End-of-Life Decisions

advertisement

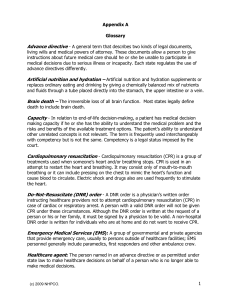

CaringInfo End-of-Life Decisions This booklet addresses issues that matter to us all, because we will all face the end of life. Advance directives — living wills and healthcare powers of attorney — are valuable tools to help us communicate our wishes about our future medical care. The questions addressed in this guide are not simple; they reflect the complexity of the choices that most of us will face in the modern medical system. Information in this booklet will help you feel comfortable that your decisions about medical care at the end of life will be honored. This booklet is divided into the following sections: Advance Care Planning ....................................................................................2 v v Living Will ....................................................................................................2 Healthcare Power of Attorney ......................................................................3 • Healthcare Agents – Appointing One ....................................................8 • Healthcare Agents – Being One ............................................................11 Life-Sustaining Treatments..............................................................................14 v v v v Artificial Nutrition and Hydration ..............................................................14 Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR)........................................................17 Do-Not Resuscitate (DNR) Orders ..............................................................18 Do-Not Intubate (DNI) Orders ....................................................................22 This booklet is intended to provide general information only and should not be construed as legal advice. Individual situations often depend upon specific circumstances. 1 End-of-Life Decisions ADVANCE CARE PLANNING Advance Care Planning What is an advance directive? “Advance directive” is a general term that describes two types of legal documents: v v Living will Healthcare power of attorney These documents allow you to instruct others about your future healthcare wishes and appoint a person to make healthcare decisions if you are not able to speak for yourself. Each state regulates the use of advance directives differently. Living Will What is a living will? A living will allows you to put in writing your wishes about medical treatments for the end of your life in the event that you cannot communicate these wishes directly. Different states name this document differently. For example, it may be called a “directive to physicians,” “healthcare declaration,” or “medical directive.” Regardless of what it is called, its purpose is to guide your family and doctors in deciding about the use of medical treatments for you at the end of life. Your legal right to accept or refuse treatment is protected by the Constitution and case law. However, your state law may define when the living will goes into effect, and may limit the treatments to which the living will applies. You should read your state’s document carefully to ensure that it reflects your wishes. You can add further instructions or write your own living will to cover situations that the state suggested document might not address. Even if your state does not have a living will law, it is wise to put your wishes about the use of life-sustaining medical treatments in writing as a guide to healthcare providers and loved ones. What is the difference between a “will,” a “living trust” and a “living will?” A will (last will and testament) and living trusts are both financial documents; they allow you to plan who receives your financial assets and property. A living will deals with medical issues while you are alive. It allows you to express your preferences about your medical care at the end of life. Wills and living trusts are complex legal instruments, for which you will need and want legal advice to complete. Although a living will is a legal document, you do not need a lawyer to complete it. 2 © 2016 National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Healthcare Power of Attorney What is a healthcare power of attorney? This can also be called a “healthcare proxy,” “appointment of a healthcare agent,” or “durable power of attorney for healthcare.” The person you appoint may be called your healthcare agent, surrogate, attorney-in-fact, or healthcare proxy. The person you appoint usually is authorized to deal with all medical situations when you cannot speak for yourself. Thus, he or she can speak for you if you become temporarily incapacitated — after an accident, for example — as well as if you become permanently incapacitated because of illness or injury. What is the difference between a financial “power of attorney,” a financial “durable power of attorney” and a “healthcare power of attorney?” A financial power of attorney and a financial durable power of attorney are both legal documents that let you appoint someone to make financial decisions for you. A power of attorney is effective only while you still handle your own finances, where as a durable power of attorney remains valid even after you have lost the ability to make financial decisions due to illness and injury. A healthcare power of attorney (which in some states is called a “durable power of attorney for medical or healthcare”) only permits the appointed person to make medical decisions for you if you cannot make those decisions yourself. It does not authorize the person to handle your financial affairs, and normally does not empower him or her to make decisions while you can still make them. Generally, the law requires your agent to make the same medical decisions that you would have made, if possible. To help your agent do this, it is essential that you discuss your values about the quality of life that is important to you and the kinds of decisions you would make in various situations. These discussions along with a living will will help your agent to form a picture of your views regarding the use of medical treatments. Why bother with an advance directive if I want my family to make the necessary decisions for me? Depending on your state’s laws, your family might not be allowed to make decisions about lifesustaining treatment for you without a living will stating your wishes. Some states laws do permit family members to make all medical decisions for their incapacitated loves ones. However, other states require clear evidence of the person’s own wishes or a legally designated decision maker. 