0 0 0 .9 6 0 .9 4 0 .9 7 0 .9 4 0 .9 3 0 .8 6 0 .9 4 0 .9 5 0 .9 7 0 .9 3 0 .9 2 0 .8 8 -0 .0 1 3 0 .0 1 3 -0 .0 0 7 -0 .0 1 5 -0 .0 0 7 0 .0 1 8 0 .8 8 0 .8 5 0 .9 4 0 .8 2 0 .8 4 0 .7 8 0 .89 0 .89 0 .95 0 .86 0 .87 0 .82 0 .01 0 .03 0 .00 0 .04 0 .03 0 .04 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 .33 0 .84 0 .29 0 .59 0 .13 0 .25 0 .2 6 0 .7 2 0 .3 3 0 .4 9 0 .1 9 0 .1 8 -0 .0 6 -0 .1 2 0 .04 -0 .1 0 0 .06 -0 .0 7 E u ro p e Ea s ter n Eu r o pe N o r th er n E u ro p e S o u th er n E u ro p e W es te rn E u ro p e 6 8 .4 6 5 .5 7 3 .5 6 4 .7 7 4 .0 7 0 .0 7 0 .1 7 7 .6 6 5 .8 6 9 .9 1 .6 4 .5 4 .0 1 .1 -4 .0 0.7 6 3 0.8 6 1 0.9 1 4 0.5 9 6 0.1 3 1 0 .8 8 0 .8 6 0 .9 1 0 .8 4 0 .9 1 0 .8 9 0 .8 6 0 .9 1 0 .8 6 0 .9 1 0 .0 0 7 0 .0 0 6 -0 .0 0 1 0 .0 2 4 0 .0 0 0 0 .8 4 0 .8 2 0 .8 8 0 .8 0 0 .8 8 0 .85 0 .83 0 .88 0 .82 0 .88 0 .01 0 .01 0 .01 0 .02 -0 .0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .16 0 .44 0 .17 0 .23 0 .54 0 .1 5 0 .2 1 0 .1 4 0 .2 6 0 .4 5 -0 .0 1 -0 .2 3 -0 .0 3 0 .03 -0 .0 9 L a tin A m e ric a an d th e C a ri b b ea n C ar ib b ean C en tr al A m er ica S o u th A m er ica 6 1 .0 5 4 .0 5 5 .6 6 4 .0 7 2 .8 6 0 .7 6 9 .6 7 5 .6 1 1 .8 6 .7 1 3 .9 1 1 .5 1.0 0 0 0.9 9 1 0.9 9 5 0.9 9 8 0 .9 2 0 .9 5 0 .9 3 0 .9 2 0 .9 3 0 .9 4 0 .9 4 0 .9 2 0 .0 0 4 -0 .0 1 5 0 .0 1 2 0 .0 0 1 0 .8 5 0 .8 6 0 .8 4 0 .8 6 0 .89 0 .86 0 .89 0 .89 0 .03 0 .00 0 .05 0 .03 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 .26 0 .26 0 .23 0 .30 0 .2 4 0 .2 5 0 .4 2 0 .1 6 -0 .0 1 -0 .0 1 0 .19 -0 .1 4 N o rt h e rn A m e ric a 7 2 .0 7 5 .4 3 .4 0.7 9 1 0 .9 3 0 .9 2 -0 .0 1 1 0 .9 0 0 .89 -0 .0 1 0 0 0 0 .16 0 .1 3 -0 .0 4 O cea n ia A u s tr alia /N ew Z ea lan d 6 1 .9 7 1 .3 5 9 .4 6 9 .0 -2 .4 -2 .2 0.3 2 0 0.3 6 7 0 .9 2 0 .9 2 0 .9 2 0 .9 2 0 .0 0 0 0 .0 0 1 0 .8 6 0 .8 8 0 .85 0 .88 -0 .0 1 0 .00 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 .22 0 .22 0 .0 6 0 .0 4 -0 .1 6 -0 .1 8 M e lan e s ia/M ic ro n e s ia/ P o ly ne s ia 2 8 .3 3 6 .9 8 .4 0.9 0 0 0 .9 0 0 .9 1 0 .0 0 2 0 .7 5 0 .78 0 .03 0 0 0 0 .14 0 .1 7 0 .02 So ur c e s : M od e l -ba s e d e s t i m a te s ba s e d o n A l ke m a e t a l. (20 13 ) us i ng m e t ho d-m i x c om pu ta ti o ns ba s e d o n U ni t e d N a tio ns (2 01 2, 20 13 ). Among the 188 countries examined, the average method mix effectiveness score increased in 103 countries (or 55 per cent of all countries) from 1990 to 2011 and the range of change varied widely across countries, from -0.05 in Botswana to 0.13 in Burkina Faso and Djibouti. Figure 3 shows the 188 countries by absolute change between 1990 and 2011 in method mix effectiveness scores and the percentage point change in contraceptive prevalence according to a country’s average method mix effectiveness score in 1990 (with 0.90 used as a cut-point to distinguish high from low effectiveness). Increases in contraceptive prevalence were not generally associated with increased method mix effectiveness. Increases in contraceptive prevalence since 1990 were not associated with improvements in method mix effectiveness, even among countries with less effective method mix profiles in 1990 (R2 of 0.004). Figure 3. Absolute change from 1990-2011 in average method mix effectiveness and contraceptive prevalence for 188 countries, by method mix effectiveness in 1990 0 .1 4 A bso lute c ha ng e in a v era g e m etho d m ix effectiv e ness 0 .1 2 0 .1 0 Effectivenes s les s than 0 .9 0 (1 9 9 0 ) 0 .0 8 Effectivenes s 0 .9 0 or hig her (1 9 9 0 ) 0 .0 6 0 .0 4 2 R = 0 .0 0 4 Linear (Effective nes s les s than 0 .9 0 (1 9 9 0 )) 0 .0 2 0 .0 0 -1 0 .0 -0 .0 2 -0 .0 4 -0 .0 6 0 .0 1 0 .0 2 0 .0 3 0 .0 4 0 .0 5 0 .0 6 0 .0 The exploratory measure of effectiveness of total demand over time provided a broad sense of change in effectiveness in pregnancy prevention over time. However, the measure is highly correlated with change in contraceptive prevalence (R2 = 0.75 among 188 countries) and thus is best used as a summary measure that includes both coverage of family planning among women who want to delay or stop childbearing and the effectiveness of methods used. Method mix concentration The dominance of a single method among married or in-union women who use contraception occurred in only four subregions (table 1) and the specific methods that dominated varied. In 2011, one method accounted for 50 per cent or more of use in Central Asia (IUD is 72 per cent of total use), Middle Africa (traditional methods are 57 per cent of total use), Southern Asia (female sterilization is 52 per cent of total use) and Western Europe (pill is 54 per cent of use). The same methods also dominated use in these subregions in 1990 as well. Only Western Africa moved from the dominance of traditional methods in 1990 (56 per cent of total use) to no dominant method in 2011. Among the 188 countries in 2011, a single method accounted for at least half of all contraceptive use in 52 countries (or 28 per cent of all countries), 13 of which moved into a skewed method distribution over time while the remaining 39 countries had a skewed distribution in 1990 (table 2). The most common dominant methods in 2011 were the pill and traditional methods. Countries with a dominant single method spanned geographic regions and contraceptive prevalence levels. For example, Ethiopia had a 28 per cent contraceptive prevalence rate in 2011 and 73 per cent of users relied on injectables while Mexico had a 72 per cent contraceptive prevalence rate in 2011 and 53 per cent of users relied on female sterilization). An additional 30 countries moved from a disproportionate reliance on one method in 1990 to a more balanced distribution in 2011. While the unweighted average change in contraceptive prevalence was highest (12 percentage points) among countries with more balanced method distributions in both 1990 and 2011, there was no clear pattern in the magnitude of contraceptive prevalence change by whether countries had a dominant method or not. 15 Table 2. Number of countries with one dominant method of contraception and the unweighted percentage point change in contraceptive prevalence, 1990 to 2011 Number of countries Percentage of countries Percentage point change in contraceptive prevalence (unweighted) No dominant method (1990 & 2011) 106 56.4 12.2 Decrease (dominant method in 1990, none in 2011) 30 16.0 8.5 Increase (none in 1990, dominant method in 2011) 13 6.9 11.1 Dominant method (1990 & 2011) 39 20.7 8.7 Dominant methods in 2011 Pill Traditional methods Injectables IUD Female sterilization Male condoms 20 11 8 7 4 2 The second measure of concentrated modern method mix indicates the amount and distribution of modern method prevalence accounted for by the top three modern methods. It is computed as the difference in prevalence rates between the most prevalent modern method and the third-most prevalent method, divided by total modern method prevalence (USAID 2012). Higher values indicate a higher concentration of use on a limited number of methods (with a maximum value of 1, when all modern method use is attributable to one method). Declines over time (negative values of absolute change) indicate movement towards a more balanced distribution of modern methods among married or in-union women using modern methods. At the global