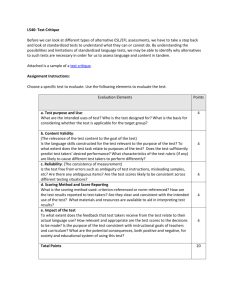

Manual for Language test development and examining for use with

advertisement