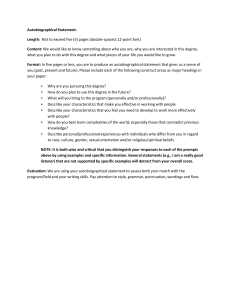

The Emergence of the Independent Self - Research portal

advertisement