level, the distribution of modern methods (with the top three methods being female sterilization, IUD and pill) became more balanced from 1990 to 2011 according to this measure (see table 1), declining from 0.19 in 1990 to 0.17 in 2011. Wide relative distances between the first and the third modern methods – showing an unbalanced mix of modern methods – were in Central Asia (value of 0.72, top three modern methods 16 were IUD, pill and male condom), Southern Asia (value of 0.49, top three modern methods were female sterilization, pill and male condom), Eastern Africa (value of 0.46, top three modern methods were injectables, pill and female sterilization) and Western Europe (value of 0.45, top three modern methods were pill, IUD and male condom). Married or in-union women in Africa, Northern America, Europe and Oceania had the most balanced distribution of modern method use among all regions (scores of 0.15 or lower in 2011). Interestingly, each sub-region of Africa shows modern method use concentrated on three or fewer methods, but since the types of methods that dominate vary across sub-regions (e.g., injectables dominate in Eastern Africa while the pill and IUDs dominate in Northern Africa), the distribution for the region as a whole is more balanced. Countries with very high modern method prevalence (over 70 per cent among married or in-union women) also had the most balanced distributions of modern methods: for example, Australia, Austria, Canada, Cuba, New Zealand, Paraguay, United Kingdom and United States of America each had modern method prevalence of over 60 per cent in 2011 and a score on the concentrated modern method use of 0.15 or below. However, other countries achieved a high prevalence of modern methods with a high method mix concentration. For example, at similarly high levels of modern contraceptive prevalence, Dominican Republic, Germany, Portugal and Uzbekistan had a concentrated modern method use score of 0.50 or higher. There is no evidence that increases in modern method use over the past 20 years were related to less concentrated modern method distributions (figure 4). For countries where contraceptive prevalence in 1990 was less than 60 per cent, there was a small positive correlation (R2 = 0.02) between increasing contraceptive prevalence from 1990 to 2011 and a decline in concentration of modern method mix over the same period. 17 Figure 4. Absolute change from 1990-2011 in concentrated modern method mix and modern contraceptive prevalence for 188 countries, by contraceptive prevalence rate in 1990 0 .6 0 A bso lute cha ng e in co ncentra te d m o dern m etho d m ix 0 .4 0 Modern method us e les s than 6 0 per ce nt (1 9 9 0 ) 0 .2 0 2 R = 0 .0 1 6 7 0 .0 0 -1 0 .0 Modern method us e 6 0 per cent or more (1 9 9 0 ) 0 .0 1 0 .0 2 0 .0 3 0 .0 4 0 .0 5 0 .0 6 0 .0 Linear (Moder n me thod us e les s than 6 0 per cent (1 9 9 0 )) -0 .2 0 -0 .4 0 -0 .6 0 Discussion We provided estimates of the distribution of contraceptive users by method for 188 countries at two time points, 1990 and 2011, and computed several measures of the effectiveness and concentration of contraceptive methods used to characterize global, regional and country-level changes over time. We standardized comparisons in method mix over time by drawing on annual, model-based estimates of contraceptive prevalence (total, modern and traditional) and unmet need for family planning, an improvement over prior studies of contraceptive method mix that faced the common challenges of data with uneven time periods or partial geographic coverage (Bongaarts and Johansson 2002; Seiber et al. 2007; Sullivan et al. 2006; Sutherland et al. 2011). 