3 End-of-Life Decisions ADVANCE CARE PLANNING Even in states that do permit family decision-making, you should still prepare advance directives for three reasons: v You can name the person with whom you are most comfortable (this person does not need to be a family member) to make sure your wishes are honored. v Your living will makes your specific wishes known. v It is a gift to loved ones faced with making decisions about your care. Should I prepare a living will and also use a medical power of attorney to appoint an agent? Yes, each document offers something the other does not. Together they provide the best assurance that your wishes will be honored. Benefits of appointing a healthcare agent: As your care needs and condition change the person who you appoint as your agent can respond in a way that no document can. In addition, you are legally authorizing that person to make decisions based not only on what you expressed in writing or verbally, but also on the knowledge of you as a person. Benefits of having a living will: If your agent must decide whether or not to begin, continue or discontinue medical treatment, your living will can reassure your agent that he or she is following your wishes. Further, if the person you appointed as an agent is unavailable or unwilling to speak for you, or if other people challenge a decision about medical treatments, your living will can guide your caregivers. What if I do not have anyone to appoint as my agent? If you do not have anyone to appoint as your agent, it is especially important that you complete a clear living will and that you talk about it with anyone who might be involved with your healthcare. This might include family members, even if you do not want them to be your agent. It also could include social workers, spiritual caregivers, visiting nurses, or aids who are helping you in some way. You should discuss it with any physicians that you see regularly and give them a copy to put in your medical record. If you are admitted to a hospital or long-term care facility, you should have a copy of your living will made a part of your medical record. 4 © 2016 National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization When will my advance directive go into effect? Your advance directive becomes legally valid as soon as you sign it in front of the required witnesses. However, it normally does not go into effect unless you are unable to make your own decisions. Each state establishes its own guidelines for when an advance directive becomes active. The rules may differ for living wills and healthcare power of attorney, as described below. Living will: In most states, before your living will can guide medical decision making, two physicians must certify that you are unable to make medical decisions and that you are in the medical conditions specified in the state’s living will law (such as “terminal illness” or “permanent unconsciousness”). Other requirements may also apply, depending upon the state. Healthcare power of attorney: Most healthcare powers of attorney go into effect when your physician concludes that you are unable to make your own decisions. If you regain the ability to make decisions, your agent cannot continue to act for you. Many states have additional requirements that apply only to decisions about life-sustaining medical treatments. Will my advance directive be honored if I am in an accident or experience a medical crisis at home and emergency technicians are called? In these emergency situations, unless you are able to speak for yourself, emergency personnel are obligated to do what is necessary to stabilize you for transfer to a hospital, both from accident sites and from a home or other facility. After a physician fully evaluates your condition and determines the underlying conditions, an advance directive can be implemented. Emergency medical technicians cannot honor a living will or healthcare power of attorney. However, in many localities, the specific crisis of cardiac arrest/respiratory arrest is addressed by a document called a “non-hospital Do-Not-Resuscitate Order.” These non-hospital DNR orders instruct emergency personnel not to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). These are physician orders that apply to situations in which the person’s heart has stopped beating or breathing has stopped. For all other conditions, emergency medical technicians are still required to treat and transport the person to the nearest hospital for evaluation by a physician. If you wish to find out whether non-hospital DNR orders are available in your locality, contact your local emergency medical services or department of health. For more information about CPR, DNR orders and non-hospital DNR orders, go to page 17 of this booklet. 5 End-of-Life Decisions ADVANCE CARE PLANNING Will my advance directive be honored in another state? The answer to this question varies from state to state. Some states do honor an advance directive from another state; others will honor out-of-state documents to the extent they match the state’s own law; and some states do not address the issue. If you spend a significant amount of time in more than one state, it is recommended that you complete an advance directive for all the states involved. It will be easier to have your advance directive honored if it is one with which the medical facility is familiar. How can I change what is in my advance directive? If you want to change anything in an advance directive once you have completed it, you should complete a new document. For this reason you should review your advance directive periodically to ensure that the forms still reflect you wishes. Must my advance directive be witnessed? Yes, every state has some type of witnessing requirement. Most require two adult witnesses; some also require a