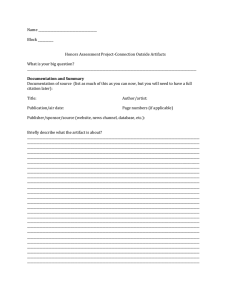

New Philadelphia Project Pedestrian Survey

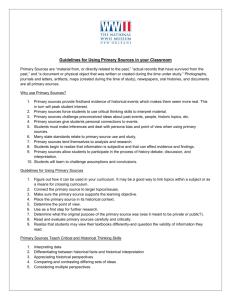

advertisement