18 Female sterilization and the IUD were the two most common methods used by women worldwide who were aged 15-49 and married or in a union, representing more than half of all methods used in both 1990 and 2011. Geographical differences in method mix profiles were large and change over the past 20 years occurred slowly. Similarly, average use-effectiveness method mix profiles changed little from 1990 to 2011. The introduction and adoption of relatively new contraceptive technologies, such as injectables and implants, or older methods, such as sterilization and pills, are contingent on both supplyside factors (e.g., governmental regulation, public and private sector promotion and distribution of methods) and demand-side factors (e.g., preferences for stopping or spacing pregnancies, ease and acceptability of use, perceptions of health side effects or social opposition). Empirical evidence also suggests that decisions about contraceptive method use are path-dependent; that is, people are often more prone to adopt or continue to use the methods they know best (or know best from the experience of friends or family) rather than adopt or switch to a new or under-utilized method (see Potter, 1999, for an in-depth analysis of Brazil and Mexico of persistent method mix distributions and tendencies for the distribution of methods used to become concentrated over time). Despite the slow changes at the global level, several important changes took place in select regions, such as a decline in traditional method prevalence in Europe and an increase in use of injectables in Africa, and at the national level, where the prevalence of individual methods and their position among other methods have shifted dramatically in some countries. We also examined the degree to which a rise in contraceptive prevalence over time was associated with increases in the average use-effectiveness and decreases in the concentration of methods used. Despite the objectives set forth in international agreements on what ideally should happen—that is, improved access to the widest possible range of safe and effective family-planning methods—there is little empirical evidence to suggest that increases in contraceptive prevalence since 1990 have been associated with increased effectiveness of method use or a more balanced modern method mix for countries. 19 The exploratory measure of effectiveness of total demand captured the degree to which all women who want to delay or stop childbearing are able to prevent pregnancy effectively. It provided a broader sense of change in effectiveness in pregnancy prevention over time and integrated both changes in the effectiveness of methods used by married or in-union women and changes in the prevalence of unmet need for family planning. The measure showed greater variability over time and space and, since it is sensitive to changes in unmet need, perhaps merits consideration as a summary measure of coverage of family planning among women who want to delay or stop childbearing and the effectiveness of methods used. This study has several limitations. First, we focused on women’s utilization of contraceptive methods and did not take into account characteristics of the supply and delivery aspects of family planning services or the composition of women’s fertility preferences (to space or stop childbearing), both of which affect the types of methods that women use over time. Second, most of the data and all of the computed measures using model-based estimates of family planning are with reference to reproductive-aged women who are married or in a cohabiting union. Patterns of method mix profiles among