notary. Some states give you the option of having two witnesses or a notary alone as a witness. The purpose of witnessing is to confirm that you really are the person who signed the document, you were not forced to sign it, and you appeared to understand what you were doing. The witnesses do not need to know the content of the document. Generally, a person you appoint as your agent or alternative agent cannot be a witness. In some states your witnesses cannot be any relatives by blood or marriage, or anyone who would benefit from your estate. Some states prohibit your doctor and employees of a healthcare institution in which you are a resident from acting as a witness. To ensure it is completed correctly read the instructions carefully to see who can and cannot be a witness on your state-specific form. What should I do with my completed advance directive? Make several photocopies of the completed documents. Keep the original documents in a safe but easily accessible place, and tell others where you put them; you can note on the photocopies the locations where the originals are kept. DO NOT KEEP YOUR ADVANCE DIRECTIVE IN A SAFE DEPOSIT BOX. Other people may need access to them. Give photocopies to your agent and alternate agent. Be sure your doctors have copies of your advance directives and give copies to everyone who might be involved with your healthcare, such as your family, clergy, or friends. Your local hospital might also be willing to file your 6 © 2016 National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization advance directive in case you are admitted in the future. If you have surgery or are being admitted to a hospital, bring a copy with you and ask for it to be placed in your medical record. Do healthcare providers run any legal risk by honoring my advance directive? No. Most advance directive statutes explicitly state that providers run no legal risk for honoring valid advance directives. What if my healthcare provider will not honor my advance directive? In many states, healthcare providers can refuse to honor an advance directive for ethical, moral or religious reasons. For this reason, it is important to ask in advance if a healthcare provider has personal views or if an institution has any policy that would prevent them from honoring a person’s treatment choices. If you know that your personal doctor is unable or unwilling to carry out your wishes, it would be wise to change to a physician who will respect them. Who would make decisions about my medical care if I did not complete an advance directive? There is not a simple answer to this question. In general, physicians consult with families when the person cannot make decisions. A number of states have passed surrogate decisionmaking statutes. These laws create a decision-making process by identifying the individuals who may make decisions for a person who has no advance directive. Is there a federal law about advance directives? Yes, the Patient Self-Determination Act (PSDA) is a federal law regarding advance directives. It requires medical facilities that receive Medicaid and Medicare funds to have procedures for handling a person‘s advance directive, and to tell individuals upon admission about their rights under state law to use advance directives. The PSDA does not set standards for what an advance directive must say; it does not require facilities to provide advance directive forms; and it does not require people to have an advance directive. Rather PSDA’s purpose is to make people aware of their rights. Can I state my wishes about organ donation, cremation or burial in my advance directive? Several states permit you to indicate your wishes regarding organ donation. In those states that do not specifically address the issue of organ donation you may state your wishes in your advance directive. However, you should consider expressing your wishes through a form designed for that purpose. You should also make your family aware of your wishes. Since your advance directive and the authority of your agent technically ceases upon your death, you should tell your wishes about cremation or burial to your family or the executor of your estate. 7 End-of-Life Decisions ADVANCE CARE PLANNING Healthcare Power of Attorney - Healthcare Agents Healthcare Agent – Appointing One Whom can I appoint to be my healthcare agent? Your agent can be almost any adult whom you trust to make healthcare decisions for you. However, most states do not permit you to appoint your attending physician (unless the individual resigns as your physician) or employees of the facility in which you are a resident (unless they are related to you by blood or marriage). The most important considerations are that the agent be someone: v you trust v who knows you well v who will honor your wishes Ideally, it should be someone who is not afraid to ask questions of doctors in order to get information needed to make decisions. Your agent may need to be forceful and not everyone is comfortable accepting this sort of responsibility, which is why it is very important to have a discussion with the person you plan to name as your healthcare agent before you select him or her. Often people assume that their closest relatives know what they would want, so they think it is unnecessary to discuss wishes with them. However, people sometimes find that when they actually talk with their loved ones about end-of-life issues, they have very different views. Talking openly about your preferences is key to assuring that your agent knows what you want. Everyone’s situation is unique. Your decision about whom to appoint must be guided by your own relationships. 8 © 2016 National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Can I appoint more than one person to be my healthcare agent? In many states only one person can act as your agent at one time. Doctors can communicate more effectively if they know that there is one person who can receive information and make decisions. You can and should appoint an alternative agent in case the primary agent is unavailable or unable to serve. What should I tell my agent? Your agent needs to: v Know when and how you would want life-sustaining treatments provided to you v Understand personal and spiritual values that guide your thinking about death and dying v Have a copy of your living will To achieve a clearer understanding between you and your agent you might discuss some concrete situations. The following are some examples: 1. If you should suffer a massive stroke or had a head injury from which you were unlikely to regain consciousness, how you want to be treated? 