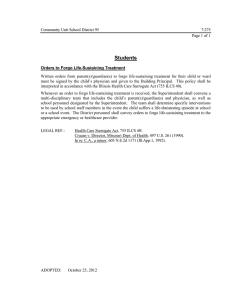

Withholding and Withdrawing Life

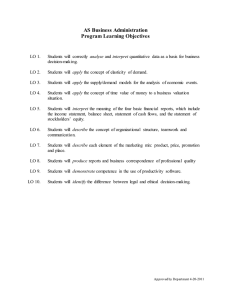

advertisement