sexually-active women are likely quite distinct from married or in-union women, and thus separate estimates are needed for both populations. Third, the measures of method mix concentration were somewhat problematic. The dominant method indicator (50 per cent or more of contraceptive use attributed to one method) misses more subtle differences and changes over time in the distribution of methods. The second measure of the relative distance between prevalence of the first and the third most common modern method was more difficult to interpret apart from at a value of 1, only one method is used. Furthermore, the values indicated a high concentration of modern methods in subregions of Africa, but at the higher level of Africa, the method mix profile was relatively balanced due to the fact that in each subregion different methods were dominant (table 1). We suggest exploring other measures of concentration used in other substantive research areas. 20 Recent international efforts to expand access to effective contraceptive methods have brought renewed attention to issues of method mix and quality of care in family planning services. For example, the Family Planning 2020 initiative, spearheaded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, began in 2012 with the goal of providing modern contraceptive methods to an additional 120 million women in 69 of the world’s poorest countries by 2020. Over $2.6 billion in financial commitments were made in this regard. A diverse mix of effective methods theoretically provides more choices for women and men and better matches of methods to individual needs. Thus, improving the mix of methods available to women and men could help ensure that individuals are able to prevent pregnancy in an effective manner, to switch easily to another method if they are unsatisfied with their current method, to match better their fertility preferences to a specific contraceptive method (e.g., for those who want to stop childbearing, a permanent or long-acting method may be preferable to a short-term method) and, in general, to realize their rights to determine if, when and how many children they want to have. The evidence examined in this study provides a more qualified view of the potential impact of increasing the range of methods available to, and used by, women and men on contraceptive prevalence and unmet need for family planning. 21 References Ali MM, Cleland J, Shah IH. 2012. Causes and consequences of contraceptive discontinuation: evidence from 60 demographic and health surveys. Geneva: World Health Organization. Alkema L, Kantorova V, Menozzi C, Biddlecom A. 2013. National, regional and global rates and trends in contraceptive prevalence and unmet need for family planning between 1990 and 2015: a systematic and comprehensive analysis. Lancet 2013; published online March 12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62204-1. Bongaarts J, Johansson E. 2002. Future trends in contraceptive prevalence and method mix in the developing world. Studies in Family Planning 33(1):24–36. Darroch JE, Singh S. 2011. Estimating unintended pregnancies averted from couple-years of protection (CYP). Unpublished memo. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/2011/01/24/Guttmacher-CYP-Memo.pdf Hatcher R, et al. 2011. Contraceptive Technology, Revised 20th edition. Bridging the Gap Foundation . (see Table 3-2, accessible at http://www.contraceptivetechnology.com/CTFailureTable.pdf). Potter, JE. 1999. The persistence of outmoded contraceptive regimes: The cases of Mexico and Brazil. Population and Development Review 25(4):703-739. Ross J, Hardee K, Mumford E, Eid S. 2002. Contraceptive method choice in developing countries. International Family Planning Perspectives 28(1):32-40. Seiber EE, Bertrand JT and Sullivan TM. 2007. Changes in contraceptive method mix in developing countries. International Family Planning Perspectives 33(3):117–123. Sullivan TM, Bertrand JT, Rice J, Shelton JD. 2006. Skewed contraceptive method mix: why it happens, why it matters. Journal of Biosocial Science 38(4):501-21. Sutherland EG, Otterness C, Janowitz B. 2011. What happens to contraceptive use after injectables are introduced? An analysis of 13 countries. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 37(4):202-208. United Nations. 1996. Programme of Action Adopted at the International Conference on Population and Development, Cairo. New York: United Nations. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. 2012. World Contraceptive Use 2012 (POP/DB/CP/Rev2012). Available at http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/WCU2012/MainFrame.html 22 United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. 2013. 2013 Update for the MDG Database: Contraceptive Prevalence (POP/DB/CP/A/MDG2013). Available at http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/theme/mdg/index.shtml USAID | DELIVER PROJECT, Task Order 4. 2012. A Decade of Monitoring Contraceptive Security and Measuring Successes and Opportunities around the World. Arlington, VA: USAID | DELIVER PROJECT, Task Order 4. See also http://deliver.jsi.com/dlvr_content/resources/allpubs/factsheets/CSIndexWallChart2012.p df 23 Appendix table 1. Dates of survey data used to compute method mix distributions for 1990 and 2011 Ea rlier time p erio d L at er time p erio d S am e su rv ey A FR IC A Ea st ern A f rica Bu run di Co mor os 1 98 7 1 99 6 20 10 /1 1 2 00 0 D jib ou ti Eritrea Ethio pia 2 00 2 1 99 5 1 99 0 2 00 6 2 00 2 20 10 /1 1 1 98 8/8 9 1 99 2 1 99 2 1 99 1 20 08 /0 9 20 08 /0 9 2 01 0 2 00 2 M ozam biq ue Réu nion Rw and a 1 99 7 1 99 0 1 99 2 2 01 1 1 99 7 20 10 /1 1 So uth S u dan 2 00 6 2 00 6 1 99 9 1 98 8/8 9 1 99 1/9 2 20 05 /0 6 2 01 1 2 01 0 K enya M adag as car M alaw i M aur itiu s So malia U gand a U nited R epu blic of T anzan ia Zamb ia Zimbab w e 1 99 2 2 00 7 1 98 8/8 9 20 10 /1 1 1 99 6 1 99 1 20 08 /0 9 2 01 1 s am e Mid d le A frica An go la Came roo n Cen tral A frican R ep ublic 1 99 4/9 5 2 00 6 Ch ad Co ngo D emocr atic Rep ub lic o f the C ong o 1 99 6/9 7 2 00 5 1 99 1 2 01 0 20 11 /1 2 2 01 0 Equ ator ia l G u inea 2 00 0 2 00 0 G abo n Sao To me and P r incipe 2 00 0 2 00 0 2 01 2 20 08 /0 9 1 99 2 1 99 1 1 99 5 2 00 6 2 00 8 1 99 5 1 98 7 1 98 9/9 0 1 98 8 20 10 /1 1 2 01 0 20 10 /1 1 Bo tsw an a Leso tho N amibia 1 98 8 1 99 1/9 2 1 98 9 20 07 /0 8 2 00 9 20 06 /0 7 So uth A f rica 1 98 7/8 9 20 03 /0 4 1 98 8 2 01 0 s am e N orth ern A frica Alg eria Egy pt Libya M or occo Su dan Tun isia So u th ern A frica Sw azilan d We st ern A f rica Ben in 1 99 6 20 11 /1 2 Bu rkin a Fas o 1 99 2/9 3 20 10 /1 1 Cap e V erde Cô te d 'Iv oir e 1 98 8/8 9 1 99 4 2 00 5 20 11 /1 2 G ambia G hana 1 99 0 1 99 1/9 2 2 01 0 2 00 8 G uinea 1 99 2/9 3 2 01 2 2 00 0 1 98 6 1 98 7 2 01 0 2 00 7 2 00 6 G uinea- Bis s au Liber ia M ali M aur itan ia 1 99 1/9 2 2 00 7 N ig er N ig eria Sen egal 1 99 2 1 99 0 1 99 2/9 3 2 01 2 2 01 1 20 10 /1 1 1 99 2 1 98 8 2 01 0 2 01 0 Sier ra Leo ne Tog o 24 s am e Appendix table 1. (continued) Dates of survey data used to compute method mix distributions for 1990 and 2011 A SI A C ent ral A s ia K azakh stan K yrg yzs tan 1 99 5 1 99 7 20 10 /1 1 20 05 /0 6 Tajikis tan 2 00 0 2 01 2 Tur kmen istan 2 00 0 2 00 0 U zbek istan 1 99 6 2 00 6 s am e Ea st ern A s ia Ch in a 1 98 8 2 00 6 1 99 2 1 99 0/9 2 2 00 7 2 00 2 Jap an 1 99 0 2 00 5 M on go lia 1 99 4 2 01 0 Rep ub lic o f K or ea 1 99 1 2 00 9 2 00 0 1 99 1 2 01 0 2 01 1 Ch in a, H o ng K ong SA R D em ocr atic Pe op le 's R epu blic of K o rea So u th ern A sia Af gh anis tan Ban glad esh Bh utan Ind ia 1 99 4 2 01 0 1 99 2/9 3 20 07 /0 8 1 99 2 1 99 1 2 00 2 2 00 9 Iran ( Is lamic Rep ub lic of) M aldiv es N epal Pa kis ta n 1 99 1 2 01 1 1 99 0/9 1 20 06 /0 7 1 99 3 20 06 /0 7 1 99 5 1 99 1 20 10 /1 1 2 01 2 Sr i L anka So u th -E as tern A s ia Camb od ia Ind on esia Lao P eo ple's D emoc ratic Rep ub lic 1 99 3 2 00 5 M alays ia 1 98 8 2 00 4 M yan m ar 1 99 1 20 09 /1 0 Ph ilipp ines Sin gap or e 1 99 3 1 99 2 2 01 1 1 99 7 Thailan d 1 98 9 2 00 9 Timo r-Les te 1 99 1 20 09 /1 0 V ie t N am 1 98 8 20 10 /1 1 1 99 1 2 00 0 2 01 0 2 00 6 We st ern A s ia Ar men ia Az erba ija n Bah rain 1 98 9 1 99 5 G eorg ia 1 99 9/0 0 2 01 0 Iraq Is rael 1 98 9 1 98 7/8 8 2 01 1 19 87 /8 8 1 99 0 1 98 7 2 00 9 1 99 9 Jo rd an K uw ait Leban on O man 1 99 6 2 00 4 1 98 8/8 9 2 00 0 1 98 7 1 99 6 1 99 8 2 00 7 Q atar Sau di A rab ia State o f P alestin e 1 99 6 2 00 6 Sy rian A ra b Rep ub lic 1 99 3 2 00 6 Tur key 1 98 8 2 00 8 U nited A rab Em ira te s 1 99 5 1 99 5 Y em en 1 99 2 2 00 6 25 s am e s am e Appendix table 1. (continued) Dates of survey data used to compute method mix distributions for 1990 and 2011 EU R O PE Ea st ern E u rop e Belar us 1 99 5 20 05 /0 6 Bu lgaria 1 99 5 2 00 7 Czech Rep ub lic 1 99 1 2 00 8 H ung ary 1 98 6 19 92 /9 3 Po land 1 99 1 1 99 1 Rep ub lic o f M old ov a 1 99 7 2 00 5 1 99 3 2 00 5 Ro mania Ru ss ian F ede ration s am e 1 99 2/9 3 2 00 7 Slo vak ia 1 99 1 1 99 7 U krain e 1 99 9 2 00 7 N orth ern E ur op e D enmar k Esto nia 1 98 8 1 99 4 1 98 8 20 04 /0 5 s am e Fin land 1 98 9 1 98 9 s am e Irelan d 1 99 8 20 04 /0 5 Latvia 1 99 5 1 99 5 Lithuan ia 1 99 4/9 5 2 00 6 N orw ay 1 98 8/8 9 2 00 5 Sw ed en 1 99 6 1 99 6 U nited K ing do m 1 98 9 20 08 /0 9 So u th ern Eu ro pe Alb ania 2 00 0 20 08 /0 9 Bo sn ia and H er zego vin a 2 00 0 20 11 /1 2 G reece Italy M alta 1 98 3 2 00 1 1 99 5/9 6 1 99 3 19 95 /9 6 1 99 3 M on teneg ro 2 00 0 20 05 /0 6 Po rtu gal 1 99 7 20 05 /0 6 Ser bia 2 00 0 2 01 0 Slo ven ia 1 99 4/9 5 19 94 /9 5 Sp ain 1 99 4/9 5 2 00 6 We st ern E u rop e Au s tr ia 1 99 5/9 6 20 08 /0 9 Belg ium 1 99 1/9 2 20 08 /1 0 s am e s am e s am e s am e s am e Fr ance 1 98 8 2 00 8 G erman y N etherlan ds 1 99 2 1 99 3 2 00 5 2 00 8 Sw itzer la nd 1 99 4/9 5 19 94 /9 5 s am e An gu illa 2 00 3 2 00 3 s am e An tigu a an d B arb ud a 1 98 8 1 98 8 s am e Bah amas 1 98 8 1 98 8 s am e Bar bad os 1 98 8 1 98 8 s am e Cu ba 1 98 7 20 10 /1 1 D omin ica 1 98 7 1 98 7 D omin ican Re pub lic 1 99 1 2 00 7 G renad a H aiti 1 99 0 1 98 9 1 99 0 2 01 2 LA T IN A M ER I C A A N D TH E C A R I BB EA N C arib b ean 26 s am e s am e Appendix table 1. (continued) Dates of survey data used to compute method mix distributions for 1990 and 2011 Ja m a i c a 1 98 9 20 02 /0 3 M on t se r ra t 1 98 4 1 98 4 s am e 1 99 5/ 9 6 1 98 4 2 00 2 1 98 4 s am e Sa i n t L uc i a 1 98 8 1 98 8 s am e Sa i n t V i n c e n t a n d t he G re n a di n e s 1 98 8 1 98 8 s am e T ri n id a d a n d T o ba g o 1 98 7 2 00 6 U ni t e d S t a t e s V i r g i n Is l a n ds 2 00 2 2 00 2 1 99 1 2 01 1 Pu e rt o R i c o Sa i n t K i t t s a nd N e v i s s am e C e nt r a l A m e r i c a Belize C o st a R i c a E l S a l v a do r G ua t e m a l a 1 99 2/ 9 3 2 01 0 1 98 8 2 00 8 1 98 7 2 00 2 H on d ur a s M e xi c o 1 99 1/ 9 2 1 98 7 20 05 /0 6 2 00 6 N ic a ra gu a 1 99 2/ 9 3 20 06 /0 7 Pa na m a 1 98 4/ 8 