2. Would you want life-sustaining treatments that might prolong your life if you suffered from a progressive debilitating disease such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s or a similar disease and could no longer make decisions? If you want treatments, which ones? For how long? Indefinitely? 3. If you were in any of these situations, would you want to receive artificial nutrition and fluids? (See page 14 for discussion on artificial nutrition and hydration) 4. If you were seriously ill and your heart stopped beating or you stopped breathing, would you want resuscitation attempts? Would you want to have a ventilator breathe for you? If so for how long? (See page 16 for discussion on cardiopulmonary resuscitation) Although you cannot review every specific situation that might arise, discussions like this can help your agent understand how you feel about the use of medical treatments at the end of life. 9 End-of-Life Decisions ADVANCE CARE PLANNING Sometimes sharing your personal concerns and values, your spiritual beliefs, or your views about what makes life worth living can be as helpful to your agent as talking about specific treatments and circumstances. For example: v How important is it to be physically independent and to stay in your own home? v How do your religious or spiritual beliefs affect your attitudes toward dying and death? And medical care? v What aspects of your life give it the most meaning? v What are your particular concerns about dying? About death? v Would you want your agent to take into account the effect of your illness on any other people? v Should financial concerns enter into decisions about your treatment? These are not simple questions and your views may change over time. It is important that you review these issues with your agent from time to time. How does my agent make decisions? Under most states’ laws your agent is expected to make decisions based on specific knowledge of your wishes. If your agent does not know what you would want in a particular situation, he or she should try to infer your wishes based on their knowledge of you as a person and on your values related to quality of life in general. If your agent lacks this knowledge, decisions must be in your best interest. Generally, the more confident the agent is about the decisions that will accurately reflect you wishes; the easier it will be to make them. In a few states, the law limits the agent’s power to refuse some treatments in certain circumstances. State law, for example, may limit decisions to what the person has specifically stated in the living will. You should carefully review your state’s documents. 10 © 2016 National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization What if I know members of my family will disagree with my wishes? To ensure that your wishes are followed, be certain that the person you appoint to be your agent understands your wishes and will abide by them. Your agent has the legal right to make decisions for you even if close family members disagree. However, should close family members express strong disagreement, your agent and your healthcare professional my find it extremely difficult to carry out the decisions you would want. If you foresee that your agent may encounter serious resistance, the following steps can help: v Communicate with family members you anticipate may object to your decisions. Tell them in writing whom you have appointed to be your healthcare agent and explain why you have done so, and send a copy to your agent. v Let them know that you do not wish for them to be involved with decisions about your medical care and give a copy of these communications to your agent as well. v Give your primary care physician, if you have one, copies of written communications you have made. v Prepare a specific, written living will. v Make it clear in your documents that you want your agent to resolve any uncertainties that could arise with interpreting the living will. A way to say this is: “My agent should make any decisions about how to interpret or when to apply my living will.” Healthcare Agent – Being One Why would I want to be a healthcare agent? Accepting the appointment to be a healthcare agent is a way of affirming the importance of your relationship to the person appointing you. However, accepting an appointment requires thoughtful consideration about whether you can fulfill the role appropriately. Acting as a healthcare agent brings significant responsibilities. What are my responsibilities as a healthcare agent? As the healthcare agent you have the power to make medical decisions if the person loses the capacity to make them. Unless your authority to act is limited by the person or the state law, you normally can make all medical decisions for the person, not only end-of-life decisions. Generally, you may speak for the person only as long as they are unable to make decisions. You need to read the state forms and the instructions carefully to find out if there are any limitations to your decision making. 