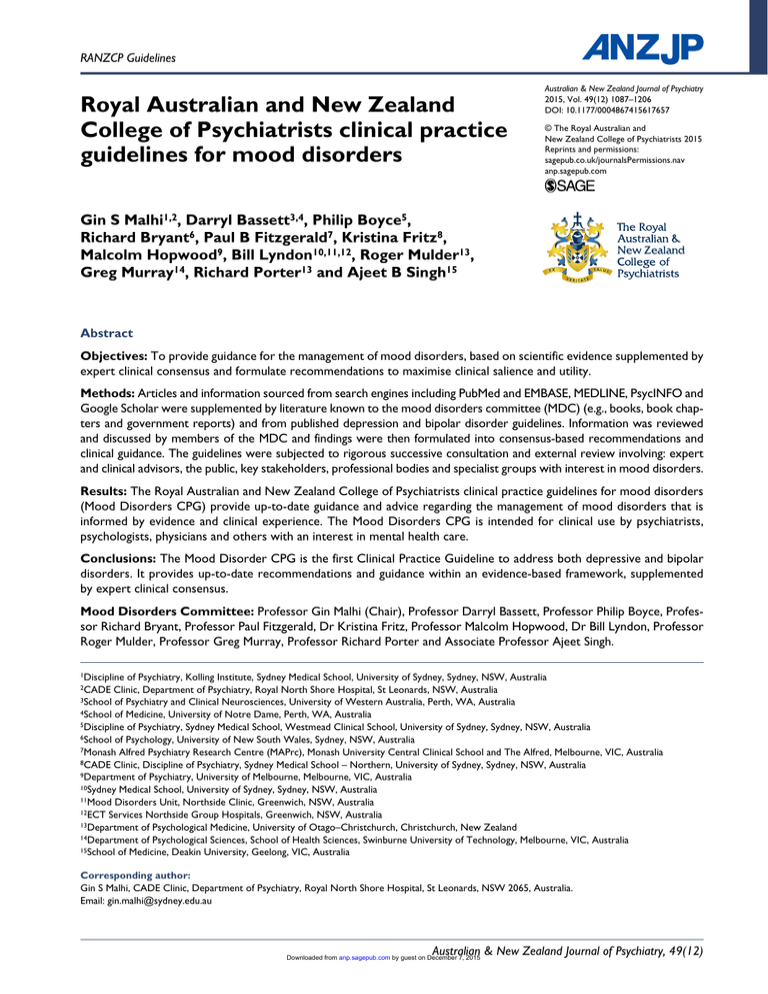

Mood disorders - Royal Australian and New Zealand College of

advertisement