5 2 00 9 So u th A m e r i c a Ar ge n t i n a 2 00 1 20 04 /0 5 B o l i v i a (P l u r i na t i o n a l St a t e o f) Br az il 1 98 9 1 98 6 2 00 8 2 00 6 C h il e 2 00 1 2 00 6 Co lom b ia 1 99 0 20 09 /1 0 1 98 9 1 99 1/ 9 2 2 00 4 2 00 9 E c ua d o r G uy a n a Pa ra g u a y 1 99 0 2 00 8 1 99 1/ 9 2 2 01 1 Su ri na m e U rug ua y 1 99 2 1 98 6 2 00 6 2 00 4 V e n e z u e l a ( B o l i va r i a n R e p u b l i c o f) 1 99 3 1 99 8 Pe ru N O R T H E R N A M E R IC A C a n a da 1 98 4 2 00 2 U ni t e d S t a t e s o f A m e ri c a 1 99 0 20 06 /1 0 Au s tr a l i a 1 99 5 20 05 /0 6 N e w Z e a la n d 1 99 5 1 99 5 s am e C o o k I sl a n d s G ua m 1 99 9 2 00 2 1 99 9 2 00 2 s am e s am e K ir i ba t i 2 00 0 2 00 9 M a rs ha l l Is l a nd s 1 98 5 2 00 7 N a u ru 2 00 7 2 00 7 s am e Pa la u Pa pu a N e w G ui n e a 2 00 3 1 99 6 2 00 3 20 06 /0 7 s am e O C E A N IA M e l a n e si a / M i c r o n e si a / P o ly n e s ia Sa m o a 1 99 8 2 00 9 2 00 6/ 0 7 20 06 /0 7 s am e T uv a l u 2 00 7 2 00 7 s am e V a n ua tu 1 99 5 2 00 7 So l om on I sl a n ds 27 Appendix table 2. Total and method-specific contraceptive prevalence (percentage) among married or in-union women of reproductive age by development group and region, 1990 and 2011 Female sterilzation Male sterilization Pill Injectable Implant IUD Male condom Vaginal barrier methods Other modern methods Traditional methods 17.1 18.9 4.0 2.4 7.9 8.9 0.9 4.1 0.1 0.5 13.0 13.9 4.4 8.0 0.4 0.2 0.1 0.2 7.1 6.1 1.3 0.1 6.1 1.5 0.0 3.2 0.6 0.1 0.1 4.8 1.7 0.0 8.1 8.3 1.0 4.6 2.0 0.0 0.1 5.5 21.5 4.7 4.5 1.0 0.2 16.1 3.7 0.0 0.0 4.8 23.4 2.2 6.4 3.7 0.4 17.5 7.4 0.1 0.1 5.6 3.7 1.9 17.0 0.0 0.0 14.4 9.4 1.2 0.0 20.6 3.8 2.7 20.5 0.5 0.1 11.9 17.7 1.4 0.3 11.0 Latin Amer &Caribbean - 1990 2011 20.9 26.2 0.6 2.3 18.3 14.9 1.3 6.1 0.0 0.3 7.4 6.5 3.4 10.1 0.7 0.2 0.0 0.0 8.3 6.1 Northern America - 1990 2011 24.5 20.8 13.6 11.9 14.2 16.6 0.0 0.1 0.0 0.6 1.5 4.7 9.7 12.0 2.8 0.1 0.9 2.9 4.5 5.2 Oceania - 1990 2011 12.3 11.0 9.3 11.2 22.4 14.3 1.4 3.6 0.0 1.5 1.9 1.8 9.8 11.6 0.1 0.1 0.7 0.0 3.7 4.1 World - 1990 2011 Africa - 1990 2011 Asia - 1990 2011 Europe - 1990 2011 Sources: Model-based estimates based on Alkema et al. (2013) using method-mix computations based on United Nations (2012, 2013). Appendix table 3. Method-specific proportional share of total contraceptive prevalence among married or in-union women of reproductive age by development group and region, 1990 and 2011 Female sterilzation Male sterilization Pill Injectable Implant IUD Male condom Vaginal barrier methods Other modern methods Traditional methods 0.31 0.30 0.07 0.04 0.14 0.14 0.02 0.06 0.00 0.01 0.24 0.22 0.08 0.13 0.01 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.13 0.10 0.07 0.00 0.34 0.08 0.00 0.18 0.03 0.01 0.00 0.27 0.05 0.00 0.26 0.27 0.03 0.15 0.06 0.00 0.00 0.18 0.38 0.08 0.08 0.02 0.00 0.28 0.06 0.00 0.00 0.08 0.35 0.03 0.10 0.05 0.01 0.26 0.11 0.00 0.00 0.08 Europe - 1990 2011 0.05 0.03 0.25 0.00 0.00 0.21 0.14 0.02 0.00 0.30 0.05 0.04 0.29 0.01 0.00 0.17 0.25 0.02 0.00 0.16 Latin Amer &Caribbean - 1990 2011 0.34 0.36 0.01 0.03 0.30 0.20 0.02 0.08 0.00 0.00 0.12 0.09 0.06 0.14 0.01 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.14 0.08 Northern America - 1990 0.34 0.19 0.20 0.00 0.00 0.02 0.14 0.04 0.01 0.06 0.28 0.16 0.22 0.00 0.01 0.06 0.16 0.00 0.04 0.07 0.20 0.15 0.36 0.02 0.00 0.03 0.16 0.00 0.01 0.06 0.19 0.19 0.24 0.06 0.02 0.03 0.20 0.00 0.00 0.07 World - 1990 2011 Africa - 1990 2011 Asia - 1990 2011 2011 Oceania - 1990 2011 Sources: Model-based estimates based on Alkema et al. (2013) using method-mix computations based on United Nations (2012, 2013). 29