11 End-of-Life Decisions ADVANCE CARE PLANNING One of an agent’s most important functions is as an advocate for the person. Advocacy can involve asking to see medical records, meeting with the physician to get information about the person’s diagnosis (the person’s illness) and prognosis (what is the likely outcome of the illness, with treatment and without treatment), and getting other information that is needed to make decisions about treatment. As the agent you may need to be assertive and persistent in seeking information and in speaking up on your loved one’s behalf. It is important for you to remember that you have the legal authority to speak for your loved one, not the physician, nurses or other healthcare professionals. How do I make decisions as a healthcare agent? Generally, you will be required, as far as possible, to make the same medical decisions that the individual you are speaking for would have made. To do this you might need to examine any specific statements that the person made (either orally or in writing, such as in a living will), as well as consider the person’s beliefs and values. If you have no information about what they would want, you must act in what you believe would be in the person’s best interest, using your own judgment. To arrive at that decision, you might ask the person’s doctors what kind of benefits and burdens might result from the treatment; and you can draw on knowledge that others have about the person and on their opinions. However, the more you and the person have talked the less likely you will be in the dark about what they would want. What do I need to know to make decisions? You can ask the physician to describe how the illness is likely to progress and what decisions are likely to be necessary at some point. If you need information from the doctors, ask for an appointment to meet and come prepared with specific questions. Write your questions down so that you do not forget any of them and you can make good use of the time. You can get information and other support from nurses, social workers, patient representatives, members of the ethics committee, and chaplains. Medical decision-making is a process. You can make provisional decisions and change them later. For example, you can authorize a trial treatment, and later if the treatment is not having the intended benefit, direct that it be stopped. Take the time you need to get the information that you feel is necessary to make a thoughtful decision. There may be no “right” decision. You can only make the best decision that you can under the circumstances. 12 © 2016 National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization If I withdraw as the agent, can anyone else make decisions for the person? If the person has appointed an alternative agent, you can withdraw and the alternate agent will become the legal decision maker. If there is not appointed alternate agent, the outcome varies among the states. In some states, law sets forth a procedure for making decisions for persons who do not have designated decision makers. However, in some states there is no provision for decision making in the absence of an appointed agent unless the person’s own wishes are clearly known. If the person’s wishes are not known, care decisions are likely left to the physician and healthcare team. How should I handle my personal feelings with acting as a healthcare agent? It is very important that you stay in touch with your own feelings while you are acting as an agent. Otherwise, you may not realize that they can affect your behavior and even your decisions. You may fear that you will not do the right thing or that you are not being assertive enough. You may worry that you are making decisions that make you feel better rather than those that are best for the person you are advocating for. You may also be struggling with grief, particularly if the illness has taken away the person you knew or if you anticipate that the person will soon die. It is hard to listen and to hear what healthcare professionals are saying when you are under emotional stress. It is difficult to be objective when you are afraid of losing someone you love. End-of-life decisions can be particularly difficult even when you know the person’s wishes very clearly. Try to accept your feelings and be patient with yourself. You can usually defer making a decision until you have a chance to think about it. Do not blame yourself if you forget to ask something or if you are afraid you made the wrong decision. If, after thinking things over, you want to change your mind, you generally can do so. As a rule, you can find another opportunity to ask questions. It is perfectly appropriate to seek help. People without medical experience cannot be expected to understand the healthcare system and the medical issues that are involved. You should expect to need guidance in dealing with them. Some physicians can be quite sympathetic to the issues you are dealing with and, if asked, will try to help. If you feel particularly comfortable with a nurse, talk with him or her. Chaplains often have a great deal of experience dealing with individuals and families struggling with difficult decisions and can be very helpful, even if you do not share a common religious outlook. Patient representatives and social workers also may be resources. Look to your own friends and communities. Sometimes people you do not know well, but who have gone through similar situations, can be a wealth of support and information. 13 LIFE-SUSTAINING TREATMENTS End-of-Life Decisions Life-Sustaining Treatments Life-sustaining treatments are medical procedures that replace or support a failing essential bodily function (one that is necessary to keep you alive). They are also sometimes called lifesupport or life prolonging treatments. Why would I not want life-sustaining treatments? If a good chance exists that a life-sustaining treatment will improve your condition (e.g., temporary use of a ventilator to support breathing until you are able to breathe on your own), you might accept the treatment. However, if your condition is complicated by many problems (e.g., serious brain damage, kidney failure) and continues to deteriorate with no likelihood of recovery, you might not want life-sustaining treatment. If I refuse life support, will I still receive treatment for any pain I might have? Yes. Many people mistakenly think that by refusing life-sustaining medical treatments they could be refusing all medical care. An individual is not refusing pain management and supportive care when they are refusing life support. This kind of care is often called “palliative care.” It is not just pain medication, although pain management is an important part of palliative care. Palliative care is care for the whole person and includes spiritual and social supports as well as support for those caring for the person. Artificial Nutrition and Hydration What is artificial nutrition and hydration? Artificial nutrition and hydration is a medical treatment that allows a person to receive nutrition (food) and hydration (fluids) when they are no longer able to take them by mouth. It is a chemically balanced mix of nutrients and fluids, provided by placing a tube directly into the stomach, the intestine, or a vein. When is it used? Artificial nutrition and hydration is given to a person who for some reason cannot eat or drink enough to sustain life or health. Doctors can provide nutrition and hydration through intravenous (IV) administration or by putting a tube in the stomach. 14 © 2016 National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Is artificial nutrition and hydration different from ordinary eating and drinking? Yes, an obvious difference is that providing artificial nutrition and hydration requires technical skill. Professional skill and training are necessary to insert the tube and to make decisions about how much and what type of food to give the person. Can I refuse artificial nutrition and hydration? Yes. Artificial nutrition and hydration are life-sustaining treatments and your refusal is protected under the law. Is it appropriate to give artificial nutrition and hydration to people who are at the end of life? Yes. As with any medical treatment, artificial nutrition and hydration should be given if they contribute to the overall treatment goals for the person. These treatment goals should always focus on the person’s wishes and interests. What does the law say about artificial nutrition and hydration? Every state law allows individuals to refuse artificial nutrition and hydration through the use of an advance directive such as a living will or durable power of attorney for healthcare. However, state laws vary as to what must be done to make wishes known. In many states nutrition and hydration is considered a medical treatment that may be refused in an advance directive. But in some states individuals are required to state specifically whether or not they would want artificial nutrition and hydration at the end of life. When there is uncertainty or conflict about whether or not a person would want the treatment, treatment usually will be continued. Can artificial nutrition and hydration be stopped once it has been started? Yes. As with any other medical treatment, stopping treatment is both legally and ethically appropriate if treatment is of no benefit to the person or it is unwanted. In fact, the law requires that treatment be stopped if the person does not want it. Conflicts about stopping artificial nutrition and hydration often arise because the person’s wishes are not clearly known or the person has not designated an agent to make decisions for him or her. In situations of uncertainty, the usual fallback option is to continue treatment. It is important that individuals talk to their doctors and loved ones about their wishes regarding the use of artificial nutrition and hydration at the end of life so they will be honored. 15 LIFE-SUSTAINING TREATMENTS End-of-Life Decisions Can anything be done if the doctor insists on providing artificial nutrition and hydration? Yes. If individuals have made their wishes known, the doctor must honor those wishes or transfer their care to another doctor who will honor them. To keep this kind of conflict from developing, it is wise for people to talk with their physicians before a medical crisis arises, if possible, so they know their physician will honor their end-of-life choices. Is it considered suicide to refuse artificial nutrition and hydration? No. When a person is refusing life-sustaining treatment at the end of life, including artificial nutrition and hydration, it is not considered an act of suicide. A person at the end of life is dying, not by choice, but because of a particular condition or disease. Continuing treatment may delay the moment of death but cannot change the underlying condition. Are life insurance policies affected if life-sustaining treatments are refused? No. Because death is not the result of suicide, life insurance policies are not affected when medical treatments are stopped. Some Points to Think About When Making Decisions About the Use of Artificial Nutrition and Hydration 1. What are your wishes? 2. What quality of life is important to you? 3. What is the goal or purpose for providing artificial nutrition and hydration? 4. Will it prolong life? Will it bring about a cure? 5. Will it contribute to the level of comfort? 6. Are there religious, cultural, or personal values that would affect a decision to continue or stop treatment? 7. Are there any benefits that artificial nutrition and hydration would offer? 16 © 2016 National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Whether to resuscitate someone who has a cardiac or respiratory arrest is one of the most common end-of-life medical decisions that individuals and their families must make. Yet many people lack the necessary information to make an informed decision about cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). What is cardiopulmonary resuscitation? Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) refers to a group of procedures that may include artificial respiration and intubation to support or restore breathing, and chest compressions or the use of electrical stimulation or medication to support or restore heart function. Intubation refers to “endotracheal incubation” which is the insertion of a tube through the mouth or nose into the tracheal (windpipe) to create and maintain an open airway to assist breathing. These procedures can either replace the normal work of the heart and lungs or stimulate the person’s own heart and lungs to begin working again. When is CPR used? CPR is used when a person stops breathing (respiratory arrest) and the heart stops beating (cardiac arrest). During cardiac arrest all body functions stop, including breathing and the blood stops going to the brain. Sometimes, however, a person may stop breathing while the heart continues to beat. This “respiratory arrest” may result from choking, or serious lung or neurological disease. If untreated, respiratory arrest will rapidly lead to cardiac arrest. Why would someone want to refuse CPR? CPR’s success rate depends heavily upon how quickly it is started and the person’s underlying medical condition. When a person is seriously ill or dying, cardiac arrest marks the moment of a disease when the body is shutting down. If CPR is initiated, it disrupts the body’s natural dying process. 17 LIFE-SUSTAINING TREATMENTS End-of-Life Decisions Do-Not-Resuscitate (DNR) Orders What is a Do-Not-Resuscitate (DNR) Order? A DNR order is a physician’s written order instructing healthcare providers not to attempt CPR in case of cardiac or respiratory arrest. A person with a valid DNR order will not be given CPR. Unlike a living will or a medical power of attorney, a person cannot prepare a DNR order. Although it is a written request of an individual, his or her family or healthcare agent, it must be signed by a physician to be valid. Why is a DNR order needed to refuse CPR? Without a physician’s order not to resuscitate, the healthcare team must initiate CPR because in an emergency there is no time to call the attending physician, determine the person’s wishes or consult the family or healthcare agent. If a person wishes to refuse CPR, that wish must be communicated to the healthcare team by a DNR order signed by the attending physician. Does a DNR order mean a person won’t receive any treatment? No. “Do not resuscitate” does not mean, “do not treat.” A DNR order covers only one type of medical treatment—CPR. Other types of treatment, including intravenous fluids, artificial nutrition and hydration, and antibiotics must be discussed with the physician separately. In addition, although CPR will not be given to a person who has a DNR order, all measures can and should be used to keep a person comfortable. Who can consent to a DNR order? An individual, his or her healthcare agent, or a family member (as provided by state law), can agree to a DNR order. Although policies may differ, in general a DNR order must first be discussed with a person if he or she has the capacity to make medical decisions. If the person is incapacitated and is unable to make this decision, a physician can then review instructions in a living will or speak with an appointed healthcare agent. If there are no written advance directives, a physician might consult a family member or a close friend of the individual. When should a DNR order be discussed with a physician? If a person is seriously ill or dying, discuss a DNR order with the physician as soon as possible. Ideally, a decision about a DNR order should be made while a person is alert and able to think clearly. However, if a person does not have the capacity to make a decision about a DNR order, it is important that this discussion be initiated as soon as possible. Ideally the physician would raise the issue, but the family or healthcare agent should not hesitate to approach the physician with their concerns. A discussion initiated sooner rather than later gives individuals and their families time to reflect on the decision. 18 © 2016 National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization What questions should be asked when discussing a DNR order with a physician? Before making a decision about CPR, individuals and their loved ones need to understand both the burdens and benefits of CPR. These can vary depending on an individual’s underlying condition. The physician should be prepared to: v Describe the procedures; v Address the probability for successful resuscitation based upon the person’s medical condition; v Define what is meant by “successful” resuscitation; Does “successful” mean the person will be able to leave the hospital? In what condition? If it is unlikely that the person will be able to leave the hospital, what can the resuscitation attempt accomplish? If the physician does not think resuscitation would be successful, he or she should be willing to discuss the reasons why. What if an individual, healthcare agent or family member disagrees with the physician’s recommendation? First, the person or appropriate family member should approach the physician to clear up any misunderstandings about the person’s wishes, prognosis, and treatment options. They can also request that a meeting be arranged with the physician, nurse and other members of the healthcare team to discuss possible reasons why an agreement cannot be reached. Often, conflicts arise because of a lack of communication. However, if differences cannot be resolved, it is important that the person, agent or family learn what resources the facility has to mediate and resolve conflict. Healthcare facilities are required to have a process in place for resolving conflicts over decisions about CPR. A social worker or patient representative may be a good source of information about what to do. The family should also ask to see a copy of the facility’s policy on DNR orders. The policy should describe the facility’s process for resolving conflict. For example, many facilities give individuals and their families the opportunity to bring disputes before an ethics committee that can provide a neutral environment in which to mediate and resolve conflict. Can a physician write a DNR order without consulting the individual? Yes, in limited circumstances. In some cases, if a person is incapacitated and an authorized decision maker is not available, a physician may, depending upon the facility’s policy, write a DNR order if he or she believes that CPR would not be a successful and appropriate treatment given the person’s underlying illness. In general, however, physicians are obligated to discuss 19 LIFE-SUSTAINING TREATMENTS End-of-Life Decisions a DNR order with an individual or his or her authorized decision maker, and must obtain consent before treatment can be withheld or withdrawn. Informed consent is a basic right that must be respected by a facility’s policy on DNR orders. Will a DNR order remain effective when a person is transferred between healthcare facilities, for example, from a nursing home to a hospital? Yes. A person’s DNR order should accompany him or her on every transfer. Once the person arrives at the new facility, a new DNR order may need to be written based on that facility’s policy. It is important that family and friends monitor the transfer to ensure that the DNR order accompanies the person and is properly documented in the medical record at the new facility. A DNR order or other important documents like a living will and medical power of attorney can be misplaced or overlooked during a transfer. Will a DNR order be honored during surgery? Usually not. DNR orders often are suspended during surgery. Cardiac or respiratory arrest during surgery may be due to the circumstances of surgery and not the underlying illness, and the chances of a successful resuscitation may be better. It is important that the individual or decision-maker talk to the surgeon in advance to make sure all parties understand what should happen in the event of an arrest during or shortly after surgery. The surgeon should also discuss how soon after surgery a DNR order will be reinstated. Can a DNR order be revoked? Yes. The individual or authorized surrogate can cancel a DNR order at any time by notifying the attending physician, who must then remove the order from the medical record. What is a non-hospital DNR order? Unlike medical facility DNR orders, non-hospital DNR orders are written for people who want to refuse CPR and are outside a healthcare facility, either at home or in a residential care setting. Also referred to as a pre-hospital DNR order, a non-hospital DNR order directs emergency medical care providers, including emergency medical technicians, paramedics and emergency department physicians, to withhold CPR. These orders must be signed by a physician and generally are written on an official form but, depending upon the state, they also may be issued on a bracelet, necklace or wallet card. Although honored by emergency medical providers, non-hospital DNR orders are not binding upon bystanders who may initiate resuscitative measures in an emergency. 20 © 2016 National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Why are non-hospital DNR orders needed? Emergencies demand an immediate response. Emergency medical service (EMS) personnel are trained to act quickly and to save lives. Once called to a scene, they must do all they can to stabilize and transport a person to the nearest hospital, including administering CPR if necessary. If a person wishes to refuse CPR in the home, he or she must have a non-hospital DNR order. Without a non-hospital DNR order, EMS will initiate CPR if a person is in cardiac or respiratory arrest. It is important to remember, however, that as long as a person has decision-making capacity, he or she can refuse any form of medical treatment, including emergency care. Are non-hospital DNR orders governed by state law? Yes. Many states have laws in place governing non-hospital DNR orders. With the growth of hospice care and the increasing desire of dying persons to spend their last days at home, has come the need to protect people from unwanted emergency care. Non-hospital DNR laws allow qualified persons to refuse emergency resuscitative measures under certain conditions. Check with the State Department of Health and county EMS agency to determine if a statewide policy or any local protocols governing non-hospital DNR orders exist. Who should consider a non-hospital DNR order and when? Non-hospital DNR orders generally are intended for seriously ill persons who have chosen to die at home. Depending upon state law or policy, there may be restrictions on who can qualify for a non-hospital DNR order. Remember, these orders must be signed by a physician to be valid. Can a non-hospital DNR order be revoked? Yes. The person or the person’s authorized surrogate can cancel a non-hospital DNR order at anytime by notifying the physician who signed the order and by destroying the form and/or bracelet, wallet card, etc. What happens to a non-hospital DNR order when someone is taken to a hospital? If a person is admitted to the hospital for any reason, it is important that the non-hospital DNR order goes with the person. If EMS personnel are involved, they should take the order with them in the ambulance, but it is still advisable for family members to bring a copy of the order with them. Although the admitting physician should write a new DNR order at the hospital, it is important that family members make sure that a facility DNR order is in place. Hospital personnel are sometimes unfamiliar with DNR laws or policies, and in an emergency, important papers can be overlooked. 21 LIFE-SUSTAINING TREATMENTS End-of-Life Decisions Do-Not-Intubate (DNI) Orders What is a Do-Not-Intubate (DNI) Order? When a DNR order is discussed the doctor might ask if a “do-not-intubate” order is also wanted. Intubation may be considered separately from resuscitation because a person can have trouble breathing or might not be getting enough oxygen before the heart actually stops beating or breathing stops (a cardiac or respiratory arrest). If this condition continues a full arrest will occur. If the person is intubated, cardiac or respiratory arrest might be averted. During intubation a tube is inserted through the mouth or nose into the trachea (windpipe) in order to assist breathing; a machine (ventilator) may be connected to that tube to push oxygen into the lungs. Refusal of resuscitation is not necessarily the same as refusal of intubation. It is important that all concerned understand the decisions being made since some institutional DNR policies include intubation, while others treat it separately. If a person does not want life mechanically sustained it is important to be sure that intubation is addressed as part of the discussion of DNR. 22 © 2016 National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization CaringInfo provides free advance directives and instructions for each state. These forms can be downloaded at www.caringinfo.org To have a free copy of your state’s advance directive forms mailed to you, contact CaringInfo: CaringInfo InfoLine 800.658.8898 Multilingual Line 877.658.8896 caringinfo@nhpco.org 23 End-of-Life Decisions ADVANCE DIRECTIVE NOTES 24 © 2016 National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization CaringInfo 800.658.8898 u 877.658.8896 (Multilingual) www.caringinfo.org u caringinfo@nhpco.org © 2016 National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization